Policy Papers

ON360 Transition Briefings 2022 – Ontario Needs a Broader and More Coordinated Approach to Innovation Policy

Higher levels of innovative activity drive growth in productivity. In particular, productivity growth is linked with higher pay and increased living standards for Ontarians. Yet productivity growth in Ontario has fallen steeply over recent decades, amidst a wider productivity slowdown across most advanced economies. There are three approaches that Ontario’s next government should take to boost the province’s innovative performance with these challenges in mind.

Overview

Measures to boost innovation—which is defined as new products or processes that add value to somebody’s life and improve economic or social well-being—have long been a focus of policy discussion in Ontario, and with good reason. Higher levels of innovative activity drive growth in productivity, which “in the long run is almost everything,” in the words of Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman. In particular, productivity growth is linked with higher pay and increased living standards for Ontarians.

Yet productivity growth in Ontario has fallen steeply over recent decades, amidst a wider productivity slowdown across most advanced economies. The future looks no better: economic growth in Ontario is projected to further slow in coming decades due to an aging labour force with falling participation rates.

Successive provincial governments have committed to boosting the level of innovative activity in Ontario, but the province’s businesses have continually under-innovated. In general, Canadian business has for decades been “only as innovative as it has needed to be.” Firms have decided that it makes more sense to acquire innovations from abroad rather than innovate themselves. Technology adoption is an important component of a holistic approach to boosting economic productivity. But it is concerning that businesses have depended on low wages, rather than innovation, to remain cost-competitive and earn above-average profits.

More worryingly, this “low-tech, low-innovation equilibrium” may no longer be sustainable due to pandemic pressures and technological changes that have shifted firms’ calculations of the costs and benefits of tech adoption. At the same time, economic growth is increasingly reliant on intangible capital technologies with very low marginal production costs, which makes it easier for one firm to dominate the global market. Ontario businesses therefore have to compete with the world-leading firms, rather than being able to simply adopt their technologies for the Canadian market. This increases the imperative for made-in-Ontario innovations.

There are three approaches that Ontario’s next government should take to boost the province’s innovative performance with these challenges in mind. First, it must take a multi-dimensional view of the barriers to innovation and a multi-pronged approach to policy solutions. This includes integrating areas traditionally seen as outside the domain of innovation policy, such as skills, immigration, and housing. Second, it must ensure that its policy actions build on—rather than duplicate, or ignore—the flurry of innovation policy activity at the federal level. Finally, the next government must place at least as much emphasis on the diffusion of innovations across all businesses in Ontario as it places on advancing the innovative frontier. Together, these approaches can help spur innovation and inclusive economic growth across the province.

Measures to improve the supply and demand for innovation in Ontario

Most discussions of innovation policy focus on ‘supply-side’ measures that aim to increase the amount of innovation occurring in a region through, for example, corporate subsidies or direct government grants. Efforts by the current Ontario government to boost innovation are largely characterized by a focus on providing incentives to spur business innovation and trade.

One crucial input to innovation is research and development (R&D) expenditures. Tax credits that subsize spending on R&D are one of the most popular supply-side tools, and are generally effective in stimulating R&D, especially in smaller firms with lower R&D spending. The generosity of these credits is higher in Canada than in the majority of developed economies, but Ontario offers the lowest levels of support among all provinces.

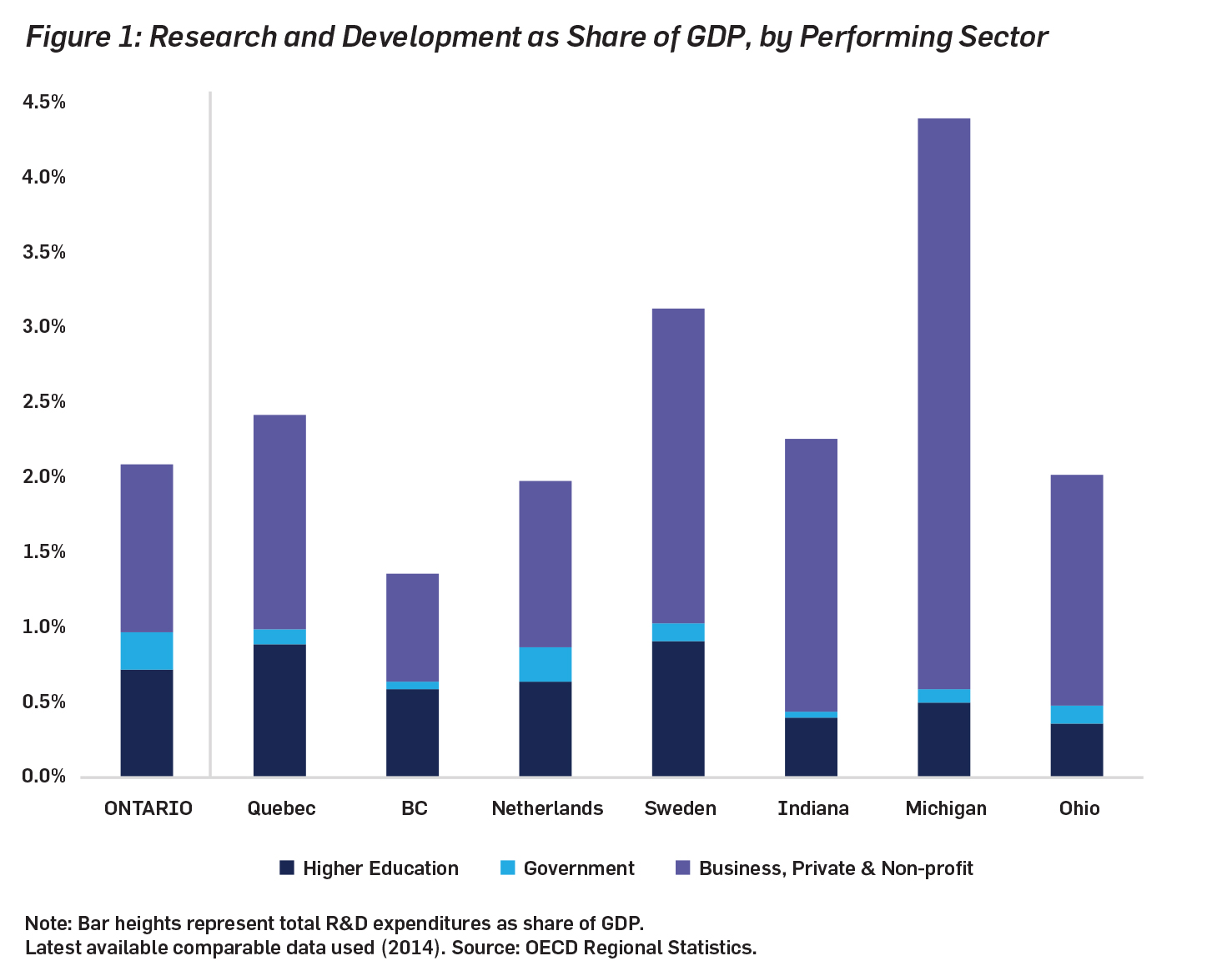

The following chart compares Ontario’s R&D spending to similar jurisdictions, broken out by the sector that actually performs the R&D work (so, for example, a university professor contracted by a firm would be categorized as ‘Higher Education’).[1] Ontario is middle-of-the-pack in terms of total R&D spending (as a share of GDP), but has generally lower levels of R&D performed by the business sector. Increasing the level of R&D performed by Ontario businesses therefore appears to be an important area for addressing shortfalls in overall R&D spending.

Another important input for innovation is the amount of financing available to Ontario businesses—particularly venture capital. This has historically been a constraint on the ability for high-growth Canadian companies to access capital and management support. Even in the late 2000s Ontario still lacked seed capital providers. Governments, including Ontario’s, responded by establishing public-private venture capital funds. Along with a booming tech sector that attracts funding from abroad, these efforts have substantially improved access to capital for Ontario businesses. Canada has recently enjoyed back to back record years of venture capital exits, and Ontario led among provinces in terms of VC deal volume. Despite these successes, there is still much room to grow. In the latest comparable data available (for 2020) Ontario had less VC investment than Utah or Minnesota—states with populations that are only one-fifth and one-third the size of Ontario’s (respectively).[2]

Intellectual property (IP) is also often centered in innovation policy discussions. This has been an area of past concern, related to Ontario’s underperformance in translating research strengths into commercial success. The Ontario government has responded with several recent moves to improve IP policy, including the first-ever provincial IP plan that focuses on commercialization of university research. This should help combat the longtime trend of patents invented in Ontario being owned abroad, who are then able to generate revenue from commercializing the patented ideas. But these recent efforts will take time to pay dividends.

These supply-side measures are well-established approaches in innovation policy, but have been viewed as insufficient for raising innovation and productivity to desired levels. More recent ideas, such as for a Canadian DARPA, are promising (if unproven). But efforts to raise the level of business innovation solely by increasing the supply of innovative ideas often resemble ‘pushing on a string’. Instead, many governments have begun emphasizing demand-side measures such as public procurement, consumer policies, and user-led initiatives that ‘pull’ innovation. These approaches reflect a re-conception of innovation from a linear view focused on R&D to a broader-based approach that considers the full scope of the innovation cycle.

Procurement is the most valuable demand-side measure to boost innovation. The government can leverage its buying power to boost economic growth, either by directly investing in Ontario businesses or by putting conditions on procurement that support investments in the province. It can act as an early adopter of innovations that exist but are not yet available on a large-scale commercial basis. These approaches can also be tailored to support environmental and equity, diversity, and inclusion priorities. However, the Ontario government has not yet replaced several procurement programs that were eliminated in recent years. Given that provincial governments are responsible for most procurement outside of defence, a new innovation procurement program—especially one related to small and medium-sized enterprises—would be an important contribution to boosting innovation in Ontario.

Other demand-side approaches are promising, but less certain. Challenge prizes are increasingly popular, and have been offered in Ontario—though lessons from history suggest that these must be carefully designed and are most effective when used to promote innovative “refinements, not revolutions”. Provincial regulations can be crafted to encourage new technologies to emerge, but governments must be careful of the costs that regulation can impose. One likely area of improvement is competition policy. Though mainly determined at the federal level, Ontario should do whatever it can to ensure that businesses face greater competitive pressures since this will drive them to innovate. In general, the Ontario government should look at all tools at its disposal to improve the province’s innovative performance.

Recommendations for an improved approach to innovation policy in Ontario

There are several actions that the next Ontario government can take to boost the level of innovative activity in the province. The previous discussion focuses on specific measures through which innovation policy can be improved. But there are also several high-level changes the next government should consider as to how it orients, combines, and structures its innovation policies in order to make them most effective.

1. Integrate other relevant factors into discussions of innovation policy

Innovation policy has tended to focus on supply-side measures, with demand-side policies receiving more recent attention. But Ontario needs to consider that a very broad range of government actions impact innovation.

Skills development policies, for example, are important for deploying and attracting workers to help businesses grow. These should go beyond STEM skills and focus on other areas of need, such as marketing and business. A skills-based approach to innovation is especially important for inclusive growth, since these programs help Ontarians navigate labour market disruptions and transition to the future of work.

Immigration policy is a related area important for improving Ontario’s innovation performance. University-educated immigrants to Canada are estimated to have a positive effect on innovation (as measured by patenting). However, this effect is much stronger for immigrants who work in jobs that utilize their training. It is therefore important that the government effectively integrate newcomers into the Ontario economy, in order to maximize the benefits to innovation.

At the same time, increases in immigration to Ontario need to be matched with increases in the supply of housing. Insufficient housing volumes can constrain innovation, for example by limiting Ontario’s attractiveness as a destination for talented workers and by using up capital that could instead be invested in firms and spent on R&D. Most of the policy levers for housing are at the provincial and municipal levels, and there are several actions available to a government determined to build more housing in Ontario.

2. Design provincial policies that complement federal government innovation policy

Most of the policy areas discussed above entail overlapping jurisdiction between Ontario and the federal government. These governments have recently collaborated on investments in childcare, high-speed internet, and several businesses. Yet at the policy level, provincial actions frequently duplicate, or entirely ignore innovation policy measures at the federal level. It is important for both orders of government to build on their recent collaborations to better coordinate on several other areas of innovation policy.

Skills, immigration, and housing are all areas of overlapping jurisdiction where greater coordination between the Ontario and federal governments could support innovation-enhancing outcomes. Procurement policies at the provincial level are often complicated by the need to adhere to rules set by the federal government in international trade agreements. IP faces similar challenges and should also be subject to greater coordination between the Ontario and federal governments, for example as related to the federal patent collective pilot.

There are other areas where the Ontario government could make investments that complement federal spending. For example, the Quebec government has co-invested in the federal Supercluster in that province, but the Ontario government has had limited involvement in the Advanced Manufacturing Supercluster. The recent federal budget announced investments in critical minerals that offer opportunities for involvement by an Ontario government eager to develop the Ring of Fire. While a series of one-off investment collaborations ensures more rapid action, it is also worth considering the creation of a new inter-governmental joint investment agency to develop a ‘grand strategy’ around co-investments.

3. Emphasize wider diffusion of innovations, not just advancing the innovative frontier

There is growing recognition globally that aggregate productivity challenges are due to a ‘long-tail’ of low-productivity firms with poor technological adoption practices. And while globally competitive ‘superstar’ firms drive innovation and productivity gains, they also increase inequality. Improving technological adoption across a larger number of businesses can therefore promote more inclusive innovation.

Policies to boost productivity in a given industry more or less follow one of two approaches. First, governments can invest in advancing the frontier by funding basic research and helping firms develop new world-leading technologies and business methods. An alternative approach is investing instead in the diffusion of existing innovations to all firms in the province (especially the ‘laggard firms’ least likely to adopt). While impacts may be more complex, policies typically lean towards either advancing the frontier or increasing diffusion. There are worthwhile questions of whether the allocation of investments between these should be 50-50, or 75-25, or some other split.

Diffusion is best accomplished with incremental innovations that enable firms to offer new products, streamline business processes, and reach new markets. It can be supported by ensuring that businesses are sufficiently aware of new technologies and have the skills to utilize them, can access capital, and have strong links with academia. There may also be technological barriers to surmount, such as ensuring that there is strong enough broadband for cloud-based systems to function effectively. In general, improving inter-firm linkages, for example through cluster development agencies, is important since cutting-edge technologies usually diffuse to laggard firms only after frontier firms adapt them to local contexts.

In Ontario, governments often emphasize the first, ‘frontier approach’, for example through efforts to grow the province’s artificial intelligence (AI) sector from a strong foundation of early world-leading research. While some policies that improve the diffusion of innovations do exist, such as skills development (especially management expertise) and IP pools, they deserve greater emphasis. The productivity gains of AI, for example, will be from widely applying these innovations to Ontario businesses, such as by increasing the efficiency of manufacturing processes, not from being home to the world’s best AI researchers. Moreover, the investments to widely diffuse these innovations—such as installing instrumentation and control systems that carefully track production processes, so that AI can be used to find efficiencies—will often require very different kinds of labour than is needed to develop these.

As the next government crafts innovation policies to boost economic growth over coming decades, it should be equally focused on actions that prioritize diffusion of innovations throughout all Ontario businesses and on promoting innovation by the leading-edge ‘frontier’ firms.

Jacob Greenspon is an economist (MA Queens) who is currently pursing a Masters in Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School of Government, with a specific interest in labour economics.