Policy Papers

ON360 Transition Briefings 2022 – Recent trends and long-term challenges in Ontario’s labour market

COVID-19 has had a substantial, unequal, and sustained impact on the Ontario labour market. As the province rebuilds, it is important both for economic and equity reasons that those who suffered most during COVID-19 are brought back into the labour force and employment. The Province can leverage tools, such as immigration policy and re-skilling of displaced workers, to ensure a robust labour force for strong and sustainable growth.

Overview

Although recovery is well under way, COVID-19 has had a substantial, unequal, and sustained impact on the Ontario labour market. Several long-term trends also limit the prospects for recovery, including population aging and declining labour force participation rates. These are cause for concern. As the province rebuilds from the pandemic, it is important both for economic and equity reasons that those who suffered most during COVID-19 are brought back into the labour force and employment. The Province can leverage other tools, such as immigration and re-skilling of displaced workers, to ensure a robust labour force for strong and sustainable growth.

Uneven economic impact of COVID-19 offers challenges and opportunities for recovery

While the Ontario economy is clearly still suffering from the effects of COVID-19, there are signs of a strong recovery. The unemployment rate in February was 5.5%, lower than in the year prior to the pandemic. This is a positive sign: After the Great Recession, the overall unemployment rate remained stubbornly high (above 7%) until 2015. Ontario’s employment rate, which also takes into account changes in labour force participation, only reached its 2011 level in 2019, before falling 3.7 percentage points during the first year of the pandemic.

Yet aggregate trends mask variation across the population. In most economies, the workers hardest hit by COVID-19 were those who were unable to work remotely, had other responsibilities at home (such as child care), or who already suffered worse labour market outcomes. Ontario was no exception. The Labour Force Survey data from Statistics Canada for February 2022 sheds light on the experience of different groups in the Ontario labour market.

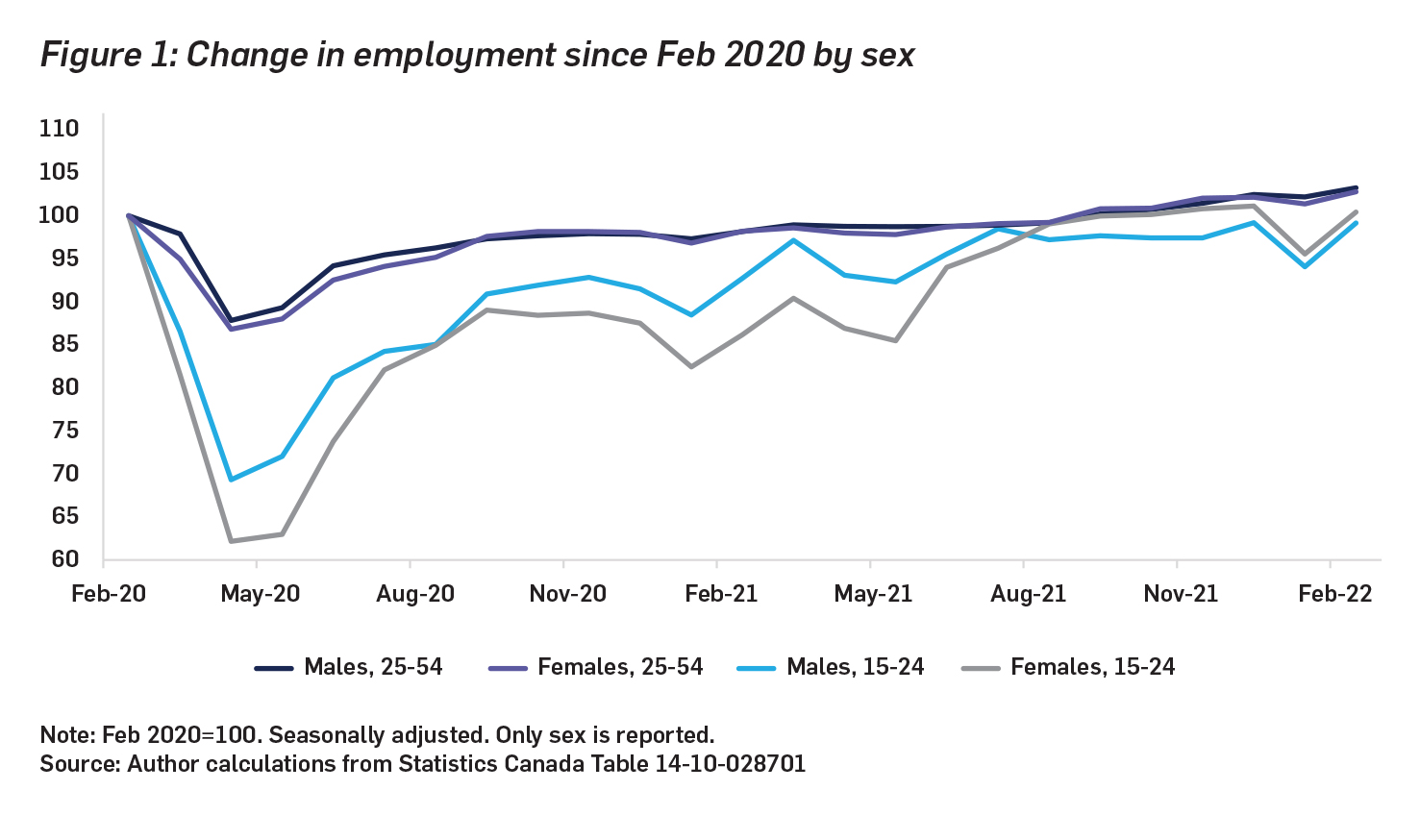

One well-documented unequal impact of the pandemic has been the ‘shecession’ in Ontario. Among the core working age population aged 25 to 54, the number of females employed fell by 13.2% from February to April 2020. It did not return to its pre-pandemic levels until September 2021, and lagged behind the recovery in male core working age employment for much of this period.

Some of these differences are due to family responsibilities. About half of Ontario’s working-age population is female, but they make up over three-quarters of those who want a job but do not search for one due to childcare or other family responsibilities. As well, two-thirds of Ontarians who report leaving their job in the previous year due to childcare or family responsibilities are female (and that excludes those who leave due to pregnancy). Challenges accessing childcare safely and affordably have a tangible impact on participation in the labour force. Among Ontarians aged 25 to 44 of both sexes, the participation rate is 1.6 percentage points lower for those with a child under age six. The share of these parents of young children that report being absent from work is nearly three times higher than for Ontarians without children aged six and under.

Among youth aged 15 to 24, the male-female employment gap during COVID-19 was even larger. In general, youth unemployment remained particularly high throughout this period and increased sharply during the pandemic. These trends are in line with high job losses in industries closed due to pandemic restrictions, such as food services and retail, which have high rates of youth employment (especially females). The unemployment rate for core-age and older workers had smaller increases, and have not decreased as much since.

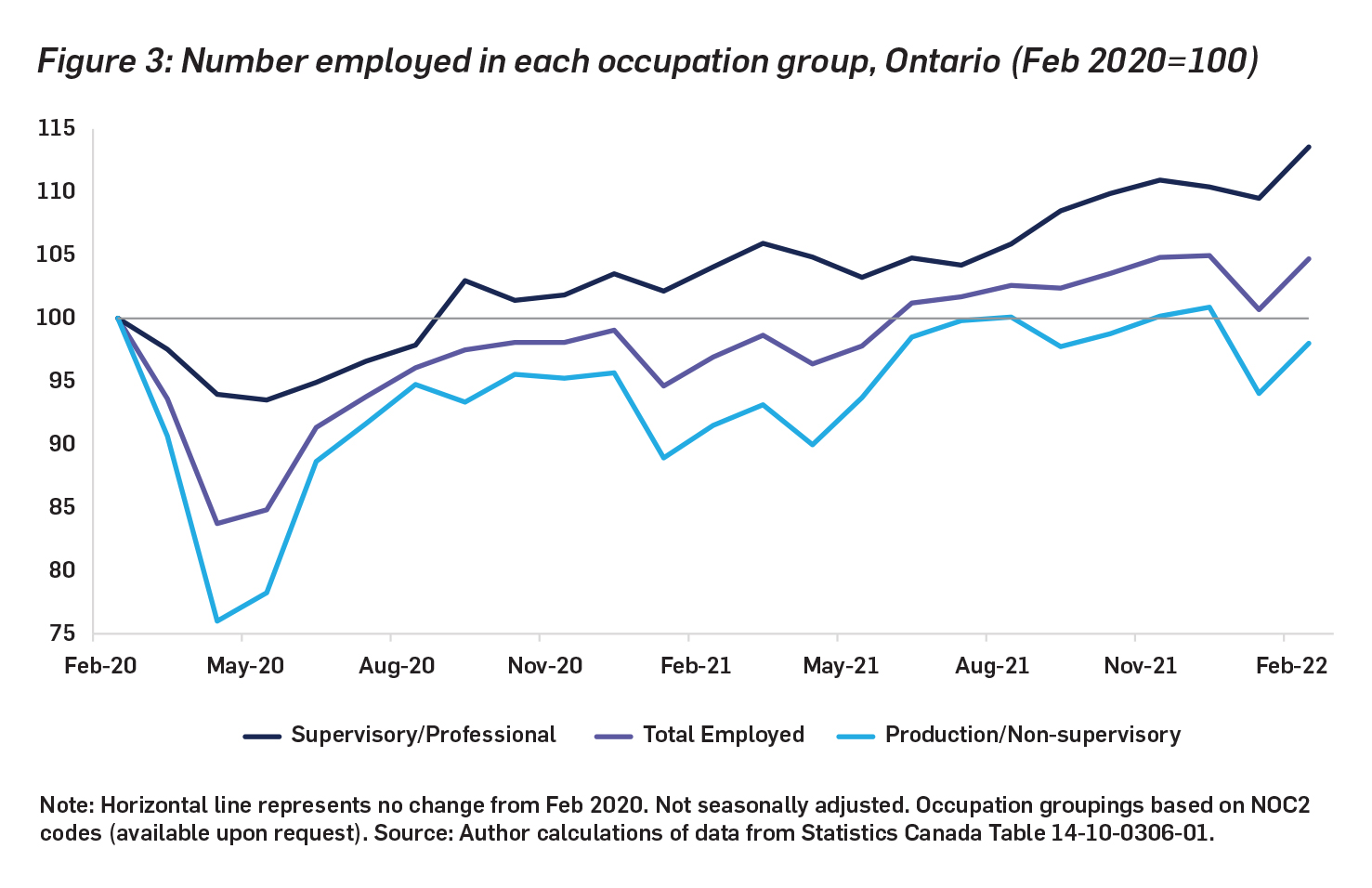

Another dimension of the unequal impact of COVID-19 is across different job types. During the first lockdown in spring 2020, employment fell the most for Ontario workers in production and non-supervisory occupations such as office support, care providers, sales representatives, and heavy equipment operators. Employment in this occupation group did not recover to its pre-pandemic level until July 2021, and then decreased again for most of the fall. Employment decreased far less, and recovered far more quickly, for Ontarians employed in supervisory and professional roles.

Ontario labour market is restructuring, but with little indication of overall worker shortages

COVID-19 has impacted each sector of the Ontario economy differently. The hospitality and retail industries had to close due to lockdowns and lay off staff as a result. Others, such as those related to the booming real estate sector, performed much better.

The chart below compares the most recent data on employment by sector in Ontario (from February 2022) to data from two years earlier, just before the pandemic arrived (looking at the same months also avoids the impact of seasonal patterns). This analysis reveals several shifts in the industry structure of employment in Ontario. Employment has increased the most in the finance and real estate sectors, as well as in construction and transportation and wholesale, which now employ about 1 in 12 Ontarians with a job. The largest decrease was in the agriculture and natural resources sectors (down 12% from start of pandemic), although this sector is only 1% of Ontario’s total workforce. The number of Ontarians employed in the industries most heavily restricted by lockdowns—food, hotels, and retail—is still three percentage points lower than at the start of the pandemic.

The uneven recovery across sectors of the economy is also related to concerns of labour shortages, which have received a great deal of attention in the United States. These are more difficult to measure in Canada at the provincial level, but one indicator is trends in real average hourly wages (that is, after adjusting for inflation). A shortage of workers would be expected to lead employers to raise offered wages in order to fill openings and prevent their employees from leaving for other work. However, after adjusting for inflation, there has been little average wage growth in Ontario since the start of the pandemic, both for workers overall and when calculating the average by occupational group. This suggests that employers have not yet felt the need to fill worker shortages by increasing wages beyond the rate of inflation.

Aging population and slow labour force growth may constrain economic recovery

According to the total-economy average wages data, there is likely still some slack in the labour market. Nonetheless, long-term trends suggest that there are challenges ahead.

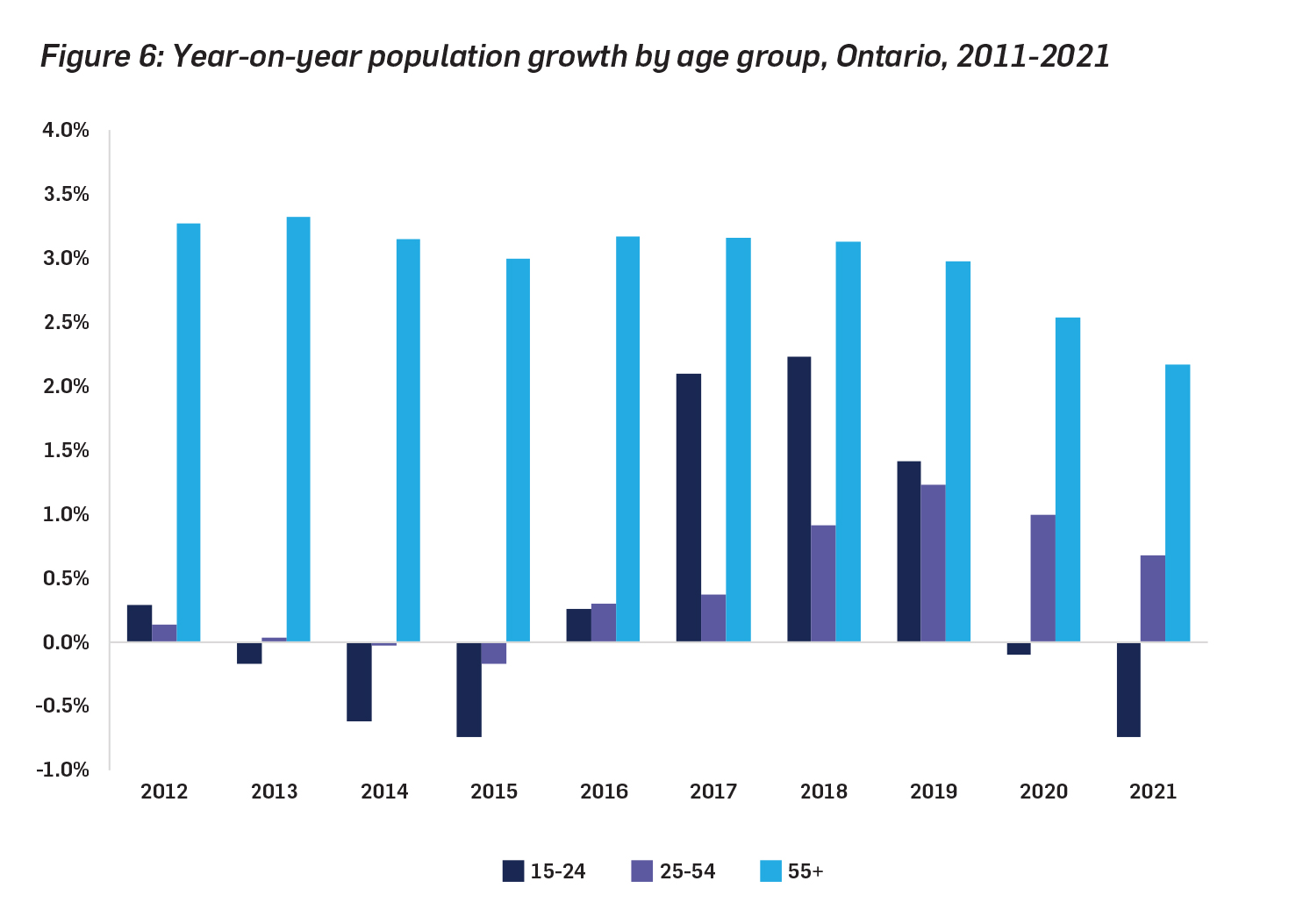

Ontario’s population grew at average annual rate of 1.3% over the past decade, but is aging rapidly: Between 2011 and 2021, the number of Ontarians aged 65 and older grew by 3.7% per year on average, over nine times the growth rates of the core working age (25 to 54 years) and youth (15 to 24 years) populations (0.4% per year for each). This population aging could constrain economic growth (for example, due to fewer potential workers) while the higher old-age dependency ratio strains provincial finances. In 2021, there were fewer than four working age Ontarians for every resident over age 65, whereas a decade ago the ratio was over five to one.

Increased participation of older Ontarians has not made up for decline in youth participation

An aging population also translates to slower labour force growth, which averaged 1.1% per year over the past decade and was particularly slow from 2011 to 2016 before accelerating in a tight pre-pandemic labour market.

The slow rate of labour force growth is in part because the share of Ontarians participating in the labour force has also decreased. The participation rate for all residents aged 15 and older declined from 66.5% in 2011 to 64.9% in 2021. This is not due to declines in the core-working age labour force participation rate, which has been relatively stable over this period. There have also been large increases in the participation of older workers, particularly those approaching (but not at) retirement age: Between 2011 and 2021, the labour force participation rate for Ontarians aged 60 to 64 years rose by 8.4 percentage points and increased for Ontarians 65 and older from 12.2% to 14.9%. These trends suggest that, even in the face of an aging population, there is some room to grow the labour force by supporting older Ontarians who want to continue working.

Much of the overall decrease is driven by the youth labour force participation rate, which even before COVID-19 had fallen from 62.3% in 2011 to 61.5% in 2019, and then fell an additional 1.2 percentage points by 2021. This declining participation has occurred among both sexes, but for youth aged 15 to 19 years the decrease has been driven by females while for youth aged 20 to 24 the fall was larger for males. Both are related to a decline in the part-time proportion of the employed.

Declining youth labour force participation is less concerning if they are in full-time education. The share of Ontario youth who are NEET (not in employment, education, or training) fell to 8.7% in February 2022, from 10.7% in February 2021. But this is still above the pre-pandemic NEET rate of 8.5% in February 2020. Ontario now has the second-highest NEET rate outside the Atlantic provinces, whereas it had the second-lowest in February 2020.

The next provincial government must take action to grow Ontario’s labour force

The provincial economy needs a strong and sizable labour force in order to grow. Long-term trends of population aging and falling labour force participation threaten the economic recovery from COVID-19.

There are several areas in which the next provincial government could take action to boost Ontario’s labour force. Additional workers could be hired from among those who have left the labour force due to job loss. This may be facilitated by expanded retraining and reskilling programs that help out-of-work Ontarians get hired into expanding sectors of the economy. Another potential source of labour force growth is youth, who have lost employment during COVID-19 and have generally left the labour force over the past decade, as well as older Ontarians who want to continue working. Ontario should also seek to attract more immigrants—especially highly-skilled workers— and to enact policies that help integrate immigrants into the workforce. Policy actions in these areas will be crucial to ensuring that Ontario continues to be a place to grow.

Jacob Greenspon is an economist (MA Queens) who is currently pursing a Masters in Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School of Government, with a specific interest in labour economics.