Policy Papers

Integrating Newcomers into Ontario’s Economy: A Strategy for Professionally Skilled Immigrant Success

Jon Medow and Ollie Sheldrick summarize best practices from across the country, aiming to improve credential recognition in regulated occupations.

Summary or Recommendations

- Ontario’s Office of the Fairness Commissioner should draw from best practices across the provinces and territories in order to improve credential recognition in the regulated occupations.

- The Government of Ontario should work with Ontario employment organizations serving professional immigrants to identify key priorities for federal advocacy, including improvements to federal pre-arrival and foreign credential recognition supports.

- Ontario should renew the Bridge Training program with a strategic human resource and workforce development lens, employing demand-led, sector-based strategies. Bridge Training should be managed separately from locally integrated employment services.

- The Government of Ontario should expand eligibility for its Bridge Training programs to include individuals on work permits, and advocate for the federal government to relax eligibility requirements for federal programs.

- The Government of Ontario should work with Ontario employment organizations serving professional immigrants to build mechanisms that overcome Canadian experience barriers and address credential recognition in unregulated occupations.

Introduction

Immigration is a vital contributor to both the scale and diversity of Ontario’s workforce. And it is only becoming more important. In 2014, in fact, the Ontario Ministry of Finance forecast that over the next 25 years immigration would account for all growth in the working-age population.[1] Put simply, Ontario needs immigrants to succeed. If we accept this view, then it is clear that the provincial government must deploy a range of policies to ensure that the skills and talents of newcomers are being utilized to the greatest possible extent.

Successive governments have sought to better integrate newcomers into the economy through a combination of intergovernmental arrangements, institutional reforms, and public policies. Important progress has been made. However, for many professionally skilled immigrants, significant barriers to full economic integration remain.

In this policy brief, we make the case that Ontario should develop a comprehensive strategy for the success of professionally skilled immigrants, leveraging the tools now centralized within the newly expanded Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development. The goal should be to better support integration of newcomers into Ontario’s labour market and maximize their human capital for themselves, their families, and the province’s economy.

The policy brief has three main sections. The first describes the evolution of the policy landscape in Ontario as it pertains to foreign credential recognition and the integration of newcomers into the labour market. The second analyses the growing importance of Ontario’s immigrant population in the labour market and its economy and how these trends are bound to continue. The third outlines a strategy to better integrate newcomers into the provincial economy and in so doing provide for greater opportunity for Ontario’s immigrant population.

Ontario Policy Landscape

Federal and provincial policymakers have been grappling with the question of how to better integrate newcomers into the economy since at least the 1980s. Much of this attention has been influenced by growing concerns (including academic scholarship) on the underperformance of immigrants in the labour market and the opportunity costs for them, their families, and the overall economy (calculated to be a loss of between $2-2.4 billion in a major 2005 study).[2]

This issue has transcended partisanship. Successive governments representing Liberal, New Democratic and the Progressive Conservative parties, have experimented with reforms to policies, institutions, and intergovernmental arrangements in the name of improving outcomes for newcomers to the Canadian economy. Examples include: the NDP government’s creation of the Access to Professions and Trades Unit in 1992[3]; the Progress Conservative government support for World Education Services in 2000[4]; a series of policy changes – including the Fair Access to Regulated Professions Act in 2006 (and later the Fair Access to Regulated Professions and Compulsory Trades Act) – under a Liberal government; [5] and the launch of new bilateral and pan-Canadian agreements at the intergovernmental level.

We start with this brief history because it is important to recognize that any strategy must engage with the panoply of current intergovernmental arrangements, institutions, and policies that underpin the pre-existing model for foreign credential recognition and the integration of newcomers into the labour market. The Ontario government is not starting from scratch. An effective strategy must build on the parts of the system that are currently working. To this end, it is worth drilling further into some of the key features and characteristics of the current system.

The Office of the Fairness Commissioner

The Fair Access to Regulated Professions and Compulsory Trades Act is the framework legislation that governs foreign credential recognition and training issues within set regulated occupations. It provides for a code of practice for the bodies that determine “entry to practice” in each regulated profession, reporting requirements, and an access centre for internationally trained individuals (Global Experience Ontario[6]), as well as sanctions for licensing and regulatory bodies that do not comply with the code. Oversight of these provisions is handled by the Office of the Fairness Commission (OFC), created as part of the Act.

The Office of the Fairness Commissioner has been led by three commissioners to date. The commissioner position was vacant from April 2019 to recently. The current government has just appointed a new person to this position.

As important as the Office of the Fairness Commissioner is, it is important to recognize that its purview is limited to regulated occupations in the provinces. Jobs in regulated occupations only make up approximately 20 percent of employment in Canada.[7] This means that the vast majority of jobs are not in regulated professions and not within the scope of the Office of the Fairness Commissioner.

The fact that a higher level of policy attention is placed on regulated professions may be explained by the fact that in those professions “entry to practice” is a tangible barrier. It is easy to understand when an individual is legally unable to work in their profession and clear which bodies are responsible for this issue. By contrast, in regard to unregulated occupations, lack of recognition of qualifications or experience often results from a lack of knowledge or from bias on the part of a potential employer, or from a lack of clear equivalency in the Canadian education system or labour market. These less-tangible factors may contribute to the lower level of policy attention that credential recognition in unregulated professions has received.

Few mechanisms are in place to ensure that credentials and experience are treated equitably for professional immigrants who work outside regulated sectors. This is of course a challenge not only for individual professionally skilled immigrants but also for the economy at large. Organizations such as World Education Services are available for immigrants to have their qualifications and credentials validated and equivalency established (for some immigration paths this is required for the application). Such validation is often key to the success of professionally skilled immigrants; however, broader supports and interventions are typically needed to build upon local validation.

Federal-Provincial Dynamics

Foreign credential recognition and the integration of immigrant into the economy are necessarily touched by intergovernmental factors given that immigration is an area of shared jurisdiction.

In 2001 the federal Immigration and Refugee Protection Act was passed, in part in recognition of anticipated labour shortages across Canada. This Act was the first of a number of policy developments over the last 18 years that have resulted in an increase both in the total number of immigrants arriving in Ontario and in the proportion of those arriving with professional credentials and experience.

The foundation of the partnership between the federal and Ontario governments on immigration is the Canada-Ontario Immigration Agreement (COIA). The first was signed in 2005 and provided $920 million in immigration funding over five years to support settlement and integration, as well as to help immigrants “achieve their full potential.”[8] New federal funding was directed toward provincial settlement services, with 30 percent destined for employment programs. COIA also led to the creation of the Ontario Immigrant Nominee Program (OINP), which allows Ontario to recommend to the federal government potential immigrants who meet the province’s labour market needs.

While Ontario’s capacity to fund employment-focused settlement services has increased with COIA, this is an area in which the federal government has maintained a strong focus as a direct funder of similar services. Other provinces, including Quebec, Manitoba and British Columbia, have had more robust devolution arrangements.[9]

Changes to Professional Immigrant Selection and Support

Pathways for professional newcomers to immigrate to the Province of Ontario have evolved over the past twenty years or so, as have the accompanying support mechanisms. The goal of these reforms has been to place a greater emphasis on labour market needs, skills, and the attraction and retention of professionally skilled immigrants in Canada. These include:

- The Post-Graduate Work Permit in 2007 to allow international students to stay in Canada and work up to three years after graduation[10];

- The Canadian Experience Class in 2008 to facilitate the transition of students or temporary workers to Permanent Residency if they succeeded in gaining professional work experience in Canada;

- The launch of a pilot program, called the Canadian Immigration Integration Program, a partnership between the federal government and local service providers offering pre-arrival services to newcomers. The pilot became a fully-fledged initiative, called Newcomers Success, in 2015[11];

- In 2015 the Express Entry immigration track was launched, with the intention of better aligning the inflow of immigrants with current labour market needs;

- That same year saw the introduction of Local Immigration Partnerships, a federal program creating multi-stakeholder partnerships positioned to coordinate outreach service delivery for immigrants after arrival; and

- New federal economic class pilot programs beginning 2012, including the 2019 Rural and Northern Pilot.

The COIA between the federal government and Ontario was last updated in 2017, keeping the current agreement in effect until 2022 and renewing commitments to federal-provincial collaboration in the Foreign Credential Recognition Program (FCRP) toward immigrant economic success.

Alongside the COIA between Ottawa and the province is the broader 2009 Pan-Canadian Framework for the Assessment and Recognition of Foreign Qualifications.[12] This non-legal public commitment made by all provinces and the federal government, developed by the Forum of Labour Market Ministers (FLMM), committed provinces, territories and the federal government to collaborate in the FCRP on the basis of principles of fairness, transparency, timeliness and consistency.

As a result of these changes, the immigrant selection landscape is now more varied and complex than it was pre-2001. Although the federal government remains the dominant player, the province (through the OINP), employers (through the Canadian Experience Class), and post-secondary institutions (through their admissions processes, as well as the Post-Graduation Work Permit) all now play a selection role in some capacity. Organizations and funding programs for employment-focused services for professionally skilled immigrants have also grown and matured. However, these supports have not always kept pace with innovations in selection processes, current trends, and most effective practices in linking employers with the skilled workers they need.

Shifting Responsibility for Settlement Services and Training

In 2018, with the folding of the Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration, its responsibilities were redistributed to other provincial ministries. Global Experience Ontario and Bridge Training were transferred to the Ministry of Training, Colleges, and Universities (MCTU), which had been the original home of Bridge Training. Bridge Training was placed under the umbrella of Employment Ontario, the province’s flagship suite of employment and training services for jobseekers and employers. Responsibility for the Office of the Fairness Commissioner was also transferred to MTCU.[13]

In October 2019, a further change occurred. Responsibility for all employment and training programming was transferred from MTCU to a newly expanded Ministry of Labour – the Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development (MLTSD).[14] MTCU was renamed the Ministry of Colleges and Universities. Bridge Training, the Office of the Fairness Commissioner, and Global Experience Ontario are all now housed within the new MLTSD.

Prior to this most recent ministerial reorganization, MTCU’s priority for the Employment Ontario system was to pilot a new approach to cross-government integration of employment programs through local employment service system managers, to be launched first in three pilot communities.[15] This plan will likely proceed, with integration at the local level of employment programs that are currently contracted separately by Employment Ontario, the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services (Ontario Disability Support Program), and Service Manager Municipalities (Ontario Works). This structure represents an acceleration and local reframing of the cross-ministerial Employment and Training Services Integration project of the previous government – an important effort, but one that will need monitoring for potential implications for specialized services focused on professionally skilled immigrants.

We outline these institutional and policy changes to give readers a sense of the evolution of the current policy landscape and how significantly it has changed in recent years. The movement of different programs, initiatives, and offices now seems to have settled. The hope, of course, is this organizational stability will provide policymakers the chance to evaluate what parts of the system are working, what require reform, and how to better align policies with the government’s broader economic and social goals.

A Growing and More Highly Skilled Immigrant Population

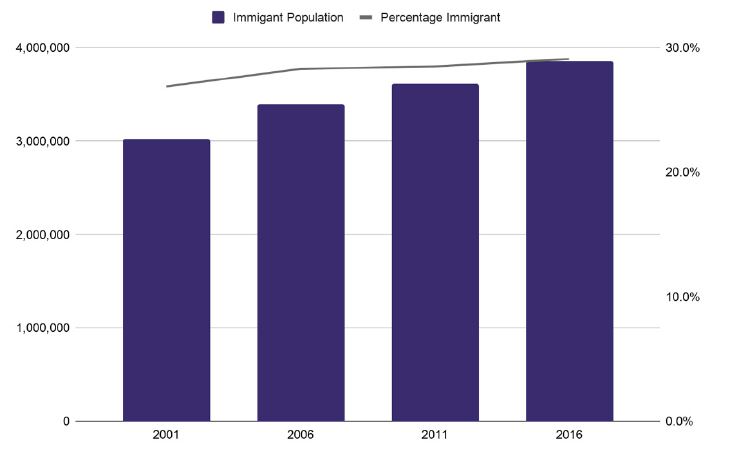

The policy developments outlined above have contributed to significant changes in the size of the immigrant population in Ontario. As seen in Figure 1, the total number of immigrants and the percentage of the population that they represent have grown significantly between 2001 and 2016.

Figure 1: Immigrant Population of Ontario: Size and Percentage, 2001–2016

Statistics Canada. 2017. Focus on Geography Series, 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-404-X2016001. Ottawa, Ontario. Data products, 2016 Census.

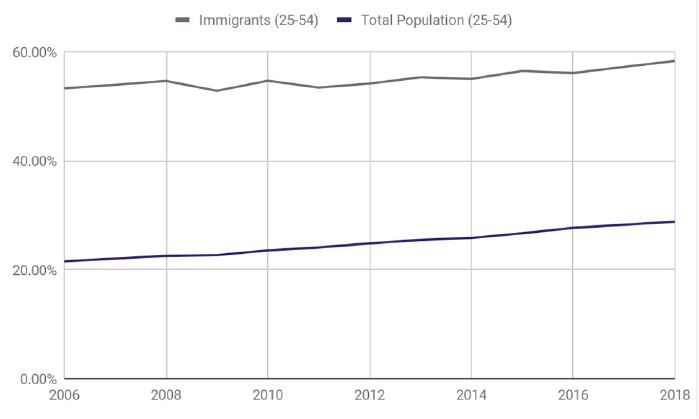

The educational profile of the immigrant population is also changing. At a national level, the proportion of working-age immigrants with Bachelor’s degrees or higher remains significantly above the national average and is showing a steady increase, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Percentage of working age (25–54) Immigrants, landed five years or less, with a Bachelor’s degree or higher and overall population, 2006–2018

Statistics Canada. Table 14-10-0087-01 Labour force characteristics of immigrants by educational attainment, annual (%).

Statistics Canada. Table 14-10-0118-01 Labour force characteristics by educational degree, annual (%).

Ontario and Canada are receiving greater numbers of increasingly well-educated immigrants. This has undeniably been an asset to Ontario. However, the changing nature of immigration also means that policy and programs must in turn adapt.

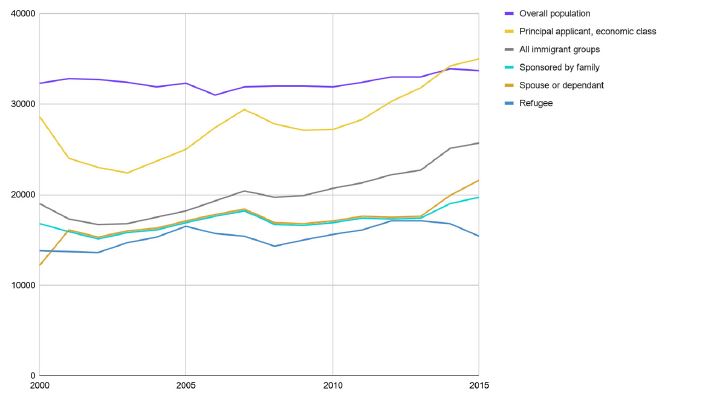

Economic performance for immigrants in the province has remained significantly below that of Canadian-born workers. As seen in Figure 3, for immigrants who are principal applicants in the economic class, the median income after a year in Canada is relatively strong, with the most recent data showing earnings exceeding the overall provincial median. However, this trend does not extend to immigrants as a whole, who earn significantly below the median (despite an above-average trend of salary growth over the last 15 years). Median incomes for spouses and dependents of immigrants and refugees continue to lag even further behind.

Additionally, while principal applicant economic immigrants out-earn the general population, it is important to contextualize this performance. The median salary of an individual with a Bachelor’s degree in Ontario stands at $85,645 for men and $70,832 for women.[16] Given that the majority of principal applicant economic immigrants coming to Canada have a Bachelor’s degree or above, or a recognized trades certification, they in fact have significantly lower earnings than Canadian-born peers with an equivalent education level.

Figure 3: Median incomes after one year of residence for immigrants to Ontario by immigrant class (by arrival year) and overall population median income, 2000–2015

Statistics Canada. Table: 43-10-0010-0. Immigrant Income by admission year and immigrant admission category, Canada and provinces.

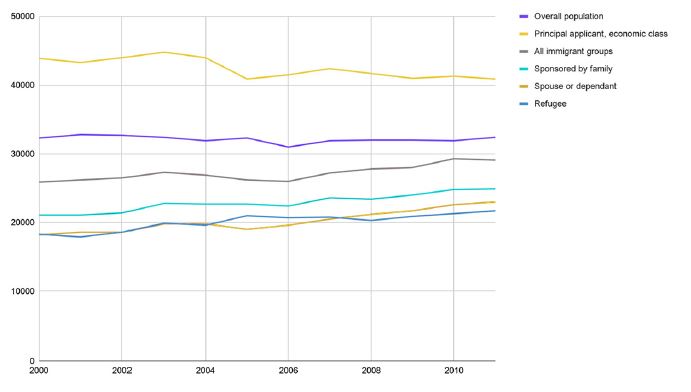

As immigrants further integrate into the economy, we see changes over time. After five years in Canada, principal applicants in the economic class have consistently greater earnings than the overall population, although, as seen in Figure 4, these are still lower than the earnings of Canadian-born workers with equivalent education levels. By contrast, after five years, immigrants overall still have earnings below the population median, and performance for refugees and spouses or dependents remains well below the median.

Figure 4: Median incomes after five years of residence for immigrants to Ontario by immigrant class (by arrival year) and overall population median income, 2000–2015

Statistics Canada. Table: 43-10-0010-0. Immigrant Income by admission year and immigrant admission category, Canada and provinces.

Between 2011 and 2016, principal applicants in the economic class made up only 20.8 percent of immigrants to Ontario; that is, nearly 80 percent of all immigrants still have earnings consistently below the population median. It is important to note that professionally skilled immigrants are not always principal economic applicants. A professionally skilled immigrant may arrive in Canada as a refugee, a spouse or a dependent of a principal applicant, or through family sponsorship. This means that there are many more professionally skilled immigrants with below-average earnings than would be reflected in principal economic applicant statistics alone – a larger population of new Ontarians whose skills are underutilized.

An Ontario Success Strategy for Professionally Skilled Immigrants

Ontario stands at an important policy crossroad. As the size and education level of the immigrant population continues to increase, overall economic success (as represented by median incomes) continues to lag. This gap between skills and outcomes represents an opportunity cost for the province’s economy and indeed for the individuals affected.

After significant movement in the last 1.5 years, Ontario’s key tools for advancing the success of professionally skilled immigrants are now centred in MLTSD, and the future of their use is currently unclear. Ontario has the opportunity to launch a success strategy for professionally skilled immigrants from within MLTSD, both advancing progress on this key file and demonstrating the capacity of the new ministry to leverage its employer relationships focused on labour matters, for new skills priorities.

Recommendation: Ontario’s Office of the Fairness Commissioner should draw from best practices across the provinces and territories in order to improve credential recognition in the regulated occupations.

Ontario is one of four provinces to have an Office of the Fairness Commissioner or equivalent.[17] Ontario was the first province in Canada to adopt this approach and has served as a model that others have followed.

Most recently, the United Conservative Party of Alberta laid out plans in a 2019 pre-election announcement to tackle the “doctors-driving-taxis” syndrome. Their plans pointed to Ontario’s policies as a starting point for developing Alberta-specific fairness legislation and an accompanying regulator. In June 2019, the Fair Registration Practices Act received Royal Assent in Alberta, enabling the government to establish a “Fair Registration Practices Office.”[18]

Now that a new commissioner has been appointed in Ontario, the key is to start to build on best practices in other provinces in order to make progress on credential recognition in the regulated occupations. The office’s track record is positive but there is certainly room for ongoing improvement.

Research by the first Fairness Commissioner using the National Household Survey and Census found a significant increase in the number of licenses awarded to internationally trained Ontarians between 2006 and 2011.[19] The percentage of immigrants who are licensed in the profession for which they are educated has moved closer to the percentage for Canadian-born peers. According to the reports from the Office of the Fairness Commissioner for 2017–18, there have been significant increases in the numbers of internationally trained professionals becoming licensed members of key Ontario regulatory bodies between 2012 and 2017.[20] Figure 5 highlights the professions with the largest increases.

Figure 5: Professions/trades with highest percentage (%) of increase internationally trained members, 2012–2017

Data reproduced from the Office of the Fairness Commissioner Annual Report 2017-2018.

The 2017–18 Fairness Commissioner’s report also pointed to improvements in reducing the Canadian Experience requirements of regulatory bodies for licensing and increasing compliance with FARPACTA.

In addition, it should be noted that licensing does not equal employment. Between 2006 and 2011 there was a 22.7 percent increase in the number of internationally educated license holders in Ontario, but at the same time, only an 11.5 percent increase in their rates of employment within their regulated professions.[21] While some good progress has been made on licensing, work is still needed on this front, in addition to a focus on bridging to employment itself.

A key strength of Canadian federalism is the provinces’ ability to learn from one another’s policy innovations. While Ontario created the concept of a “fairness commissioner,” other provinces have seen the value in this idea and made it their own. For example, one area that Manitoba’s fairness commissioner has emphasized is pushing regulatory bodies to expand reciprocity agreements with other countries. Some of the timeliest licensing outcomes have been achieved through such agreements.[22] Ontario should enter a period of renewal for the Office of the Fairness Commissioner, investigating how other provinces have iterated Ontario’s concept, bringing back new practices that can drive success.

Recommendation: The Government of Ontario should work with Ontario employment organizations serving professional immigrants to identify key priorities for federal advocacy, including improvements to federal pre-arrival and foreign credential recognition supports.

Many changes in Ontario policy and programming in recent years have been influenced by federal-to-provincial transfers of funding and responsibility. Still, the federal government continues to exert a broad measure of influence both in determining who immigrates to Ontario and in supporting the success of professionally skilled immigrants in the province. Ontario should advocate to the federal government on key priorities as part of a professionally skilled immigrant success strategy; this can include bilateral engagement as well as agenda setting at the Forum of Labour Market Ministers (FLMM).

A good example is the need for a better intergovernmental effort to promote greater awareness among immigrants about what will be required of them once they relocate to Ontario, especially – but not only – if they work in a regulated profession. Prior knowledge, and engagement either with the labour market or with appropriate regulatory bodies can significantly improve the new-arrival experience.

In Australia, the immigration process is designed to increase the transparency of labour market entrance; if prospective immigrants indicate that they plan to work in a regulated sector, they are required to engage with relevant regulatory bodies.[23] The federal skilled worker immigration stream in Canada now requires applicants to acquire equivalency assessments for their existing qualifications, but does not explicitly require engagement with regulatory bodies prior to arrival.

Although pre-arrival engagement is not current federal policy, the FLMM in 2014 included “pre-arrival commitment” in their Action Plan for Better Foreign Credential Recognition in their update to the 2009 Pan-Canadian Framework for the Assessment and Recognition of Foreign Qualifications. Pre-arrival commitment would ensure that prospective immigrants would receive a timely response from relevant regulatory bodies for their industry, along with an initial assessment of their qualifications and experience, as well as any further requirements.[24]

However, beyond the provision of information and engagement with regulatory bodies, which can certainly be improved, remote connection with specific job opportunities can substantially enhance arrival experiences. Direct supports for pre-arrival labour market engagement can also help employers to connect more quickly to needed talent. Such supports can also influence immigrants to locate in communities with available jobs, which they may not have been aware of or initially considered.

Pre-arrival services in Canada have undergone notable change in recent years. New pre-arrival pilot programs were launched in 2007, and some have become permanent.[25] In January 2019 increased funding was announced.[26] The most valuable pre-arrival programs are those that offer direct links to the labour market, providing opportunities to develop networks and the potential to secure a role before arriving in Canada.

Ontario, as the Canadian jurisdiction that receives the largest number of immigrants annually, should leverage the expertise of its leading employment organizations and settlement services to bring forward proposals to the federal government for further improvement to pre-arrival services that link directly to jobs, including the potential for more formal integration in federal immigrant selection processes.

The federal government also provides funding to provinces, territories and organizations to support foreign credential recognition through the Foreign Credential Recognition Program. Under this program, funding can be used not only to help assess credentials directly but also to more broadly advance the goals of the Pan-Canadian Framework for Assessment and Recognition of Foreign Qualifications. The program supports a wide range of interventions, including mentorships, loans to cover costs of pursuing foreign credential recognition, and even the pursuit of alternative employment while awaiting licensure. The Government of Ontario should similarly work with the sector to assess how well this program is meeting existing needs and bring forward recommendations to the federal government bilaterally, and potentially also within the FLMM.

MLTSD engagement with the sector to further develop key priorities for federal advocacy should form a foundation for an Ontario professional immigrant success strategy. This engagement can also serve as a vehicle for the new ministry to build its relationships with the sector.

Recommendation: Ontario should renew the Bridge Training program with a strategic human resource and workforce development lens, employing demand-led, sector-based strategies; Bridge Training should be managed separately from locally integrated employment services.

Ontario is currently undertaking a process of employment service integration within Employment Ontario. At the core of these changes is the creation of local service system managers, beginning in pilot communities, to deliver employment service programming currently funded by multiple Ontario ministries and municipalities. In addition, as of 2018, with the closure of the Ontario Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration, Bridge Training was moved to MTCU, and subsequently, in 2019, to MLTSD. Current delivery contracts with Bridge Training providers continue until 2021, when, if past patterns hold, providers will likely be selected for another round of multi-year contracts.

It is not known how MLTSD intends to manage Bridge Training in relation to wider employment service integration efforts launched by the former MTCU. The purpose behind the local integration of employment services is to combine the efforts of the many programs that predominantly serve populations in search of entry-level employment. Bridge Training, with its sector-specific and professional focus for skilled immigrants, is distinct. Further, rather than attempting an even distribution across the province, Bridge Training is concentrated in the common arrival destinations of Ontario immigrants. MLTSD should therefore continue to manage bridging training separately. The 2021 expiry of current Bridge Training contracts presents an opportunity for MLTSD to take a strategic approach to this specialized program stream, working alongside locally integrated employment services.

Traditionally, employment services and programs have been supply-oriented – that is, serving jobseekers – the goal being to support individuals in developing skills and characteristics that will help them succeed in entering or re-entering the labour market. Newer and more effective approaches begin instead with demand. They start by developing a detailed understanding of employers’ needs in specified occupations or sectors, developing relationships with employer human resource leads, and then providing all necessary training and support to help jobseeker clients effectively meet the needs expressed by employer partners.[27] The prior identification of employer requirements leads to the identification of opportunities for jobseeker clients. For this reason, demand-led approaches are often described as “dual-client approaches.”

Within this framework, organizations that facilitate linkages between jobseekers and employers, marshalling the resources required for the success of each, are sometimes called “labour market intermediaries.”[28] Such organizations blend jobseeker-facing training, capacity building, and wrap-around support referral capabilities with business-facing strategic human resources and talent development capabilities. Sector-focused mentorship for jobseekers is often a key component. Such demand-led strategies are common in the United States, where they have yielded “demonstrable benefits” for employers and employees.[29]

In recent years, a movement has emerged to implement such strategies in Ontario,[30] and some Bridge Training programs are currently modelled in this way. Since 2017, the former MTCU has been locally piloting a sector strategy approach through SkillsAdvance Ontario,[31] and a recent Ontario 360 policy paper by Karen Myers, Kelly Pasolli and Simon Harding has argued for a broader reframing of Ontario’s employment training system around demand-led approaches.[32]

In 2017 new Bridge Training pilot streams were opened: “Getting a License and Getting a Job”; “Changing the System”; and “Francophone Bilingual Employment.”[33] In total, 68 programs were funded, at an annual investment of $23.2 million. A 2017 Auditor General’s value-for-money audit of Settlement and Integration Services for Newcomers found that, while many Bridge Training programs reported good results, the then Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration was not making funding decisions effectively on the basis of measured outcomes, total funding for Bridge Training had declined, and coordination with the federal government needed to increase.[34]

In the next round of Bridge Training support, MLTSD has an opportunity to prioritize the long-term funding of organizations capable of functioning as sector-focused intermediaries and delivering demand-led programming that reaches the broad range of professionally skilled immigrants. This approach can leverage learnings out of the history of Bridge Training delivery and the most recent pilots, as well as nearly three years of former MTCU funding for SkillsAdvance. Similarly, focus on licensure in regulated professions should be maintained in the program, and emphasis on credential validation and recognition for non-regulated professions should be enhanced.

As local integration for the broader array of employment services proceeds, it is important that MLTSD focus on potential implications for Bridge Training deliverers who are also Employment Ontario service providers. In managing Bridge Training centrally, MLTSD must maintain dialogue with managers of local service systems to ensure that viability and effectiveness of Bridge Training programming is not undermined by local Employment Ontario funding decisions, as providers of Bridge Training may be reliant on Employment Ontario for core operational funding.

A renewed approach to Bridge Training could also include a regional development angle. In recent years, critics have highlighted the low number of provincial nominees that Ontario receives in comparison to other provinces.[35] One area where an increase in OINP-driven immigration could be particularly beneficial, as Charles Cirtwell has argued in a recent Ontario 360 article, is in attracting immigrants to Northern communities that face challenges of declining working-age populations and specific labour market gaps.[36] This is one of many calls for a regional immigration strategy that would attract immigration outside of the GTA.[37] Indeed, since Cirtwell’s article was published, the federal government has announced a new immigration pilot for Northern Ontario communities.[38] Bridge Training programs targeting specific Northern industries and geographies could provide a vital support for the success of efforts to attract immigrants to the North.

Recommendation: The Government of Ontario should expand eligibility for its Bridge Training programs to include individuals on work permits, and advocate for the federal government to relax eligibility requirements for federal programs.

In recent years the Canadian government has introduced a number of policies aimed at attracting (and retaining) potential immigrants already in Canada who, by virtue of their Canadian post-secondary education and work experience, may face fewer labour market barriers. These measures include the Post-Graduate Work Permit and the Canadian Experience Class, which target international students and individuals on work permits (including graduated international students).

Despite the shift in immigrant selection methods, many individuals that Canada is targeting as potential immigrants are barred from accessing key services that can support their economic success and thereby assist their qualification for permanent immigration.[39]

The federal and provincial governments both fund bridging programs. Provincial programs are open to citizens, permanent residents, convention refugees, and refugee claimants who have valid work permits. Federal programs have more limited eligibility. They are only open to permanent residents and convention refugees. Neither government provides access to bridge training for individuals on work permits who can qualify for permanent residence by obtaining professional work experience. This is counter-productive for talent retention.

In addition, as noted, federal bridging programs are not available to people who are already citizens. This is a problem because many professionally skilled immigrants who are dependents of principal applicants (and often women) may not begin their professional career journey in Canada until years after immigrating and becoming citizens. When we examine immigrant median income by gender five years after arrival, a significant disparity of outcomes is apparent even for principal economic immigrants (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Median incomes after five years of residence for immigrants to Ontario by immigrant class (by arrival year), gender and overall population median income, 2000–2015.

Statistics Canada. Table: 43-10-0010-0. Immigrant Income by admission year and immigrant admission category, Canada and provinces.

Statistics Canada. Table: 43-10-0010-0. Immigrant Income by admission year and immigrant admission category, Canada and provinces.

Research by the Canadian government into the experiences of immigrants has highlighted the value of having a family support network; many immigrants note that they would not be able to work as many hours, or at the level that they do without childcare provided by family members. This research also shows that dependents of primary applicants often do not work.[40] In recent years the federal government has focused on engaging more women in the labour market and reducing wage disparities.[41]

Recommendations to open up federal eligibility criteria for employment supports stretch back at least a decade.[42] The inclusion of citizens and an expanded time horizon for access to bridging services could be particularly beneficial to women. While opening its criteria for bridge training eligibility to include individuals on work permits, the current Ontario government should also reactivate this federal discussion around expanded eligibility.

Recommendation: The Government of Ontario should work with Ontario employment organizations serving professional immigrants to build mechanisms that overcome Canadian experience barriers and address credential recognition in unregulated occupations.

While many of the recommendations in this paper focus on specific programmatic changes, the barriers that professionally skilled immigrants face in the labour market are often broad and systemic in nature, and change is not easily brought about by discrete programs. Under the aegis of MLTSD, Ontario can play a positive role in supporting broader employer and labour market cultural change.

We have emphasized the importance of Bridge Training programs taking on the characteristics of labour market intermediary organizations. Such programs, through their engagement with and service to employers, have had success in building trust, increasing knowledge of the quality and comparability of professionally skilled immigrant talent, and reducing bias in hiring practices. However, in order to effect change, more macro-level interventions are needed, in particular, a focus on issues of Canadian experience requirements and credential recognition in unregulated occupations.

Canadian experience requirements have been a recognized issue for immigrants in Canada and Ontario for some time. Surveys of employers from 1983 highlighted that employers put “little value, or no value whatever, on work experience gained outside Canada.”[43] Canadian experience requirements predominantly affect professionally skilled workers rather than those looking for lower wage roles: “In occupations that are not highly desired by Canadian-born residents, the requirement of Canadian Experience usually does not exist.”[44] Reitz (2012) correspondingly found that lower-skilled immigrants actually have an easier time finding employment, at least initially.[45]

The Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) issued guidelines in 2013 stating that hiring requirements for Canadian experience raised human rights concerns in relation to immigrants and, for that reason as well, should not be used.[46] Employers who are adept in securing the best available talent also know that Canadian experience requirements are counterproductive.

The issue of requirements for Canadian experience has in recent decades been extensively covered in the media and in a number of papers, articles and reports.[47] Despite this increased recognition, the issue is still ongoing. In a 2018 report, the Toronto Region Immigrant Employment Council (TRIEC) named Canadian experience as one of the key barriers to employment for professionally skilled immigrants.

Immigrants seeking foreign credential recognition in unregulated professions face obstacles that result from a similar set of difficulties as Canadian experience barriers. Unlike with regulated industries, however, for which entry-to-practice barriers are predominantly clear legal issues, in unregulated sectors the obstacles arise from less tangible factors. In addition to a lack of awareness of the comparability of credentials and experience, these obstacles include racial bias and a broader “fear of the unknown.” Evidence suggests that a lack of awareness of credential equivalency services, discrimination against credentials from international post-secondary institutions, and the historically fractured nature of qualifications in Canada itself all play a part as well.[48] For these reasons, any legislative or policy response must be accompanied by broader cultural change.

The Ontario government should consult with professional immigrant-serving employment organizations that have had success in shaping employers’ hiring practices in relation to what innovative and culture-shifting practices could look like.

In recent years the Ontario Government has run successful publicity campaigns aimed at societal change on issues as diverse as sexual violence and youth concussion awareness. A similar approach, paired with direct outreach and enforcement of relevant laws and standards that utilize the full capacity of the new MLTSD to effect employer change, could potentially be taken to share information about the strength and depth of the immigrant talent pool in Ontario, the value of international qualifications and experience, and the advantages of a much higher level of reciprocity than may be currently appreciated in the labour market.

Conclusion

Breaking down barriers to the success of professionally skilled immigrants in Ontario is key to the future prosperity of the province. This challenge is not unique to Canada or Ontario. Other jurisdictions similarly are struggling to better integrate newcomers into their economies. If Ontario can get this right, it will not just be a boon to its economy and a comparative advantage, it will help to produce greater opportunity for immigrants in our province.

The last 1.5 years have seen considerable institutional changes on this file. The policies, initiatives, and offices related to foreign credential recognition and professional immigrant success have been moved between three ministries, with the Fairness Commissioner post vacant until recently. The conditions seem to have stabilized as evidenced by the recent appointment of a new Fairness Commissioner.

In this policy brief we have argued that Ontario should develop a strategy for professionally skilled immigrant success that leverages Bridge Training, the Office of the Fairness Commissioner, and the province’s capacities for cultural leadership and federal advocacy. Through such a strategy, Ontario can move the needle on an issue of key importance to the province’s prosperity while demonstrating the ability of its newly integrated labour and skills ministry to combine diverse resources and expertise to bring about change.

Jon Medow is Founding Principal of Medow Consulting, a Toronto-based consultancy building forward-looking solutions focused on skills, human capital and economic opportunity. Prior to launching Medow Consulting in 2017, Jon held civil service and political roles with the Ontario Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities in the Minister’s Office, Deputy Minister’s Office, and Indigenous Education Branch. Before joining government, he held policy, research, and government relations roles with Higher Education Strategy Associates, the Ontario Non-Profit Housing Association, and the Mowat Centre, where he served as Project Lead for the Employment Insurance Task Force. Most recently, through Medow Consulting, Jon has led research and strategy initiatives for clients that include the City of Toronto, United Way of Greater Toronto, Collège Nordique Francophone, and the Assembly of First Nations.

Ollie Sheldrick is a Senior Research Associate with Medow Consulting. Ollie is a senior policy analyst, researcher and writer with expertise in the areas of technology literacy and skills, social innovation, and the impact of technology on society. He has eight years’ experience in delivering high-impact research projects and policy analysis, ranging from nationally representative surveys to small-scale ethnographic studies and national policy analysis. Ollie has held previous research roles with the Ryerson Leadership Lab, and the Brookfield Institute for Innovation + Entrepreneurship. Prior to his move to Canada, Ollie served as Research Lead for Doteveryone, a UK-based think tank championing responsible technology, and spent two years as Policy & Research Manager for Go ON UK, a charity focused on adult digital literacy.