Policy Papers

ON360 Transition Briefings – It’s Time To Build: Liberalizing Ontario’s Land Use Rules To Boost Market-Rate Housing Supply

Ontario is facing a housing crisis – homes are too expensive and too scarce. Chris Spoke discusses the challenges and potential solutions.

Issue

Housing in Ontario is scarce and expensive, and becoming more so every year. This problem is especially acute in the province’s most productive regions. The government elected in June faces decisions on how to best tackle this problem, including on how to best act on the recommendations made by the recent Housing Affordability Task Force.

Overview: housing in Ontario

A problem of cost

The average price for a home in Ontario is now approximately one million dollars. In Toronto, the province’s largest city and employment center, it’s $1.3-million. And that’s across all housing types, including condominium units.

This high and rising cost of housing is of primary concern to many Ontarians, including young, middle class, and immigrant families who see the dream of homeownership moving farther and farther away.

The high and rising cost of housing in the province’s most productive regions in particular acts as a barrier to access and contributes to urban sprawl, long commutes, and traffic congestion (and their associated environmental impacts), as people are forced to live farther and farther away from their places of employment.

A problem of scarcity

Housing in Ontario is expensive because there’s not enough of it. This is especially true in the province’s most productive regions.

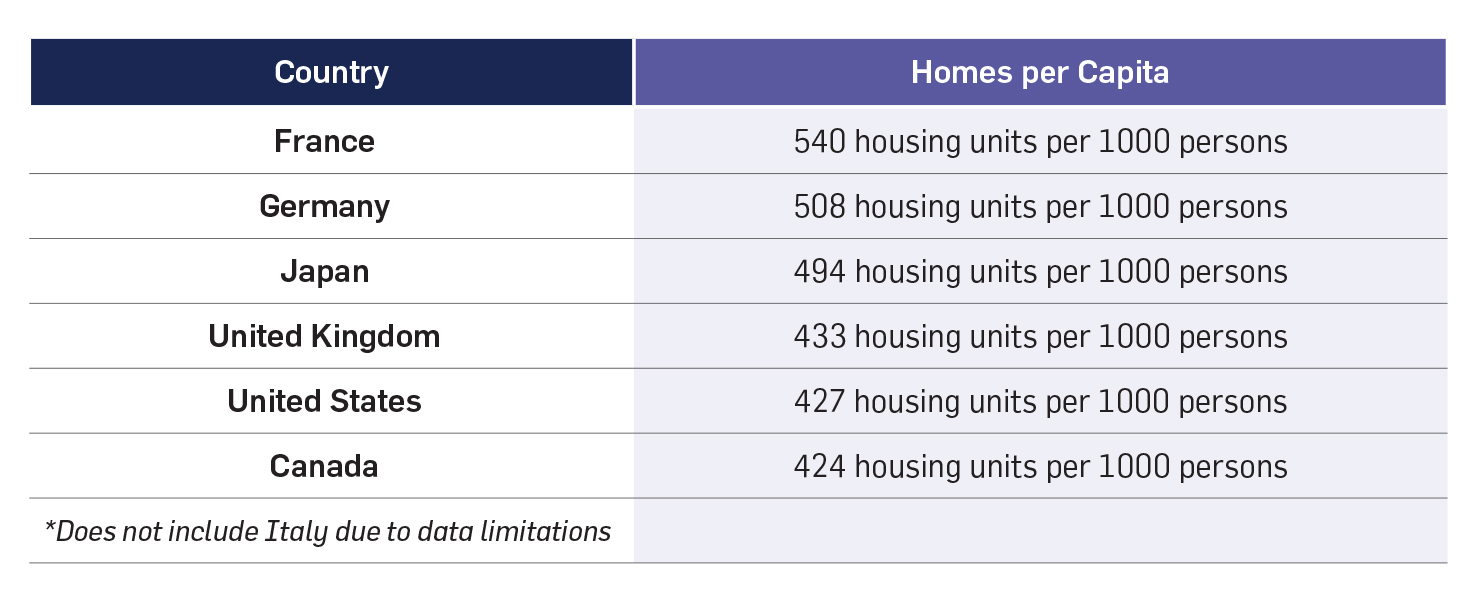

A recent Scotiabank Economics demonstrated that Canada has the fewest homes per capita of any G7 country, and that Ontario is tied with Alberta for the fewest homes per capita of any Canadian province.

This scarcity of housing has led to tremendous upward pressure on prices that could only be remedied by a policy of abundance.

Put simply: if we want more people to have housing in Ontario’s high productivity regions, we’re going to need to build more housing in Ontario’s high productivity regions.

Economist Mike Moffatt at the Smart Prosperity Institute has estimated that we will need to see at least one million new housing units completed over the next ten years to keep pace with new household formation. For context, we’ve seen approximately 670,000 housing completions over the last ten years from Q1 2012 to Q4 2021.

The Housing Affordability Task Force, for its part, has recommended that the Province establish a goal of 1.5-million housing completions over the next ten years, which would bring Ontario closer in line (depending on relative population growth over that time period) with the G7 average number of homes per capita.

A problem of local control

The primary constraints to scaling up new housing development lie in the world of municipal land use rules. These include limits placed on new housing development projects, regulating their type, height, size, form, and more.

For example, Toronto’s largest residential zone is the Residential Detached (RD) Zone, which only allows for detached houses, the lowest density housing type. In Ottawa, it’s the R1 – Residential First Density Zone.

These land use rules enjoy the broad support of many existing homeowners as they establish and reinforce a status quo often framed as “neighbourhood character preservation” in opposition to new development.

This political dynamic has come to be known as NIMBYism.

If municipal land use rules are to be reformed and liberalized to meet provincial housing completion targets, it will require a weakening of local municipal control over land use planning.

The need for reform

The high and rising cost of housing demands a strong policy response. The response will need to be framed around a weakening of local control over land use planning and housing development.

Given the local nature of housing development, a local example is instructive in highlighting the ways in which land use rules make even gentle intensification – that is, of a modest height and density – challenging.

A local example

I’ve listed below some of the specific obstacles faced by developers looking to build four-storey multi-unit buildings in Toronto.

This housing type and scale is generally referred to as the “missing middle”, a reference to the fact that their development has become uncommon since the introduction of increasingly prescriptive (and restrictive) zoning rules across North America in the 1960s and 1970s.

- Within Toronto’s Neighbourhoods land use area, which covers over 60% of the city’s land area (excluding roads, utility corridors, parks, natural areas, and other open space areas), the Official Plan requires that all new development:

“…respect and reinforce the existing physical character of each geographic neighbourhood, including particular:

- Patterns of streets, blocks and lanes, parks and public building sites;

- Prevailing size and configuration of lots;

- Prevailing heights, massing, scale, density and dwelling type of nearby residential properties;

- Prevailing building type(s);

- Prevailing location, design and elevations relative to the grade of driveways

and garages; - Prevailing setbacks of buildings from the street or streets;

- Prevailing patterns of rear and side yard setbacks and landscaped open space;

- Continuation of special landscape or built-form features that contribute to the unique physical character of the geographic neighbourhood; and

- Conservation of heritage buildings, structures and landscapes.”

- Within the Neighbourhoods land use area, multi-unit buildings (including duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, and four-storey apartment buildings) are only permitted in the Residential (R) and Residential Multiple Dwelling (RM) Zones.

They are not permitted in the Residential Detached (RD) or Residential Semi-Detached (RS) Zones which, combined, make up almost 70% of the Neighbourhoods land use area. - Within those Residential (R) and Residential Multi Dwelling (RM) Zones, multi-unit buildings are subject to a variety of criteria to guide their height, size, form and location on a lot. These include height maximums, depth maximums, as well as front, side, and rear setback minimums.

- Within these criteria, multi-unit buildings must, furthermore, not exceed permitted densities, which are set as a maximum Floor Space Index (Index) that quantifies the building’s floor area divided by the overall lot area.

More housing = more affordable housing

Again, housing in Ontario is expensive because there’s not enough of it. In order to place downward pressure on prices, the development industry will need to build much more of it over the next ten years.

The politics of this straightforward solution to a straightforward problem are complicated by the fact that broad-based housing affordability is achieved through increased supply despite new housing being generally more expensive than old or existing housing.

In fact, opposition to new housing development is often framed as opposition to luxury housing that will worsen the affordability crisis.

But a vast and growing empirical literature is emerging to further support the assertion that building more housing improves access to housing (ie, affordability).

How to move forward

The next Ontario government should implement all 55 of the recommendations made by the Housing Affordability Task Force, including the overarching goal to facilitate 1.5 million housing completions over the next ten years.

The following points repeat some of these recommendations, and introduce a few new ones, with a particular focus on removing barriers to the development of missing middle housing.

Though not nearly sufficient to achieve the goal of 1.5 million housing completions on their own, this housing type has the added benefit of distributing development more broadly beyond high-density nodes, exhausting local opposition through sheer volume, and drawing from a broader and more accessible talent pool for development and construction.

Near-term

- Set provincial standards requiring that all municipalities update their official plans and zoning bylaws to repeal or override all policies that prioritize the preservation of the physical character of their neighbourhoods.

- Set provincial standards requiring that all municipalities update their official plans and zoning bylaws to allow for a minimum of four residential units on all residential lots.

- Set provincial standards requiring that municipalities update their official plans and zoning bylaws to not include any maximum height lower than 12 meters.

- Set provincial standards requiring that municipalities update their official plans and zoning bylaws to end the practice of limiting permitted densities through a Floor Space Index (FSI) constraint.

Longer-term

- Create a zoning atlas digitizing, cataloguing, and visualizing all municipal official plans and zoning bylaws, including all maps, for maximum legibility and to facilitate province-wide analysis and cross-jurisdictional comparisons.

- Host annual expert reviews of municipal official plans and zoning bylaws, as well as the Ontario Building Code, with the explicit mandate and goal of reducing the scale and scope of these documents. The current political and bureaucratic incentives push toward continued increases in the scale and scope of these documents. A counteracting practice is required.

Chris Spoke is a real estate investor and the founder and CEO of August, a Toronto-based digital agency.