Policy Papers

ON360 Transition Briefings 2022 – Protecting Canada’s Plate: Building Resilience to Climate Change in the Agricultural Sector

Climate change will introduce high levels of uncertainty in agriculture and impact the production of food. Government action is needed to prepare for this inevitable threat. This policy paper presents ways to tackle this challenge and build resilience to climate change in agriculture.

This Ontario 360 policy brief was selected by faculty as the most outstanding paper of the 2022 Capstone course in the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy’s Master of Public Policy program. The honour was announced at the MPP convocation earlier this month. Ontario 360 is honoured to publish this paper.

Introduction

Agriculture is important. First, and most obviously, it provides food for Canadians. Expenditures on food account for the second largest share of household spending in Canada, second only to shelter costs (AAFC 2021f). Second, agriculture is a significant contributor to Canada’s economy. In 2020, agriculture employed 2.1 million people, provided roughly one in nine jobs across the country, and generated just over 7% of Canada’s GDP (AAFC 2021f). Third, agriculture plays an important role in Canadian foreign policy. Agriculture is one of Canada’s strongest foreign policy tools and an industry through which Canada makes its largest global impact. Canada was the fifth-largest exporter of agri-food in 2020, exporting to over 200 countries. Agriculture is therefore deeply linked to Canada’s international trade and geopolitical relationships with trading partners such as the U.S. and China (AAFC 2020b). Agriculture is particularly central to Canada-China relations; exports from Canada to China have increased by 72% since 2012 and continue to grow rapidly (AAFC 2021f).

Climate change is impacting how Canada grows food. Climate change will introduce high levels of uncertainty in agriculture and impact the production of food through an increase in temperatures, fluctuation in precipitation levels, and an increased risk of extreme weather events (Mbow, Rosenzweig, et al. 2019). Canadians are already witnessing these impacts; in 2021, farmers across the country sustained millions of dollars of damage due to unprecedented droughts across the Prairies, flooding in British Columbia, and wildfires on the West Coast and across Northern Ontario (Gomez 2021; AP 2021; Lipski 2021). Government action is needed to prepare for this inevitable threat; this capstone project seeks to recommend just that. The three proposals outlined in this policy agenda – ADAPT, LEARN, and INNOVATE – present ways to tackle this challenge and build resilience to climate change in agriculture.

Protect Your Plate, Canada

This proposal is focused on the issue of food security. Canada’s agricultural sector is currently unprepared for the impacts of climate change – keeping with the status quo, so to speak, will result in significant financial and social losses as every aspect of the food supply chain is disrupted. Now is the time to prepare for this future threat. This proposal calls on the nation: Protect Your Plate, Canada! The three options included in this policy agenda aim to secure a safe and stable supply of food for Canadians. They aim to protect the plates of Canadians now and forevermore.

The Protect Your Plate initiative is composed of three options: ADAPT, LEARN, and INNOVATE. The ADAPT proposal incentivizes the implementation of adaptive and climate-smart farming practices on agricultural operations. The LEARN proposal seeks to improve knowledge and awareness of ways to build resilience to climate change in agriculture. Finally, the INNOVATE proposal creates a regulatory sandbox to inspire innovations in agriculture. Each of these three proposals champion transformation and seek to inject innovation into agriculture. They attempt to harness the potential of agriculture, and to transform it into a solution to Canada’s climate problems as opposed to a major contributor. This paper will detail the proposed designs, instrument choices, governance, costing and implementation of the ADAPT, LEARN, and INNOVATE proposals.

First, however, a word on narrative. The Protect Your Plate narrative is critical to the success and public acceptance of this policy agenda. It reminds Canadians of the very real consequences of failing to act in this area: an empty plate. It also helps to bring a sense of immediacy to a threat which is currently distant. One of the many challenges climate policies face is that they seek to address problems that have not yet occurred and are viewed as a lower risk than other, more immediate, issues. By linking climate change to food security, it brings the problem of climate change home for many people. Perhaps framing climate change as a problem to be addressed sector by sector, as opposed to one massive, catastrophic threat, is a potential solution to garner significant public interest and support to create effective climate mitigation policies. In any case, this is what the Protect Your Plate narrative attempts to do.

Another key arc encompassed within the Protect Your Plate narrative is one of innovation. Agriculture is not typically seen as an exciting or innovative industry – in fact, it often gives the impression of just the opposite. However, there is a lot of potential in agriculture to harness new technologies or outside-of-the-box farming methods to transform agriculture as we know it. The three proposals contained in this policy agenda transform agriculture and seek to bring a sense of excitement to an often unglamourous industry. Marrying the immediacy of food security with this sense of transformation results in a narrative that is strong, determined to be heard, and one which presents an opportunity for Canada to shine.

ADAPT

This proposal creates a bookended incentives program to encourage the adoption of adaptive and climate-smart changes on agricultural operations. I propose the introduction of two linked incentives. First, I propose the establishment of a fund available for farmers to make climate-positive changes on their farms. This will be followed by the offer of a reduction in insurance premiums for farmers who successfully make these changes to a pre-determined threshold. This proposal is designed to inspire a high degree of participation amongst producers, and to ease the burden of making the often expensive and difficult changes required to build resilience to climate change in agriculture. As the level of incentives offered in this proposal is high, it has been scoped to key agricultural provinces in Canada. Ontario, Quebec, and the Prairies grow the majority of Canada’s food, and are therefore the beneficiaries of the ADAPT proposal (AAFC 2021f).

Currently, the On-Farm Agricultural Climate Action Fund provides $200 million for precisely the same purpose as ADAPT proposal (AAFC 2022). However, as we will see in later discussions of costing, the ADAPT proposal takes a much bolder approach and seeks to provide an unprecedented level of incentives to producers to encourage participation. Sustainable farming practices are also currently supported by the Canadian Agricultural Partnership, a cost-shared initiative which funds a variety of agricultural programs in participating provinces (AAFC 2021d; Government of Canada 2021a). Agricultural crop and livestock insurance and business risk programs are offered under the Canadian Agricultural Partnership, via the AgriRecovery, AgriStability, and AgriInsurance programs, among others (AAFC 2019a; AAFC 2019b; AAFC 2021c). These insurance programs fall under federal jurisdiction and are delivered on authority granted through the Farm Income Protection Act (Government of Canada 1992).

Design, Governance & Implementation

The proposed design and implementation of this policy is as follows. A fund, titled the Protect Your Plate Fund, will be created. Farmers can access this fund to make changes on their operations that build resilience to climate change. There are several changes of this kind a producer can implement, including practices which capture carbon in soil, improve biodiversity, integrate crops and livestock, diversify crops, among other beneficial activities (Global Impact Investing Network 2022). These changes often go against traditional ‘big’ agriculture practices, which prioritize yield, and are expensive to initially implement. As such, producers have been unwilling to take on the burden of making these changes without government support. The Protect Your Plate Fund will expand the level of incentive offered currently through the On-Farm Climate Action Fund to encourage greater participation in the program. The Protect Your Plate Fund will be administered by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and delivered provincially through pathways established through the Canadian Agricultural Partnership.

Following the administration of the Protect Your Plate Fund, a second incentive will be offered to prompt producers to make significant climate-positive changes on their farms to a certain threshold. A certification program will be created to assess the level of climate change resilience displayed on a farm. Farms that meet the minimum threshold will be granted Plate Protector status and become eligible for a reduction on their crop or livestock insurance premiums. A similar incentive was recently offered by the Government of Alberta in 2021 – the province offered a 20% reduction in crop insurance for producers, which was met with widespread acceptance (Alberta 2021). Offering insurance premium breaks has the twofold benefit of providing financial relief as well as encouraging producers to insure their crops or livestock. This is a critical practice to minimize business risk and another key piece of building resilience to climate change on farms. Further, the creation of a sustainable farming certification system could pave the way for future federal sustainable farming standards or other funding programs which hinge on certification. A proposed timeline for the ADAPT initiative is outlined in Table 1. The bookended design of the ADAPT incentives mimics a set-up and punchline style, so to speak, where continued sustainable action is encouraged in order to collect the maximum level of incentives.

Regarding governance of this proposal, ADAPT is a slight departure from existing agricultural programming. As was previously discussed, the primary mechanism for delivering agricultural funding and services is the Canadian Agricultural Partnership. Under this agreement, federal funding is administered to provinces following the successful reporting of performance metrics. This federal funding is combined with provincial funds to implement programming. As such, governance and cost are shared between the federal and provincial governments. The ADAPT initiative will borrow this structure with one major change: all funding will be federal. This is done for two reasons. First, it grants the federal government greater power to determine the criteria for Plate Protector certification and limits the amount of political pressure on this initiative. Second, a fully federal commitment lends a sense of greater national importance to the ADAPT strategy. This is in alignment with the overarching Protect Your Plate narrative weaving through this policy agenda. This policy agenda tells a story of food insecurity – a potential national crisis – therefore it follows logically that the federal government would lead. As well, this policy agenda sits at the intersection of agriculture and environment. The federal government has been the foremost voice on climate change mitigation in Canada; ADAPT seeks to support climate mitigation and likewise it makes sense to position the federal government as the central authority for this initiative. The federal government has Constitutional authority to introduce policies regarding agriculture, an area of concurrent jurisdiction between the federal and provincial governments (Government of Canada 1867).

Costing

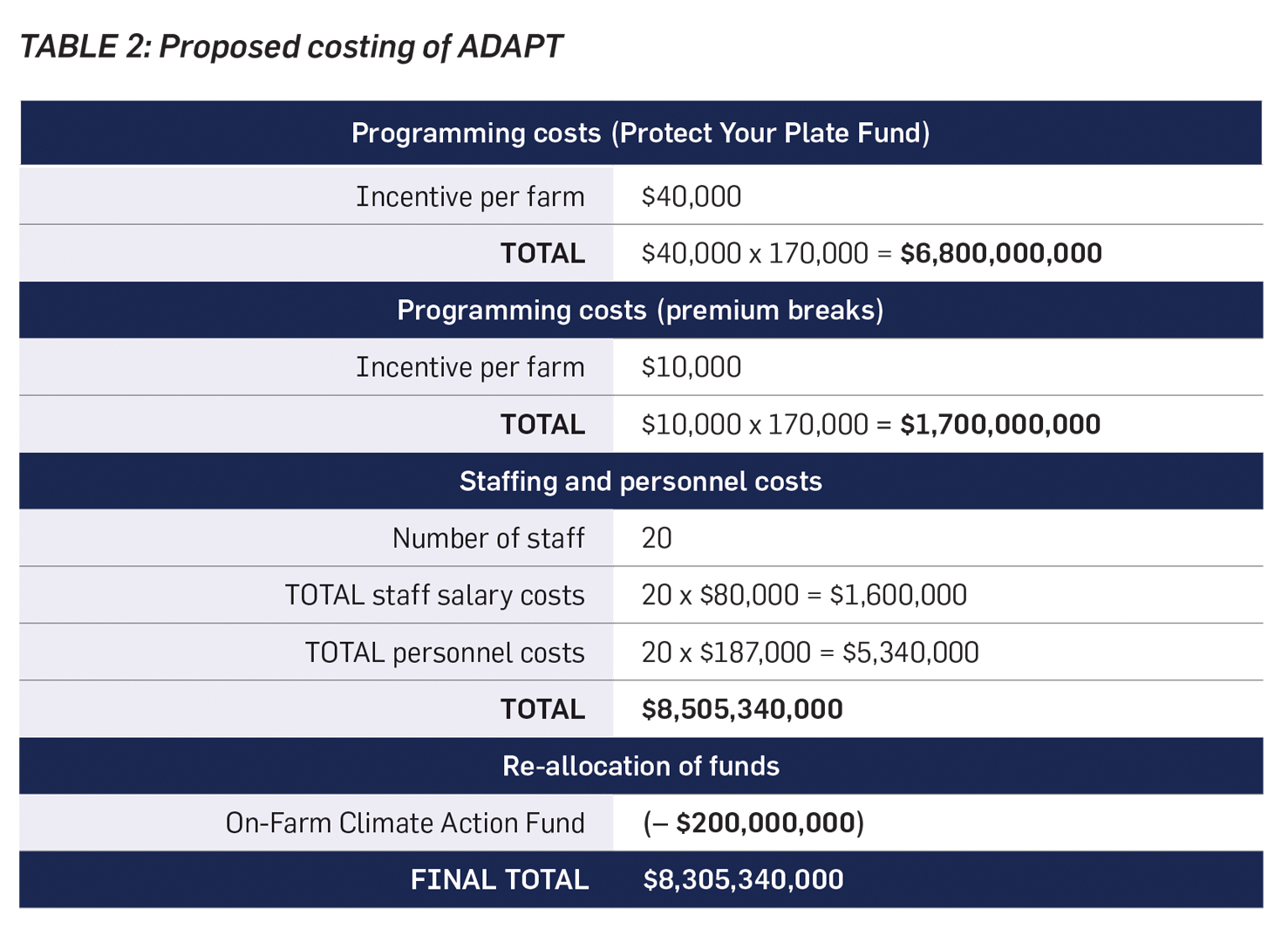

With regards to costing, I estimate this proposal will cost roughly $8.3 billion per cycle to implement, where a cycle refers to the full run through of ADAPT from administration of the Protect Your Plate Fund to discounting insurance premiums for eligible Plate Protectors. This costing takes into account funding needed to support the Protect Your Plate Fund, the discount on insurance premiums, and staff and personnel costs to run the program. A detailed breakdown of anticipated costs is outlined in Table 2. The ADAPT proposal seeks to inspire widespread participation in provinces where this funding will be made available – Ontario, Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. As such, costing estimates were calculated using a simple question: how much funding, ideally, would this program like each producer to receive? To implement on-farm climate adaptive practices, an estimate of $40,000 per farm was decided upon using funding amounts approved for the On-Farm Climate Action Fund (AAFC 2022). This amount, multiplied by the number of farms in Ontario, Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, totals around $6.8 billion. The number of farms is based off the count of farms totalled in these provinces in the 2016 Census of Agriculture, which was rounded up to 170,000 (Statistics Canada 2017).

Costing for the insurance premium discount program was calculated using a similar method. An incentive of $10,000 per farmer was selected as the desired incentive for this program and multiplied by the 170,000 estimated potential farms which could collect it to total $1.7 billion. This costing was estimated based on how much the Government of Canada paid out directly to farmers in 2021 – around $5.9 billion for all of Canada (Statistics Canada 2021). Together, these program costs come to approximately $8.5 billion. $200 million was subtracted from this total, representing the re-allocation of already committed funds for the On-Farm Climate Action Fund, which serves the same purpose as the ADAPT proposal (AAFC 2022). This brings the final programming cost total to approximately $8.3 billion.

With regards to estimating staff and personnel costs, the same calculation was used for each of the three proposals in this policy agenda. As such, what follows is the method used in later costings for the LEARN and INNOVATE initiatives. Using data from the Government of Canada, the average salary of a federal public servant was determined to be $78,740.50 (Treasury Board Secretariat 2021). This was rounded up to $80,000. The average personnel cost per staff was estimated using data from the Public Accounts of Canada, which listed spending on personnel costs in 2021 as around $59.6 billion (Government of Canada 2021a). This was divided by the number of federal public servants in 2021 – 319,601 – to determine an average personnel cost per staff member of $186,554.49 (Treasury Board Secretariat 2021). This was rounded up to $187,000. Twenty staff are recommended to implement the ADAPT proposal – to liaise with provincial and territorial partners, administer the Protect Your Plate Fund, and develop the certification program – leading to an estimate of $5.3 million needed for staff and personnel costs. This brings the total estimate cost of the ADAPT proposal to $8,305,340,000.

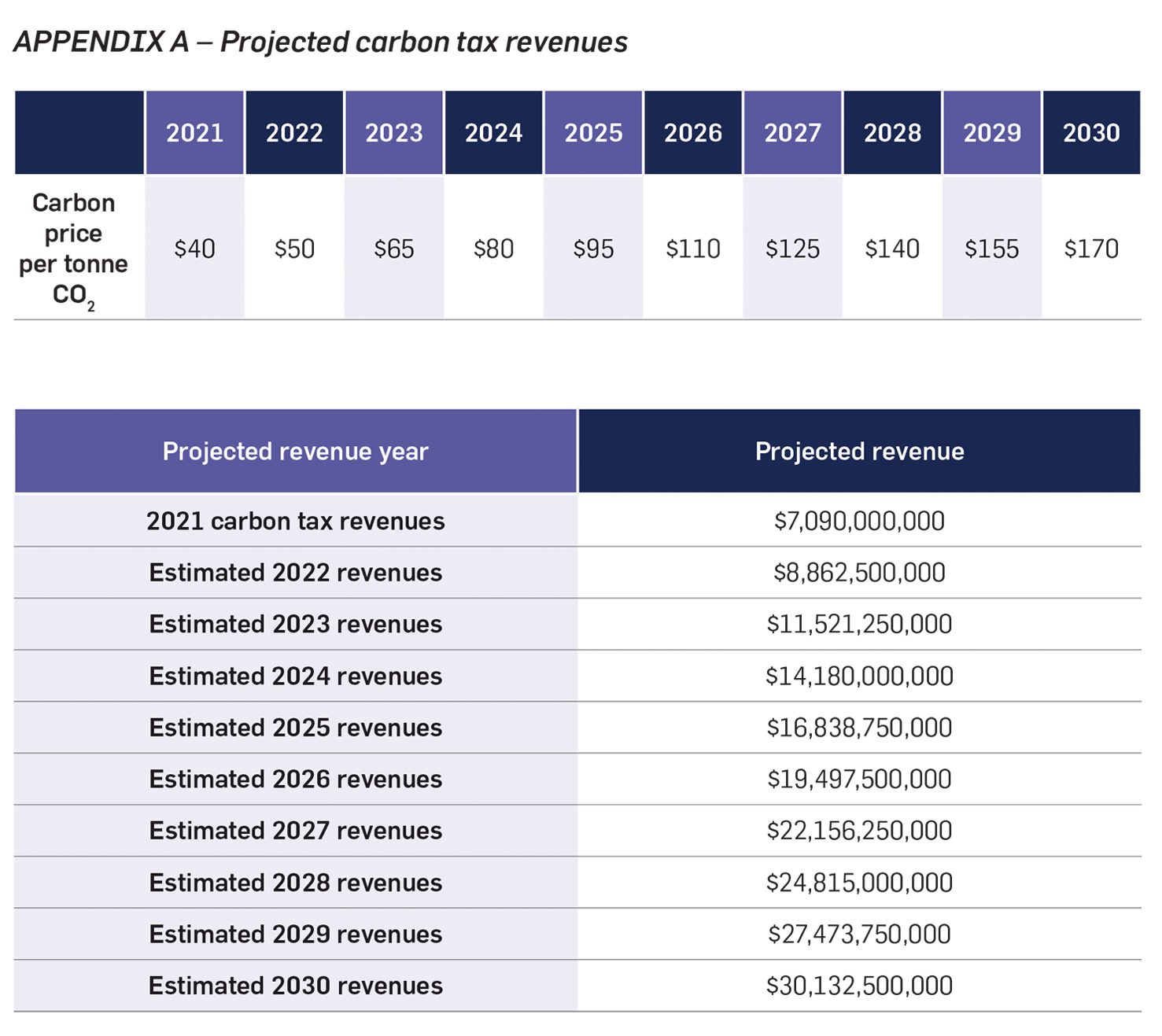

The ADAPT proposal will be paid for by revenue from the carbon tax. In 2021, at a price of $40 per tonne of carbon, the carbon tax generated over $7.09 billion in revenue. The carbon price increased to $50 in 2022, and is set to increase by increments of $15 between 2023 and 2030 until a final price of $170 per tonne of carbon (ECCC 2021). Estimated revenues from the carbon tax in 2023 are over $8.8 billion, which is more than enough to fund the ADAPT initiative, and only set to increase in further years (see Appendix A for projections). Using the carbon tax to fund this initiative creates a nice narrative thread – farmers, after all, are one of the parties most impacted by the imposition of the carbon tax. It may very well soothe some disgruntled producers to know that the tax they heavily pay into will be used to provide them incentives. Further, this proposal does not attempt to change the Government of Canada’s promise to keep the carbon tax revenue neutral. Revenue generated by the tax is being used to fund new initiatives, not to fill the Government’s coffers.

LEARN

This proposal will build awareness of the link between climate change and agriculture through educational programming and advertising. The goal of the LEARN proposal is to support producers in the transition towards more sustainable farming practices, while still recognizing farmers as notable stewards of the land. This proposal offers scholarships for sustainable agriculture courses, certificates, and diplomas at continuing education institutions across the country. In addition, I propose the scholarships be paired with an awareness campaign directed at producers to boost knowledge of this program, government funding opportunities, and information on how to build resilience to climate change in agriculture. This is a strategy that is currently not attempted by federal or provincial governments. Current scholarships for sustainable agriculture programs are unique to each school and reliant on donations for funding.

Design, Governance & Implementation

The design of the LEARN proposal hinges on partnership. Working alongside Canadian colleges and universities, funding for 30,000 scholarships of $500 will be made available. Fees for continuing education agricultural courses range from $200-$900 (see Appendix B for selection of continuing education courses used to establish this average). The $500 provided via the LEARN initiative will therefore meaningfully reduce tuition for any course offering. The intention of these scholarships is to make it easier for producers to receive an education in sustainable farming, on-farm climate resilience methods, and the benefits of mitigating climate change for farmers. Alongside the scholarships, a ‘Protect Your Plate, Canada’ awareness advertising campaign will be launched. The awareness campaign is designed to increase knowledge of the scholarships, as well as to direct producers towards a ‘Protect Your Plate’ homepage, where information on resources and funding for producers will be available. Partnership opportunities will also be sought between government and producer member organizations, of which there are several across the country (Dairy Farmers of Canada, Ontario Federation of Agriculture, Alberta Beef Producers, etc.), to aid in spreading word of the LEARN program through local networks. A proposed timeline of the

LEARN initiative is shown in Table 3.

I propose a shared governance model for the LEARN program. Since education falls under provincial jurisdiction and agriculture under concurrent federal-provincial jurisdiction, significant federal-provincial-territorial cooperation will be required to develop and implement this initiative. In a similar model to existing agricultural programs, LEARN funding will be administered to each province and delivered via provincial pathways. Provinces will be required to provide reports on uptake and success of the program. It is unlikely that significant difficulties will arise in these federal-provincial-territorial negotiations. While provinces may wish for funding to support key industries or research other than agriculture, an argument can be made that producers contribute to the GDP of each province, and quite significantly in the cases of Ontario, Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta. There is also no requirement to cost-share this proposal, which costing estimates reflect, and therefore no burden placed on provincial resources through the implementation of this program. The awareness campaign will remain under federal governance.

Costing

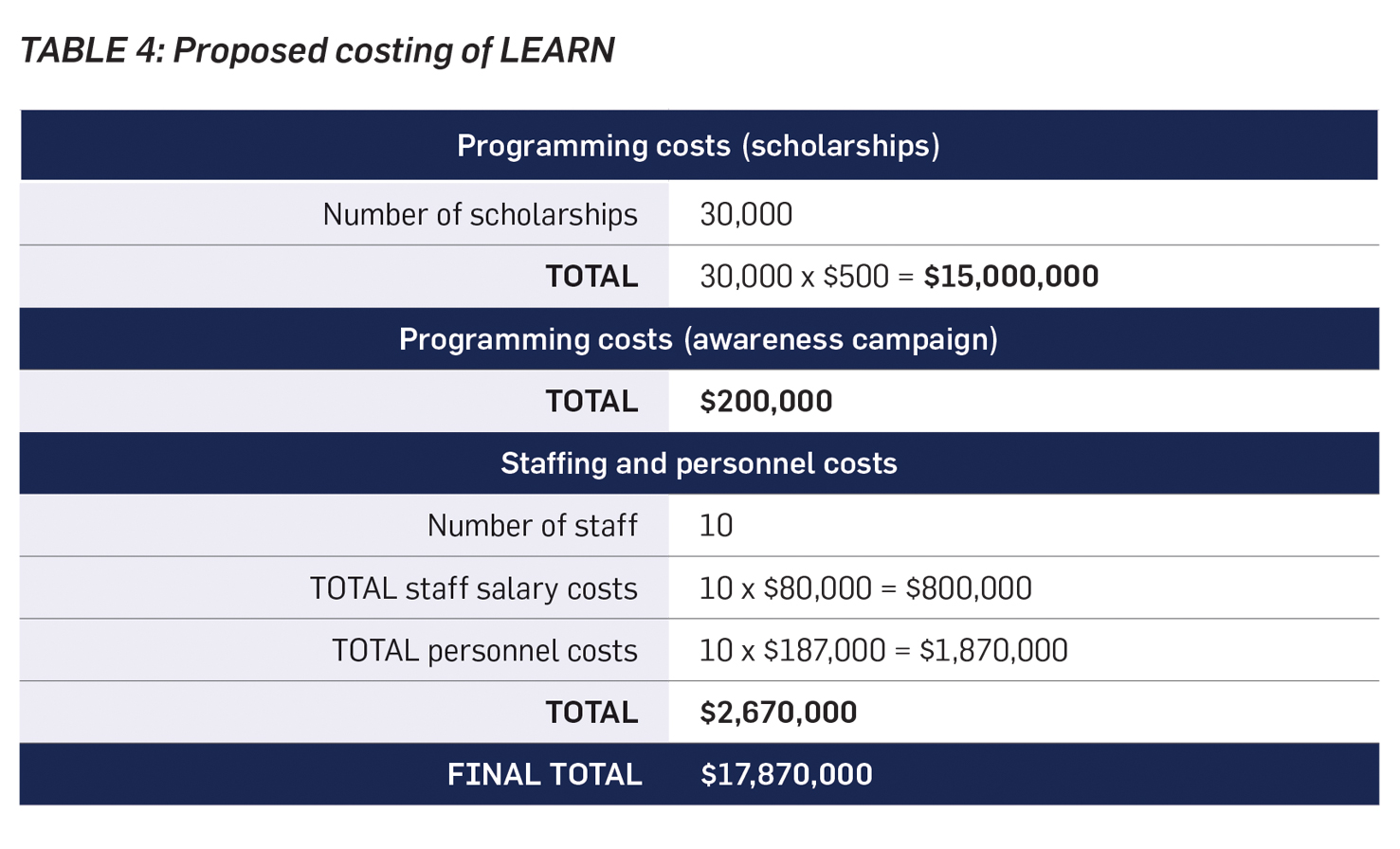

The LEARN proposal will cost an estimated $17 million for each year of operation. Details of this costing are laid out in Table 4. $15 million will be needed to fund the scholarships, $200,000 for the advertising campaign, and roughly $1.8 million for staff and personnel costs for ten staff. The advertising campaign estimate is based on government spending on advertising and awareness campaigns in 2021-22 (Government of Canada 2021b). Similar to the ADAPT initiative, and indeed all three initiatives in this policy agenda, the LEARN proposal will be paid for by revenues from the carbon tax. Currently, a portion of carbon tax revenues ($98 million in 2020-21) are returned as a tax credit to public institutions, including colleges and universities (Government of Canada 2021a). The LEARN funding is a re-allocation of this funding, which is already set aside to support educational institutions. Further, as revenues from the carbon tax are only set to increase with the rise in the price of carbon, using this revenue stream has the benefit of supporting program extension in the future.

INNOVATE

This proposal creates a regulatory sandbox to inspire innovations in agricultural technologies and practices. A regulatory sandbox suspends regulations within a contained space to allow for the testing and piloting of new ideas (UNSGSA 2017). Agriculture is subject to fourteen acts governing production and well over 200 different regulations. These regulations cover all aspects of agriculture, are highly detailed and technical, and represent a significant barrier to innovation in agriculture (AAFC 2021e). I propose a regulatory sandbox, therefore, as an excellent opportunity to advance research, commercialization, and progress in a much-needed area: clean, green agricultural technologies and practices.

The Government of Canada currently offers the AgriInnovate program through the Canadian Agricultural Partnership, which provides funding for applicants to accelerate the commercialization, adoption, and demonstration of products to boost the competitiveness and sustainability of the agricultural sector (AAFC 2021b). The focus of AgriInnovate, then, is quite broad. The proposed INNOVATE initiative will re-configure and expand the AgriInnovate program to be focused exclusively on sustainable development, in addition to lifting regulatory burdens. In addition, the federal Agricultural Clean Technology Program, introduced as part of Budget 2021, provides funding to develop projects that support clean agricultural research or the adoption of clean agricultural technologies (AAFC 2021a). The Agricultural Clean Technology Program does have a specific focus on sustainability and further is still currently accepting applications – therefore the INNOVATE proposal will serve as a supporting, complementary initiative to be offered as part of a suite of innovation-focused agricultural programs alongside the Agriculture Clean Technology Program. Further, interest is so great in the Agricultural Clean Technology Program that applications have been suspended to avoid overrunning staff. Clearly, there is demand for programs of this sort.

There is no precedent for a program like this. In Mississippi, a bill was brought forward to create a regulatory sandbox farm technology innovation pilot program, but it died in committee shortly after referral (Mississippi 2021). Regulatory sandboxes are typically created in relation to financial technology or other, more traditional, technology fields and have not been launched regarding agriculture. The INNOVATE proposal represents the most exciting, cutting-edge proposal within this policy agenda. INNOVATE offers the possibility of Canadian leadership in the agricultural technology sector and seeks to breathe new life into perceptions towards agriculture.

Design, Governance & Implementation

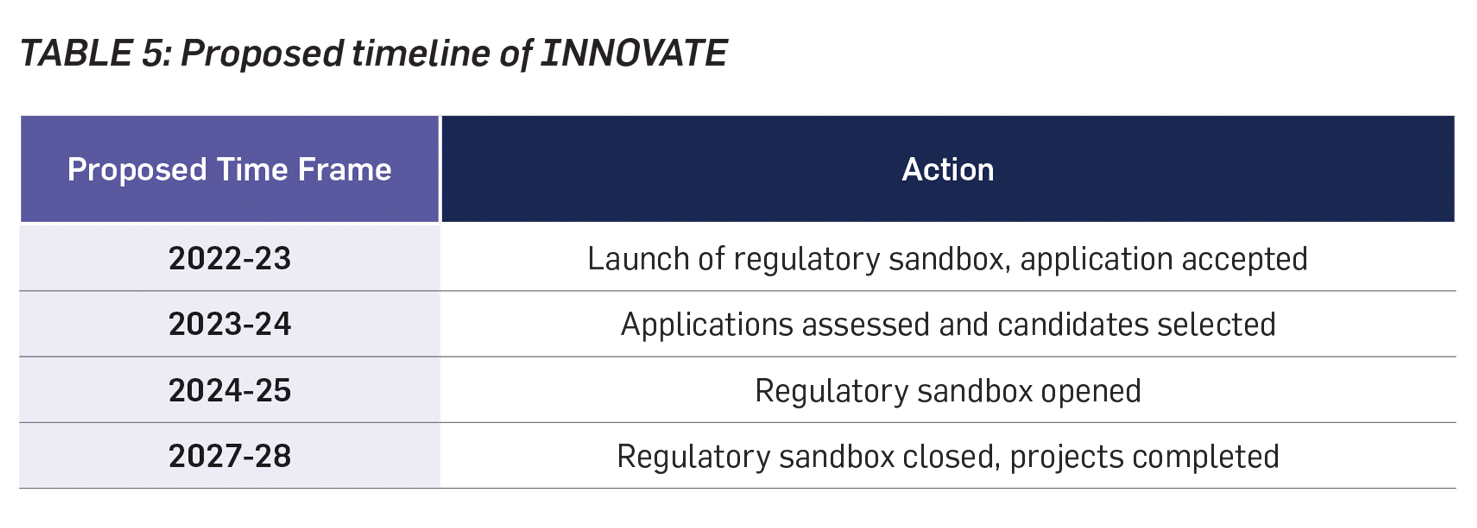

The design of the INNOVATE proposal is as follows. A Canada-wide call for proposals will be launched, supported by an advertising campaign to reach the widest audience possible. Applications will be collected over the course of a year, then assessed and selected for progress over an additional year. Selected candidates will be eligible for up to $10 million dollars to work on their projects and will be subject to a timeline of two years to complete their work. A proposed timeline for the INNOVATE initiative is shown in Table 5.

Special attention will be paid to applications for the sandbox which focus on two distinct areas: the commercialization of zero-emissions farming machinery and the piloting of urban farming practices or technologies. These are two areas of research and innovation that have been identified as promising solutions for how to build resilience to climate change in agriculture. Currently, zero-emissions farm machinery is not commercially available in any market. It is important to advance research in this area as emissions from farm machinery like tractors, grain dryers, and harvesters accounts for a significant portion of agricultural greenhouse gas emissions (Ahmed, et al. 2020, 15). Transitioning these machines away from fossil fuels is a key strategy to mitigate climate change and reduce the likelihood of extreme weather events and disruptions to the agricultural sector. It is estimated that a call for the mass displacement of fossil fuel-based farm machinery will occur worldwide starting in 2050 (16). The INNOVATE proposal could be the key to advancing Canadian leadership in this upcoming market.

Urban farming, as well, has been described as a critical area to explore as a method of building resilience to climate change in agriculture (Dubbeling, van Veenhuizen & Halliday 2019, 32). The shrinking availability of viable farmland across Canada, as well as the need to introduce more sustainable methods of farming, support urban agriculture as an ideal solution to these problems (Stall-Paquet 2021). Urban farming methods, in addition, tend to advance more outside-of-the-box ideas, as they do not have the historical constraints of traditional farming to contend with. This innovative spirit is key for introducing the kinds of transformative ideas in agriculture which will result in meaningful change.

The INNOVATE initiative will be administered and overseen by the federal government. Federal-provincial-territorial negotiations will be required to address provincial regulations regarding agriculture. As the primary regulators of agriculture, the provincial and federal governments have the authority to halt regulations within a controlled environment and create a sandbox. Clear governance is important for effectively operating a regulatory sandbox, and therefore these negotiations should be detailed and formalized prior to the launch of the sandbox (Jenik & Duff 2020).

As well, the INNOVATE proposal will prove relatively easy to sell to policymakers, as it presents a ‘quick win’ option. First, it is clear through the implementation of existing programs such as AgriInnovate and the Agricultural Clean Technology Program that it is possible to make this idea work and that there is sufficient interest from the public in ventures like this. Second, a sandbox is politically palatable. The connection between regulatory sandboxes and innovation lends them an aura of excitement that makes for a good headline and smooth political sale.

Costing

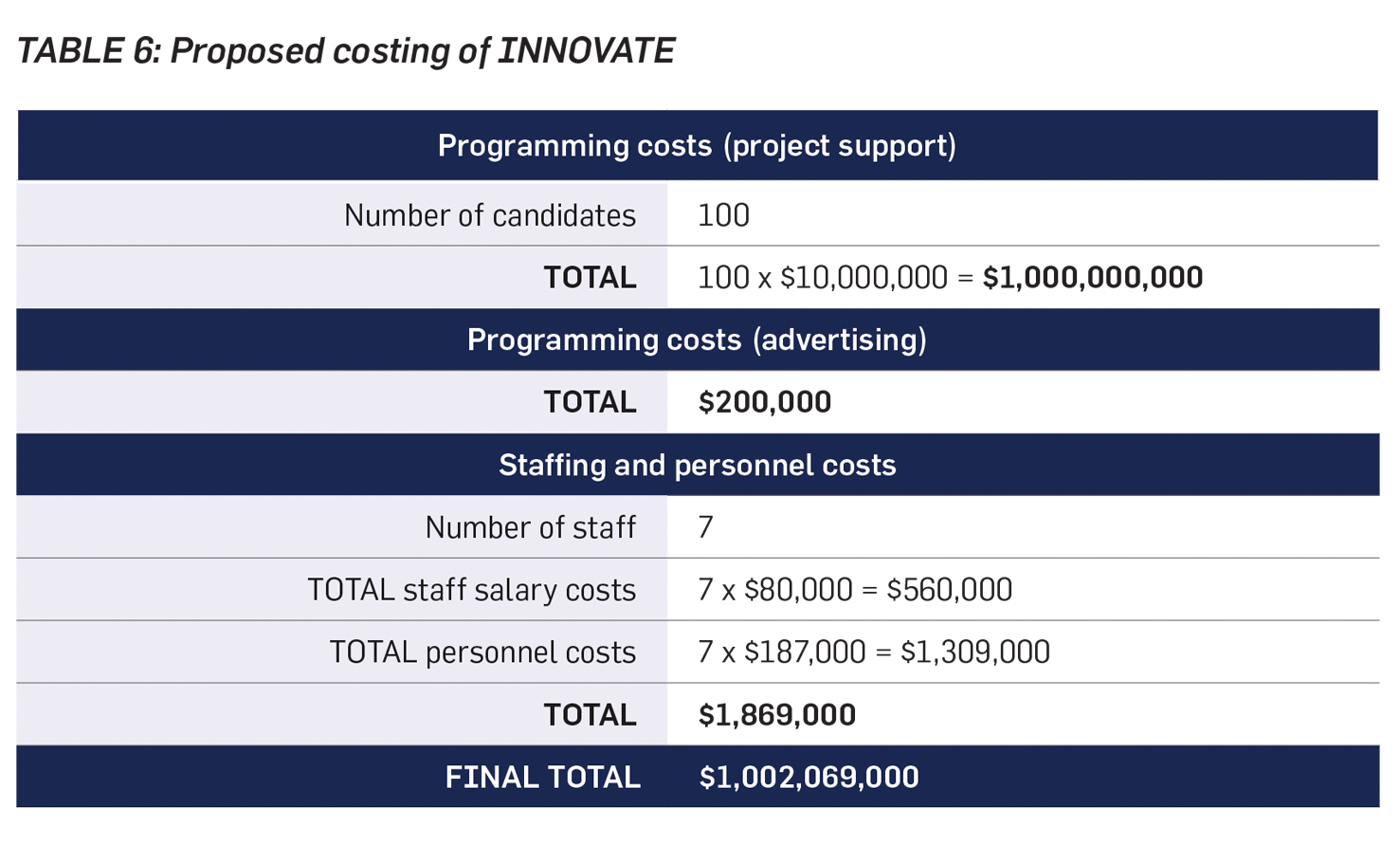

I propose an estimated annual cost of just over $1 billion for the INNOVATE program. These costs cover funding to support eligible projects, advertising costs, and staff and personnel costs. A detailed calculation of estimated costs is shown in Table 6. Similar to the method used to cost the ADAPT initiative, INNOVATE costs are based on a simple question: how much funding should each selected candidate receive for their project? A maximum funding amount of $10 million was chosen, based on the AgriInnovate program, which administers the same for its participants (AAFC 2021b). A goal of one hundred candidates was selected as the desired amount for the first year of the INNOVATE program. As seen through the Agricultural Clean Technology Program, there is high demand for innovation and research focused programs in agriculture. However, the idea of a regulatory sandbox is yet untested in this space. As such, one hundred initial projects will serve as a benchmark for future progress of the initiative. If interest is high and the program yields success, INNOVATE can easily be expanded. Given this estimate of one hundred program recipients, and the maximum funding amount of $10 million, programming costs to support the sandbox’s research projects is estimated at $1 billion. $200,000 is estimated for the INNOVATE advertising campaign, which, just as in the LEARN proposal, was based off federal advertising expenses in 2021 (Government of Canada 2021b). Finally, seven staff are estimated to operate the sandbox. The resulting staff and personnel costs associated with this are around $1.3 million. Once again, the INNOVATE proposal will be funded through carbon tax revenues.

Conclusion

This policy agenda introduced the Protect Your Plate initiative, composed of three distinct policy options: ADAPT, LEARN, and INNOVATE. Each of these proposals seeks to build resilience to climate change in Canada’s agricultural sector to ensure a safe and stable supply of food. ADAPT recommends the distribution of an unprecedented level of incentives for farmers to make meaningful changes on their agricultural operations to safeguard against the disruption of climate change. The two-part incentive program offered via ADAPT will provide funding to ease the burden of making climate-smart changes in key agricultural areas and follow this with a reduction in insurance premiums for farms that make changes up to a pre-determined threshold. The LEARN proposal will build resilience to climate change by changing attitudes and building awareness of the link between agriculture and climate change in Canada’s producers. A targeted awareness campaign and the offer of scholarships for continuing education programs in sustainable agriculture make up the LEARN proposal. Lastly, INNOVATE will create a regulatory sandbox to jump-start agricultural innovations to reduce greenhouse gases, transform how farming is done, and better prepare Canada’s agriculture sector for the disruption of climate change.

The Protect Your Plate policy agenda is an effort to improve the social and economic well-being of Canadians by protecting a necessity of life: food. The ability to access food with relative ease in Canada is central to the country’s foundation as a safe, dependable, and strong place. The threat climate change presents to agriculture is inevitable. Therefore, we must prepare now. We must protect our plates, and this policy agenda presents three options to do so.

Erin Mierdel holds a Master of Public Policy from the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy at the University of Toronto and a Bachelor of Arts & Science from McMaster University. Erin works as a Junior Policy Analyst at Public Safety Canada and, prior to that, completed a co-op term with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture & Rural Affairs.

Bibliography

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). 2019a. “AgriInsurance Program.” Canada.ca. Government of Canada. October 29, 2019. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/agricultural-programs-and-services/agriinsurance-program.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2019b. “AgriRecovery.” Canada.ca. Government of Canada. October 9, 2019. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/agricultural-programs-and-services/agrirecovery.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2020a. “Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture.” Canada.ca. Government of Canada. January 31, 2020. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/agriculture-and-environment/climate-change-and-air-quality/climate-scenarios-agriculture.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2020b. “Outline of Opportunities in China.” Canada.ca. Government of Canada. April 1. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/international-trade/market-intelligence/reports/outline-opportunities-china.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2021a. “Agricultural Clean Technology Program: Adoption Stream: Step 1. What This Program Offers.” Canada.ca. Government of Canada. September 3, 2021. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/agricultural-programs-and-services/agricultural-clean-technology-program-adoption-stream.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2021b. “AgriInnovate Program: Step 1. What This Program Offers.” Canada.ca. Government of Canada. March 30. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/agricultural-programs-and-services/agriinnovate-program.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2021c. “AgriStability: Step 1. What This Program Offers.” Canada.ca. Government of Canada. June 15, 2021. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/agricultural-programs-and-services/agristability.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2021. “Canadian Agricultural Partnership.”

Canada.ca. Government of Canada. June 24. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/about-our-department/key-departmental-initiatives/canadian-agricultural-partnership.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2021d. “List of Acts and Regulations.”

Canada.ca. Government of Canada. April 19, 2021. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/about-our-department/transparency-and-corporate-reporting/acts-and-regulations/list-acts-and-regulations.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2021e. “Overview of Canada’s Agriculture and Agri-Food Sector.” Canada.ca. Government of Canada. November 5, 2021.

https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/canadas-agriculture-sectors/overview-canadas-agriculture-and-agri-food-sector.

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2022. “Agricultural Climate Solutions – On-Farm Climate Action Fund.” Canada.ca. Government of Canada. February 23, 2022.

https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/agricultural-programs-and-services/agricultural-climate-solutions-farm-climate-action-fund-0.

Agriculture in the Classroom Canada. 2022. “Provincial Members.” AITC Canada. 2022. https://aitc-canada.ca/en-ca/who-we-are/provincial-members.

Agriculture Financial Services Corporation. 2019. “Mandate & Roles Document.” AFSC. 2019. https://afsc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Mandate-Roles-Document.pdf.

Ahmed, Justin, Elaine Almeida, Daniel Aminetzah, Nicolas Denis, Kimberly Henderson, Joshua Katz, Hannah Kitchel, and Peter Mannion. 2020. Agriculture and Climate Change. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/agriculture/our%20insights/reducing%20agriculture%20emissions%20through%20improved%20farming%20practices/agriculture-and-climate-change.pdf.

Alberta Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. 2021. “20% Off Crop Insurance for Alberta Farmers.” Alberta.ca. Government of Alberta. January 25. https://www.alberta.ca/article-20-per-cent-off-crop-insurance-for-alberta-farmers.aspx.

The Associated Press (AP). 2022. “Catastrophic Wildfires Could Increase 50% by 2100, UN Report Says.” CBC. February 24, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/news/science/extreme-wildfires-unep-nature-1.6361093.

Canada Production Insurance Regulations, SOR 2005-62. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/SOR-2005-62/index.html

Constitution Acts, 1867 to 1982, S.C. 1982. http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/

Climate Atlas of Canada. 2017. “Agriculture and Climate Change.” Climate Atlas of Canada. 2017. https://climateatlas.ca/agriculture-and-climate-change.

DeLind, Laura B. 1990. “Agriculture, Education and Industry: A Progressive or Problematic Partnership for Michigan?” Michigan Sociological Review Fall (4): 20–32.

Dubbeling, Marielle, Rene van Veenhuizen, and Jess Halliday. 2019. “Urban Agriculture as a Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction Strategy.” Field Action Science Reports 20: 32–39.

Eagle, Alison J., James Rude, and Peter C. Boxall. 2016. “Agricultural Support Policy in Canada: What Are the Environmental Consequences?” Environmental Reviews 24 (1): 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2015-0050.

Environment and Climate Change. 2021. “Update to the Pan-Canadian Approach to Carbon Pollution Pricing 2023-2030.” Canada.ca. Government of Canada. August 5. https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/climate-change/pricing-pollution-how-it-will-work/carbon-pollution-pricing-federal-benchmark-information/federal-benchmark-2023-2030.html.

Farm Income Protection Act, S.C. 1992, c.22. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/F-3.3/

Global Impact Investing Network. 2022. “Improving Climate Resilience Through Agriculture.” GIIN. Accessed April 6. https://navigatingimpact.thegiin.org/strategy/sa/improving-climate-resilience-through-agriculture/.

Government of Canada. 2021a. Public Accounts of Canada 2020-2021.

Government of Canada. 2021b. 2020 to 2021 Annual Report on Government of Canada Advertising Activities. https://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/pub-adv/rapports-reports/documents/rapport-annuel-annual-report-2020-2021-eng.pdf.

Gomez, Michelle. 2021. “Flood Damage Could Cost Farmers Hundreds of Millions of Dollars, B.C. Agriculture Council Says.” CBC. November 26, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/bc-floods-sumas-praire-farms-damage-cost-1.6262667.

Jenik, Ivo, and Schan Duff. 2021. “Regulatory Sandboxes: A Practical Guide for Policy Makers.” CGAP. https://www.cgap.org/research/reading-deck/regulatory-sandboxes-practical-guide-policy-makers.

Lakeland College. 2022. “Ag Crops Continuing Education Courses.” Lakeland College. https://www.lakelandcollege.ca/programs-and-courses/ag-crops-continuing-education#Nutrient-Management.

Mississippi State Legislature. 2021. “Mississippi HB1455: 2021: Regular Session.” LegiScan. https://legiscan.com/MS/bill/HB1455/2021.

Lipski, Candice. 2021. “Sask. Government Announces $119 Million to Aid Drought-Affected Livestock Producers.” CBC. August 10, 2021. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/sask-government-funding-drought-cattle-producers-1.6136856.

Logan, Cloe. 2021. “Agriculture Education in Schools Gets $1.6m Boost from the Feds.” The Star. March 5, 2021. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2021/03/05/agriculture-education-in-schools-gets-16m-boost-from-the-feds.html.

Manitoba Agricultural Services Corporation. 2022. “MASC Insurance.” MASC. 2022. https://www.masc.mb.ca/masc.nsf/insurance.html.

Mbow, Cheikh, Cynthia Rosenzweig, et al. 2019. “Special Report on Climate Change and Land, Chapter 5: Food Security.” IPCC. https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/chapter/chapter-5/.

Michigan Farm Bureau. 2012. “Educational Reforms.” Michigan Farm Bureau. 2012. https://www.michfb.com/mi/policy_and_politics/policies/education/educational_reforms/

Ryerson. 2022. “Dimensions of Urban Agriculture.” The Chang School of Continuing Education. https://continuing.ryerson.ca/search/publicCourseSearchDetails.do?method=load&courseId=25461.

Stall-Paquet, Caitlin. 2021. “Fresh from the City: The Rise of Urban Farming.” Canadian Geographic. July 9, 2021.

https://www.canadiangeographic.ca/article/fresh-city-rise-urban-farming.

Statistics Canada. 2017. “Total Number of Farms and Farm Operators, Census of Agriculture, 2011 and 2016.” Canada.ca. Government of Canada. May 10.

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3210044001.

Statistics Canada. 2021. “Direct Payments to Agriculture Producers.” Statistics Canada. Government of Canada. November 24, 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3210010601.

Treasury Board Secretariat. 2021. “Infographic for Government of Canada.” Canada.ca. https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/ems-sgd/edb-bdd/index-eng.html#infographic/gov/gov/people/.

United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2016. “Climate Impacts on Agriculture and Food Supply.” City of Chicago. 2016. https://climatechange.chicago.gov/climate-impacts/climate-impacts-agriculture-and-food-supply.

University of Guelph. 2022. “Sustainable Urban Agriculture Certificate.” Open Learning and Educational Support. https://courses.opened.uoguelph.ca/public/category/courseCategoryCertificateProfile.do?method=load&certificateId=615989.

UNSGSA. 2017. “Briefing on Regulatory Sandboxes.” UNSGSA.

https://www.unsgsa.org/sites/default/files/resources-files/2020-09/Fintech_Briefing_Paper_Regulatory_Sandboxes.pdf.