Policy Papers

ON360 Transition Briefings 2022 – Homeward Bound: A Reshoring Strategy for Ontario

The supply chain disruptions precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic have led to renewed calls for industrial reshoring across advanced economies, and the Ontario government is no exception. What policies could the Ontario government deploy to strengthen capacities? And should the government's goal be to reshore, or pursue more resilient supply chains?

Issue

The supply chain disruptions precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic have led to renewed calls for industrial reshoring across advanced economies. Governments around the world have increasingly articulated the need to rebuild certain strategic productive capacities such as medical equipment within their borders and some have even set out policy strategies to hasten this trend.

The Ontario government is no exception. Its spokespeople have at different points over the past two years conveyed the importance of domestic manufacturing in general and the need for industrial reshoring in particular. Early in the pandemic, for instance, Premier Doug Ford said the following:

“[We can no longer be] beholden to countries around the world for the safety and well-being of the people of Canada. We have the technology, the ingenuity, the engineering might, the manufacturing might. There is nothing that we cannot build right here in Ontario.”[1]

While the government has since announced a new provincial fund, in partnership with the Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters, to support an “Ontario Made” campaign, it is fair to say that it has yet to put forward a comprehensive strategy to bring expression to the premier’s reshoring or supply chain ambitions.[2]

The basic idea of reshoring is simple enough. It refers to the process of returning domestic manufacturing from foreign markets to the home country where the business’ products are sold. In practice, though, it is far more complex. Policymakers must account for considerations such as the costs and benefits of attempting to reshore certain productive capacities, how to determine which capacities to prioritize in the first place, and whether the ultimate goal ought to be reshoring itself or more resilient supply chains along a regionalized basis or among allied countries.

The context for such emerging policy questions is that globalization of manufacturing production took off over the past 30 years. Consider, for instance, that global trade jumped from 39 percent of global GDP in 1990 to 58 percent in 2019.[3] These trends have been driven by various factors, including sectoral and firm-level responsiveness to marginal production costs.

Advanced economies like Canada experienced significant declines in their manufacturing footprint as production shifted to lower-cost jurisdictions such as China and Vietnam.[4] These employment losses have been offset by an overall increase in global production as well as lower business and consumer prices. This trade-off is the subject of political debate (particularly for some regions, communities, and workers) but on balance economists generally agree that the net effects have been positive in overall terms.[5]

The pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions, however, have renewed the debate about the efficacy and risks of these global supply chains. Bottlenecks and shortages have caused even the most vociferous free traders to question whether there is a role for public policy to support certain strategic domestic production capacities or to improve supply chain resiliency.

This would not represent a full reversal of globalization. Markets would still, by and large, dictate the distribution of production for most manufactured goods. But there may be so-called “strategic” or “critical” manufactured goods – including, for instance, vaccine production – where national or sub-national governments may be prepared to use policy levers to ensure that they maintain certain productive capacities within their borders or among regionalized partnerships.

The key questions in this context are: (1) What policy instruments could the Ontario government deploy to strengthen the province’s productive capacities or improve its access to strategic or critical supplies? (2) What productive capacities or supplies are indeed strategic and critical? (3) Should the government’s goal be to reshore these productive capacities or to pursue more resilient yet still globalized supply chains?

Overview: Supply Chain Efficiency Versus Supply Chain Resiliency

Supply chain disruptions can be caused by many factors, such as natural disasters, geopolitical disputes, transportation failures, cyber-attacks, power outages, labour shortages and pandemics. Disruptions caused by COVID led to shortages of certain manufacturing inputs and finished goods – from N95 masks to semiconductors – which in turn have contributed to renewed calls to re-evaluate global supply chains in the name of reducing vulnerabilities.

The basic premise behind Premier Ford’s comment cited earlier is that jurisdictions like Ontario have made themselves vulnerable by becoming overly reliant on other manufacturing countries – especially ones viewed as geopolitical competitors, such as China – for certain “strategic” or “critical” manufactured goods, including medical equipment, basic pharmaceuticals and even automobiles and lumber for home building.[6],[7]

The magnitude and costs of resulting critical supply shortages have been significant. Early in the pandemic, for instance, front-line healthcare and long-term care workers had to ration masks while taking care of patients, rather than change masks when moving between patients, as is typical protocol. Shortages in personal protective equipment in Ontario more generally have been cited as contributing to 20 percent of positive COVID cases among hospital workers, compared to 14 percent of cases globally.[8]

Prior to the pandemic, such non-financial costs from resiliency risks were underestimated in the context of the overall benefits of global supply chains. The long-term trend towards global supply chains was driven primarily by the goal of efficiency and cost reduction. Sourcing inputs and finished products from around the world could bring production costs down and lower prices for businesses and consumers. There is certainly evidence that this globalization of production, which was supported by parallel declines in transportation and communications costs, had significant effects on prices for certain consumer products.[9] The key was to shift to a globalized model of suppliers and production in the search for low-cost inputs and labour so as to reduce overall costs and ultimately boost profits.

It is hard to overstate the magnitude of these global supply chains as a crucial underpinning of global economic activity. One estimate is that approximately 70 percent of international trade occurs for the purpose of production in global supply chains.[10] This globalized system represents an intricate web of inter- and intra-firm transactions that often involve a significant amount of interregional production sharing. Global supply chains amount to a modern expression of Ricardian comparative advantage.

Yet the pandemic experience has caused policymakers to question whether the drive for efficiency has come at the expense of supply chain resiliency. Supply chain resiliency is defined as the capacity for a supply chain to resist and respond to disruptions and minimize the time needed to recover operational capacity.[11] A September 2021 paper for Chatham House, a London-based think tank, describes a resilient supply chain as one that is “visible, agile, and sustainable.”[12]

There are various arguments made in favour of a policy agenda focused on reshoring. These include a combination of potential employment gains, innovation and productivity gains, and national security considerations.[13] But in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the most common argument is about resiliency.

The basic idea is that an overemphasis on low costs in supply chain decisions has made businesses and even countries susceptible to disruptions including production interruptions. Accounting for resiliency can therefore change the cost-benefit

analysis such that low costs may be superseded by a preference for accessibility and reliability. A fuller accounting of these non-financial considerations can be used to justify government intervention to boost domestic production or support more resilient regionalized supply chains.

This perspective is hardly limited to Premier Ford and other political leaders. Polling published by KPMG Canada indicates that Canadian business leaders have similar concerns about supply chain risks. Its 2020 survey of Canadian CEOs found that

supply chain issues were viewed as the third most significant risk to their future business growth.[14]

This has led some to call for a shift from “just-in-time” systems of production to “just-in-case” (including extra inventory and lead times) and even “just-at-home” (including the domestic production of critical products). The distinction across these different supply chain scenarios would allow for differing treatment for certain manufactured goods. Most consumer products are neither strategic nor critical and should remain part of a globalized system free from government intervention. There may, however, be certain critical manufactured goods such as medical equipment or basic pharmaceuticals in which there is a strong case for government stockpiling or even government-sponsored domestic production or regionalized supply chains.

This point is worth emphasizing: the case for reshoring is most persuasive when narrow and well-defined. It should reflect an evidence-based and strategic view of a jurisdiction’s broad interests rather than a rationalization for something approximating autarky.

The Need for Reform

Yet even if governments believe it is in their jurisdictions’ interests to pursue some level of reshoring, it is not a straightforward exercise. The factors that contributed to offshoring in the first place can be complex. It follows that the right mix of policies to pursue reshoring must account for various factors of production including labour, energy, infrastructure, land, financing, transportation, and regulatory policy. There is no silver bullet in a reshoring strategy.

There is also the basic determination of what production capacities ought to be deemed “strategic” or “critical.”[15] This can be the subject of lobbying and politicization if it is not rooted in a principles-based framework. The standard should be high and involve some combination of national security and national (or sub-national) interests. The worst outcome is one in which these types of policy decisions appear arbitrary and politically motivated.

Policymakers will also have to decide between focusing on supply chain resiliency, reshoring, or a balance of the two to ensure supply and protect against price fluctuations caused by production delays from sourcing jurisdictions. That is to say the overarching goal of greater reliability of supply for strategic or critical goods can be achieved through policy interventions to rebuild domestic productive capacities or bilateral or multilateral partnerships along regionalized lines or among allied countries. The former was the subject of significant attention in the immediacy of the pandemic. But in its aftermath, the latter seems to be receiving greater focus from policymakers.

In defining the dichotomy between industrial reshoring and supply chain resiliency, a trio of Harvard and Princeton professors identified types of shocks (including localized or country wide shocks) and the role government could play in key sectors of the economy using subsidies or taxation instruments.[16]

Localized disruptions typically stem from shocks such as localized extreme weather, labour strikes or prototypical failures that impact downstream firms. Country-wide shocks such as earthquakes, disease outbreaks, political conflicts or transportation system shutdowns can impact all components of a supply chain in many different industries within a single jurisdiction.

To mitigate against disruptions, governments may, in broad terms, rely on two policy instruments to influence how firms decide: subsidies for domestic production or taxes on offshore production.

Encouragement of domestic production can come in the form of capital or operating subsidies. The magnitude of the subsidy and its form may depend on the relative cost of production in a particular jurisdiction. Think for instance of a vaccine production facility. If a government decides that it wants to establish domestic productive capacity, but the marginal production cost for a company is too high for such an investment to occur on a market basis, then the government can lower the production costs by subsidizing the construction of the facility or its ongoing operations. Depending on the circumstances,

it may involve a combination of the two.

Discouragement of international production can come in the form of tariffs, other taxes or procurement restrictions. The idea here is essentially to force a company to produce domestically in order to access the domestic market. There are two problems with this approach: generally, there is the risk of trade challenges under free trade agreements or under World Trade Organization rules; and specifically, the Ontario market may not be big enough for most firms to justify the cost of developing a production capacity solely for the domestic market even with government encouragement.

In more tangible terms, the set of factors that will influence firm behaviour is long, including, for instance, human capital. Discussions with policymakers and businesses highlight a significant emphasis on labour talent and costs. Jurisdictions wanting

to reverse the trend of de-industrialization will have to address the loss of human capital that has occurred in the manufacturing sector in recent decades. As a recent Ontario 360 paper explained:

“Now, with increased retirements in the manufacturing sector due to population aging, eight out of ten companies in the sector are reporting skills shortages, just to keep overall employment at the current level. ”[17]

As policymakers make these judgements, they must also consider the right method of reshoring. If the overall goal is to enable supply chains to adapt quickly to disruptions or spikes in demand, it does not necessarily follow that domestic production is required. There is considerable scope for regionalized supply chains or among allied countries, providing more resilience without going so far as to, in this instance, drive forward with a pure “made-in-Ontario” approach.

One method for evaluating such options is “supply chain mapping.” In basic terms, it involves gathering information about a firm’s or jurisdiction’s suppliers, their own suppliers, and the points in their supply chain in order to create a global map of their supply network. Although such an exercise can be time-consuming and even costly, it can help to identity potential resiliency risks and enable policymakers to address them in the most effective way.

According to the literature on supply chain mapping, a comprehensive supply chain map should account for the following:

“…the geographical location of suppliers; supplier’s suppliers, all the way down to raw materials; manufacturing plants; warehouses and distribution centers; transportation routes; and major markets. They include information on activities performed at each site, alternative sites that can do the same, lead times, shipment frequencies, product mix and volumes, supplier delivery performance, and more. Many organizations also choose to incorporate disruption-related metrics in their supplier evaluations; some even require suppliers to participate in annual mapping efforts.”[18]

The European Union and the United States are also grappling with these questions, including supply chain mapping. Recent reports by the European Round Table for Industry and by the White House, however, reflect different views on how a reshoring strategy should be pursued.

The European Round Table for Industry (ERT), a forum for some of Europe’s largest companies such as Volvo, Airbus, Michelin, Rolls-Royce and others with large supplier bases, has called on the European Union to develop “a clear definition of critical goods [including] those for which supply disruptions could potentially undermine the ability of policymakers to [achieve] core public policy objectives”[19] as part of building up the EU’s so-called “open strategic autonomy.”

Open strategic autonomy is based on two policy goals. The first is achieving mutually beneficial economic growth through an openness to trade, investment, and movement of people. The second is managing economic relationships where strategic vulnerabilities could develop to mitigate material impacts on European citizens.[20] The EU’s geopolitical context is referenced frequently in the report, with recommendations to balance EU-US and EU-China relations while pursuing its own interests.

The EU’s policy of open strategic autonomy has started to manifest itself in recent agreements, including with the U.S. and Canada. Regarding the U.S., the two have established the EU-US Trade and Technology Council as a platform for cooperation on trade policy and related matters.[21] Similarly, in June 2021, Canada and the EU announced a new strategic partnership called the Canada-EU Strategic Partnership on Raw Materials concerning critical mineral supply chains.[22]

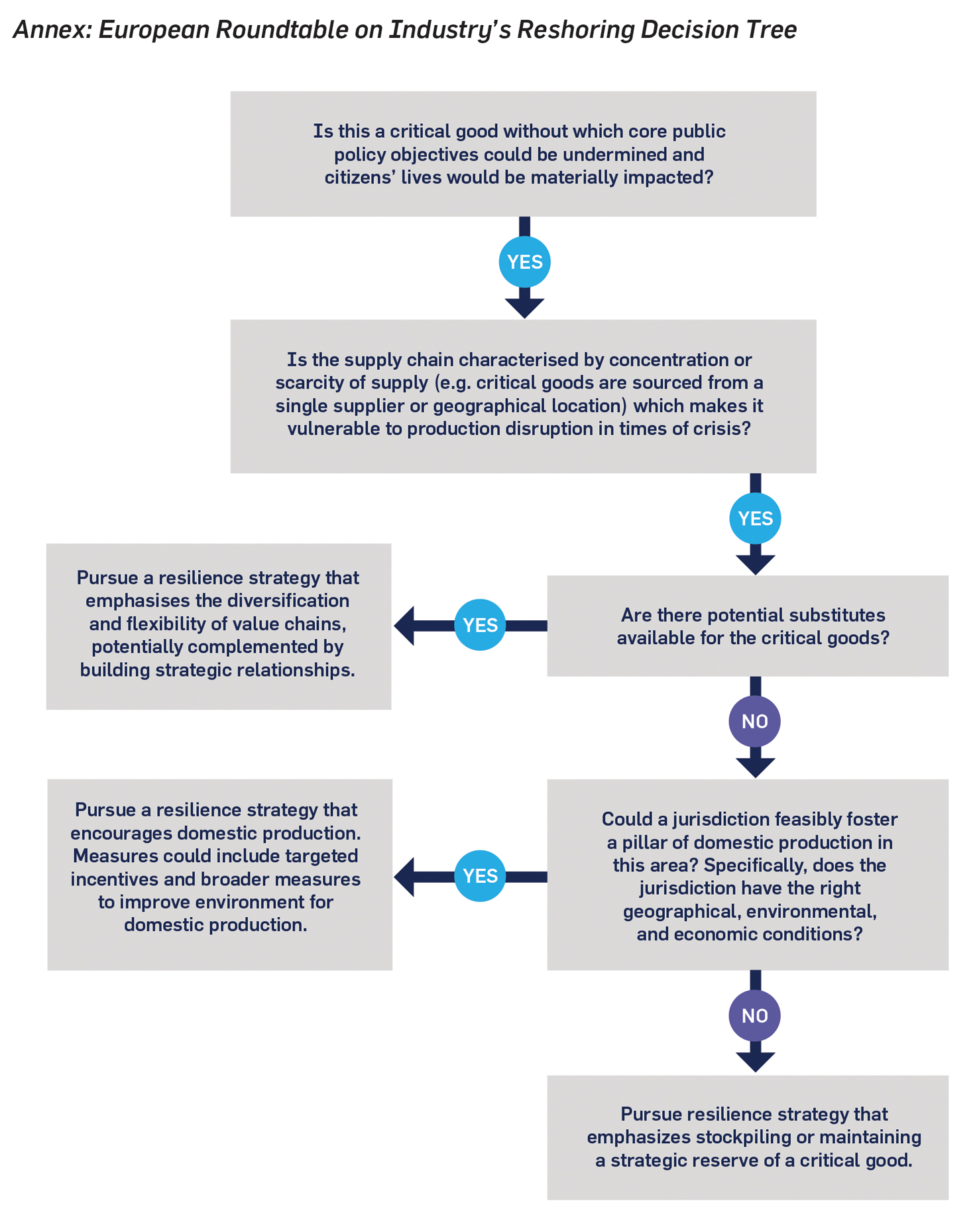

The ERT has produced a reshoring decision tree to help guide policymakers in evaluating (1) if a good is indeed strategic and critical and (2) options with respect to reshoring or supply chain resiliency. (The decision tree is included as an annex to this policy brief.) Instead of a general reshoring policy, the decision tree’s approach helps to crystalize key considerations for policymakers, before deciding on possible reshoring options.

The American approach, outlined in a recent White House’s report[23] on supply chain challenges, has some similarities to the ERT’s thinking as well as some key differences. The biggest contrast is with regards to trade relations with the rest of the world. While the ERT’s report emphasizes the importance of “open strategic autonomy” (which places considerations about strategic or critical goods in an overall pro-globalization context), the U.S. report hints at self-reliance through onshoring and “friend-shoring” critical supply chains.

Friend-shoring has been described by U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen as the notion that “countries that espouse a common set of values on international trade … should trade and get the benefits of trade.” It seems to be gaining momentum as the default approach to the reshoring question for many countries.[24] The Canadian government, for instance, has expressed support for working with the Biden Administration on these issues. As Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland said recently:

“We need to deepen ties between the countries that share values … We’re still going to have a relationship with countries outside this closest circle, but it’s going to be a different sort of relationship. It’s going to be a relationship that has less trust at its heart, that is more careful, where we’re careful not to have as much of a dependency … I think it may require some new institutions, some new relationships, but I think this is where we really need to go.”[25]

It is too early to know if new institutions may emerge, but the Biden Administration has already executed an executive order to “undertake a comprehensive review of critical U.S. supply chains to identify risks, address vulnerabilities and develop a strategy of resilience.”[26]

The resulting White House report[27] identifies four critical sectors of the economy:

- Semiconductor manufacturing and advanced packaging

- Large capacity batteries

- Critical minerals and materials

- Pharmaceuticals and active pharmaceutical ingredients

It sets out the causes of American supply chain challenges as: offshoring, misaligned incentives and short-termism, competing nations’ industrial policy, geographic concentration of sourcing and limited international coordination. The report recommends several high-level policies to mitigate or offset factors that might impede reshoring or supply chain resiliency ranging from targeted interventions at the individual level to industry-wide policies.

They include measures such as:

- Domestic financing and funding programs for identified key industries

- Consumer side rebates and incentives

- Supply chain monitoring and stockpile strengthening

- Use of government procurement to bulk-purchase critical goods

Policymakers in Ontario and Canada may find these reports instructive. The Canadian context is particular, of course, given our geographic proximity to and economic dependence on the United States.

How to Move Forward

Given the considerations outlined above, here are four suggestions for Ontario policymakers to guide their thinking and planning on this growing issue at this early stage.

1. Map Ontario’s Supply Chains

Both the EU and US are carrying out exercises to map their supply chains to better understand their vulnerabilities. A mapping exercise would provide the public and private sectors with a clearer picture of where the province is best positioned to capitalize on its strategic advantages, possibly to reshore production. As the White House puts it:

“The data and mapping from the survey allows the office to run stress tests for various shocks, including a cyber attack at a critical node, and run scenario planning exercises to facilitate greater preparedness across the private sector and government agencies to respond to potential shocks to a critical supply chain.”[28]

This may be a project that can be carried out as a partnership with the federal government and/or with the other provinces via the Council of the Federation. The key point though is that a mapping exercise can provide a common and

well-established understanding of Ontario’s supply chains and their resiliency risks in order to guide evidence-based policymaking.

2. Establish Supply Chain Monitoring Capabilities

The provincial government should create monitoring capabilities through an all-government approach, in consultation with private sector partners in strategic industries. Supply chain monitoring enables the government and private sector to identify risk areas, observe early indications of potential disruptions, and provide targeted responses to counter anticipated disruptions.

The U.S. government has developed such a model. It plans to establish a Supply Chain Disruptions Task Force[29] led by the secretaries of Commerce, Transportation and Agriculture. It will focus on areas where there has been a mismatch between supply and demand (based on its supply chains report) and use federal policy to address near-term supply-demand mismatches including through convening stakeholders to diagnose problems and identify solutions.

Similar to the previous recommendation, this one could be pursued as a provincial initiative or in partnership with the federal government. It would also be important to have representation and engagement from key sectors.

3. Great Lakes Reshoring Initiative

The provincial government could work with neighbouring states such as Illinois, Michigan, New York and Ohio on regionalized supply chains. This could come in the form of a new bilateral institution dedicated to supporting reshoring efforts around the Great Lakes.

Ontario already has memoranda of understanding with some of these states on tourism and economic cooperation.[30] This would represent a new, more dedicated partnership on industrial cooperation in strategic or critical goods. A Great Lakes Reshoring Initiative is highly consistent with Secretary Yellen’s calls for a new “friend-shoring” model. The Ford government should pursue it.

4. Reshoring Fund

As mentioned above, any reshoring strategy must take into account the marginal cost of production, which means it will likely require public subsidies. The Ontario government might consider announcing plans for a new reshoring fund that could serve as the source of such subsidies. The magnitude of the program would be scalable – though the level of public subsidies needed for certain private sector investments (such as a new vaccine production facility) could be significant.

The program’s terms and conditions would need to be transparent. Decisions on tapping the fund would be the purview of Cabinet but could be based on the advice of a provincial supply chain task force. There may also be future opportunities to leverage federal programs so that the cost to the public treasury is shared.

Sean Speer is a Senior Fellow at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy and project co-director of Ontario 360. Sean is also the PPF Scotiabank Fellow for Strategic Competitiveness at the Public Policy Forum and editor at large at The Hub.

He previously served as a senior economic adviser in the Prime Minister’s Office.

Drew Fagan is a Professor at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy and project co-director of Ontario 360. Drew is also a senior advisor at McMillan Vantage Policy Group and a former Ontario deputy minister.

Saif Alnuweiri is an Economics and Policy Advisor in the Ontario Public Service and a graduate of the MPP program at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the University of Toronto. He has contributed previously to policy briefs and reports for ON360 and the Toronto Region Board of Trade.