Policy Papers

ON360 Transition Briefings 2022 – Attracting and Retaining Capital and Labour in Ontario’s Manufacturing Sector

This paper boldly explores how to make Ontario the best jurisdiction in North America to start or grow a manufacturing firm and what sorts of policy decision need to be made to support that goal.

Issue

Ontario’s manufacturing sector continues to flourish, despite a massive drop in manufacturing employment between 2004 and 2009 and supply-chain challenges during the pandemic.

We believe the Ontario government needs a plan to ensure prosperity in the sector. Any plan needs to start with a vision. We suggest the vision: To make Ontario the best jurisdiction in North America to start or grow a manufacturing firm. All policy decisions should be in support of that vision, and the bottlenecks to achieving that vision must be identified.

While this vision is bold, we believe it is attainable. This vision must be grounded in reality, understanding that:

- Ontario’s economy is export-dependent, and the global economy is changing. The world is headed towards net-zero emissions, and new global value chains are forming, with or without Ontario. The status quo is not an option.

- Ontario’s manufacturing sector is comprised of a set of regional clusters that specialize in a particular manufacturing industry, from aerospace to pharmaceuticals to meat processing. While there are challenges relatively common to all, from high energy prices to U.S. protectionism, each cluster also faces a specific set of opportunities and threats; detailed knowledge of each is vital.

- Creating something from nothing is not a recipe for success. Ontario must find ways to adapt, renew, and transform existing manufacturing clusters to be successful in a global economy headed towards net-zero. Any plan must be rooted in history and geography, as discussed in the report renewal and reinvention of Alberta’s hydrocarbon cluster. The plan must also be rooted in existing economic strengths, as outlined in the report Canada’s Future in a Net-Zero World.

Ontario must recognize that growing the domestic market requires a strategy to transition the economy

The manufacturing sector will thrive in an economy with a clear strategy for transitioning its component clusters to net-zero. This is vital, to hit both domestic emissions targets and to recognize that our major trading partners require products and services to hit their emissions targets, creating a 26 trillion-dollar market opportunity. Ontario needs sectoral strategies to decarbonize and develop the sectors central to its long-term economic prosperity, including the zero-emissions vehicle supply chain, steel, aluminum and cement, and agriculture and agri-food. A climate plan to reduce emissions will only succeed if tied to an industrial transition that ensures jobs and prosperity. An industrial strategy should bring together government, industry, civil society, First Nations, and research communities to develop roadmaps to build Ontario’s place in global value chains, which are already forming. Substantial emissions reduction targets need to be matched with an industrial transition that provides opportunities for workers. Providing these opportunities is not only fair but essential to ensure political support. This transition will also support growth opportunities for Ontario’s cleantech sector, which will otherwise be drawn to jurisdictions offering greater potential. Basic principles on designing this transition are, again, provided in the report Canada’s Future in a Net-Zero World.

For ideas to accelerate growth in the manufacturing sector, Ontario 360 published a brief by the Smart Prosperity Institute last year: Made in Ontario: A Provincial Manufacturing Strategy. It contains essential context and some of the ideas presented below. It is crucial that any plans, or sectoral strategies, identify the barriers and bottlenecks to growth at a regional or cluster level. These very well may differ significantly between Southwestern Ontario’s automotive cluster and energy and resource production in Northern Ontario.

In the absence of a detailed analysis on a specific cluster, we know that three common bottlenecks for Canadian cleantech, as one key example, are:

- Lack of skilled labour;

- Weak access to capital;

- Small domestic markets.

At a minimum, any plan should have components that address each of these. The following are potential policy ideas for each.

Lack of skilled labour

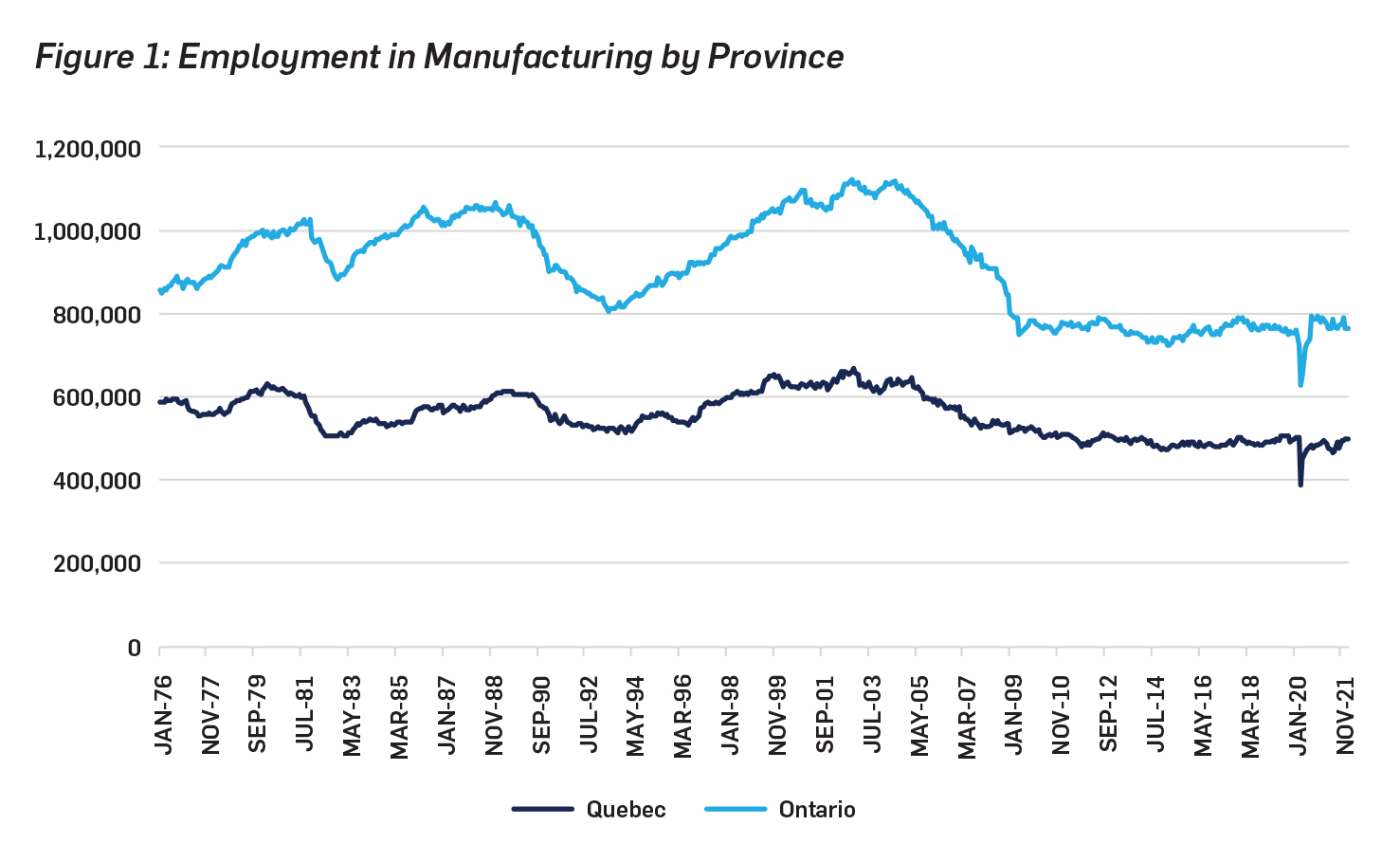

After a substantial employment decline from 2004 to 2009, the number of persons employed in the manufacturing sector in Ontario has consistently stayed between 750,000 and 800,000, outside of a dip at the beginning of the pandemic. This trend is not unique to Ontario, as employment dynamics in Quebec have shown a similar pattern.

The boom-bust cycles in Ontario manufacturing employment appear to be a thing of the past. However, the stability in the number of persons employed masks the dynamic changes occurring to manufacturing employment. Earlier in the century, much of the more labour intensive tasks in manufacturing were either offshored or automated away, leaving higher-skilled positions that require increasingly higher credentials.

Now, with increased retirements in the manufacturing sector due to population aging, eight out of ten companies in the sector are reporting skills shortages, just to keep overall employment at the current level. And with the race to net-zero requiring a host of new clean technology solutions to be developed and produced, employment levels in the sector are projected to rise, with one estimate showing an additional 163,000 manufacturing jobs to be created in Ontario over the next 30 years.

Addressing these skills gaps will prove challenging. A particular challenge will be in filling a position that requires a skilled tradesperson, as manufacturing is competing for talent with a booming construction sector. Furthermore, attracting and retaining manufacturing talent in Ontario will prove difficult due to the province’s high home prices and cost of living.

Any manufacturing labour strategy, at a minimum, should contain the following components:

- Additional research and understanding of the specific skills requirements of Ontario’s manufacturing clusters. The skills gaps in Canadian manufacturing and the future skills needed by the sector are imperfectly understood.

- Increased collaboration among industry, higher education, and government to design creative solutions to skills shortages.

- A plan to increase the employment opportunities for traditionally underrepresented groups. This must begin from a thorough understanding of the barriers and bottlenecks that limit participation, and address those at their root causes.

- A plan to lower the cost of living, particularly housing, so the manufacturing sector can attract talent from other jurisdictions and retain the workers it currently has.

Here are two specific policy recommendations that should be a part of a labour strategy for the manufacturing sector:

Skilled Labour Proposal I: Translation of successful policies from the Manufacturing USA Institute model and NextGeneration Innovation Supercluster into provincial policy will increase linkages between firm needs and academic institutions. This could help identify specific skills gaps and could inform college and university curricula, training programs, and other skills-based programs. Additional context can be found in the report Made in Ontario: A Provincial Manufacturing Strategy.

Skilled Labour Proposal II: Housing policy is essentially clean growth policy, and Ontario needs to be the most attractive place in North America for manufacturing workers to raise a family. Addressing the housing crisis will go a long way in ensuring that Ontario firms can attract and retain the workers they need. The linkages between housing and employment are detailed further in the report Priced Out and in Three reasons why housing policy is climate and clean growth policy. The recommendations of the Ontario Housing Affordability Task Force are an important first step, although additional policies on addressing the speculative demand for housing warrant consideration.

Weak access to capital

Manufacturing is an inherently capital-intensive sector, from the purchase of equipment and machinery, to conducting research and development. The need for capital is particularly acute for start-up and scale-up companies, which cannot raise capital on debt markets like more established firms. Risk capital is vital for both start-ups and scale-ups to expand operations, develop new products, and bring them to market. Bottlenecks exist across manufacturing clusters but are particularly acute for Ontario’s growing cleantech industry.

There are several policy tools that the province could utilize to increase the pool of risk capital available to Canadian manufacturing start-ups and scale-ups and attract more established manufacturing firms to set up shop in Ontario. These include:

Capital Proposal I: A reduced corporate tax rate for cleantech manufacturers. The federal government’s Budget 2021 reduced the corporate tax rates on manufacturers of zero-emissions technologies from 15% to 7.5% by introducing a new tax credit. Currently, manufacturers in Ontario are eligible for the Manufacturing and Processing Tax Credit (M&P Tax Credit) which effectively reduces their provincial corporate tax rate from 11.5% to 10%. Ontario could match the federal government’s move and halve the corporate tax rates on zero-emissions manufacturers from 10% to 5%, putting the combined corporate tax rate for manufacturers of zero-emissions products at 12.5%, which would likely be the lowest effective corporate tax rate in North America for cleantech manufacturers. This move would attract existing cleantech firms to set up shop in Ontario and attract capital to local start-ups and scale-ups due to higher returns once those firms become profitable. Additional context can be found in the report Made in Ontario: A Provincial Manufacturing Strategy.

Capital Proposal II: Investor Tax Credits (IrTCs) to attract early-stage investments. IrTCs allow a business or individual that makes an equity investment in a qualifying firm to claim that investment as a credit against personal or business income tax. This credit can help attract early-stage investment by providing a greater financial incentive, particularly to individual investors such as angel and seed funders. Currently, six provinces and one territory use IrTCs to attract early-stage capital for

a range of sectors. However, Ontario does not employ IrTCs. For additional detail, see Tax Incentives to Boost Clean Growth.

Capital Proposal III: Changes in regulations to ensure that net-zero emissions alignment is part of a pension fund’s fiduciary duties. Currently, depending on the broad or narrow interpretations of fiduciary duties, pension fund managers might not align their practices and investment strategies to achieve net-zero emissions. Concrete regulations would not only help implement the top-level goal of emissions reductions across a portfolio but also create impetus for Ontario-based pension funds to increase investment allocations towards renewable energy and cleantech manufacturing and provide capital to such companies. This reform needs to include the Financial Services Commission of Ontario, which supervises the pension funds based in Ontario (e.g., OTPP, OMERS, HOOP etc.). For details, see Canadian Pensions Dashboard for Responsible Investing.

Small domestic markets

Although Ontario has an export-dependent economy, start-ups and scale-ups will typically make their first sales locally before expanding into new markets. Canadian manufactured goods and services are in demand; however, Canada’s relatively small market and a risk-averse purchasing culture can make it difficult for domestic manufacturers to achieve the scale to go global. Some policy tools that the province can utilize to overcome these challenges include:

Market Proposal I: Support the creation of a buyers’ group for Ontario clean technology manufacturers. A buyers’ group is a group of provincial and municipal departments, as well as agencies, which come together, identify their core purchasing needs, and communicate that information to companies in the market. This model, used successfully in health technology by CANHealth, helps government better communicate its needs to the market, allows companies to learn more about prospective customers, and has proven helpful in overcoming interprovincial trade barriers to create more jobs in Ontario. This reform is detailed in the report Buying Better: Leveraging federal procurement to support more Canadian clean technology.

Market Proposal II: Put procurement rules in place that allow purchasing of goods and services to better reflect new solutions the market can provide. A pivotal barrier to procurement in Canada is that teams within government do not always have information about current solutions the market can provide to meet their needs, or do not have the technical expertise/resources needed to translate these market offerings into the language used in requests for proposals or bid requirements. Creating new rules that allow greater market communication, and having technical experts in-house, would improve government purchasing of services to be more cost efficient and effective and could ensure governments provide the best value of services for citizens. For additional context, see Buying Better: Leveraging federal procurement to support more Canadian clean technology.

Market Proposal III: Investment Tax Credits (ImTCs) to incentivize cleantech adoption. ImTCs allow firms to reduce their tax liability by an amount related to their expenditures on qualified equipment. It helps to incentivize investment in the adoption of cleantech by businesses and firms as part of their operations (e.g., Purolator investing in an electric vehicle fleet in Ontario). Tax credits will help reduce emissions across a number of sectors (e.g. transport, industries, etc.) and help overcome the real or perceived risks in utilizing cleantech, thus expanding markets in Ontario, as discussed in Taking the Tax System to Task.

Conclusion

The future is bright for Ontario’s manufacturing clusters. Although one model estimates Ontario job growth in the sector at 163,000 persons over the next 30 years, we would suggest Ontario’s potential for growth can exceed that, with the right policy environment. The jobs created in the sector are increasingly high-skill, and high-pay, and the goods created can help the province, and the world, hit their climate targets.

The vision, simply put, should be to make Ontario the best jurisdiction in North America to start or grow a manufacturing firm. To get there, we need a competitive business environment, with high quality infrastructure and availability of affordable inputs, such as energy. We also need to create a high-quality of life to attract and retain workers in the sector. This necessitates tackling Ontario’s cost-of-living challenges, particularly housing. We need an environment where every Ontarian is allowed to contribute to the sector, and benefits from the sector. And most importantly, we need business, government, labour, and higher education to work together to address the obstacles that stand in the way of achieving this shared vision.

Mike Moffatt is the Senior Director, Policy & Innovation at the Smart Prosperity Institute.

Derek Eaton is Director of Public Policy Research & Outreach, Anik Islam is Research Associate and John McNally is Senior Research Associate.

Smart Prosperity Institute is a policy think tank based at the University of Ottawa, delivering practical policies and market solutions for a stronger, cleaner economy.