Policy Papers

ON360 Transition Briefings 2022 – Doing More For Those With Less: How To Strengthen Benefits And Programs For Low-Income Individuals And Families In Ontario

Ontario’s system of supports for people with low incomes is ineffective and in need of significant improvement. Garima Talwar Kapoor provides recommendations for strengthening social assistance and broader supports for the low-income population in Ontario.

Issue

Ontario’s system of supports for people with low incomes is not reflective of today’s social, economic, and labour market realities. Ontario’s social assistance system is particularly ineffective and in need of significant improvement.

A newly elected Ontario government should make significant efforts to strengthen income supports and services for both people receiving social assistance and the broader low-income population.

Context

Overview of Ontario Works and the Ontario Disability Support Program

Ontario’s social assistance system is largely made up of two programs: Ontario Works and the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP).

Social assistance is considered to be a program of “last resort.” That is, recipients are required to meet stringent eligibility criteria to access social assistance and cannot increase their total incomes through income replacement programs like Employment Insurance. While the eligibility criteria for both social assistance programs differ depending on family type, benefits for both are deeply inadequate.

Generally, Ontario Works benefit rates are lower than ODSP benefits. Ontario Works is provided to low-income people considered “employable” (that is, they do not have an identified disability that should prevent labour market attachment), and ODSP is provided to those who are considered to have disabilities that impede active labour market attachment. It should be noted that the divide between who can and who cannot work due to disability is outdated.

Within programs, social assistance income support is split into separate payments for basic needs and shelter. For example, for a single adult receiving Ontario Works in 2022, the basic needs portion of their benefit is $343 and the shelter component is $390, for a total monthly benefit of $733.[1] People receiving social assistance are also eligible for prescription medication coverage and can receive some other support (e.g., dental coverage), depending on the program they are in and their circumstances.

Social Assistance Benefits and Labour Market Attachment

In Ontario, social assistance benefits are designed to incentivize labour market attachment. In effect, this means that income support policy is based on the idea of marginal effective tax rates (METRs) – the combined percentage of benefits and personal income taxes lost for earning an additional dollar of income – and labour market attachment. The theory is that lower benefits paired with low personal income taxes will encourage labour market attachment and lead to less reliance on social assistance. As a result, successive Ontario governments have tried to keep benefit rates low. Low benefit rates have met the twin goals of trying to “incentivize work” while also keeping fiscal investments in income support programs low.

However, Ontario’s labour market has changed structurally over the past several decades. It is therefore important to ask what kind of labour market people are being “incentivized” to join, and whether today’s low-paid work can help contribute to one’s income security and overall well-being. For example, non-standard work, which can be precarious and is defined as temporary work, self-employment, part-time, or multiple job holding, grew at twice the pace than standard work did from 1997-2015.[2] Furthermore, from 2000-2016, the median employment income of working-age families grew slowly, at an annual average rate of 0.4 per cent. However, for working-age singles living alone, median employment income declined by 0.5 per cent from 2000-2016.[3]

In relying on METRs to design income supports, policymakers often overestimate how theoretical ideas apply practically. One cannot make assessments about how people make decisions about work effort without asking whether people have control over their schedules, employment relationship dynamics, and the overall value of compensation (e.g., low-paid hourly work is often without health, protected and paid sick days, and retirement benefits).

As the economic environment and labour market have changed markedly, traditional ideas about the relationship between benefit rates, length of time of benefit receipt, and employment need to be revisited. Efforts to keep rates low have not led to quick exits out of social assistance and have instead exacerbated deep poverty.

Problem

Poverty levels

In Ontario, 10.9 per cent of people, or over 1.5 million people, lived in poverty in 2019.[4] Furthermore, about 6.5 per cent, or just under one million people, received social assistance in 2019-20.[5]

Income support levels for people receiving social assistance

The following four charts illustrate the rate and depth of poverty that people receiving social assistance face. These illustrative examples demonstrate that the level of income support provided to people receiving social assistance and without any employment earnings is deeply inadequate.

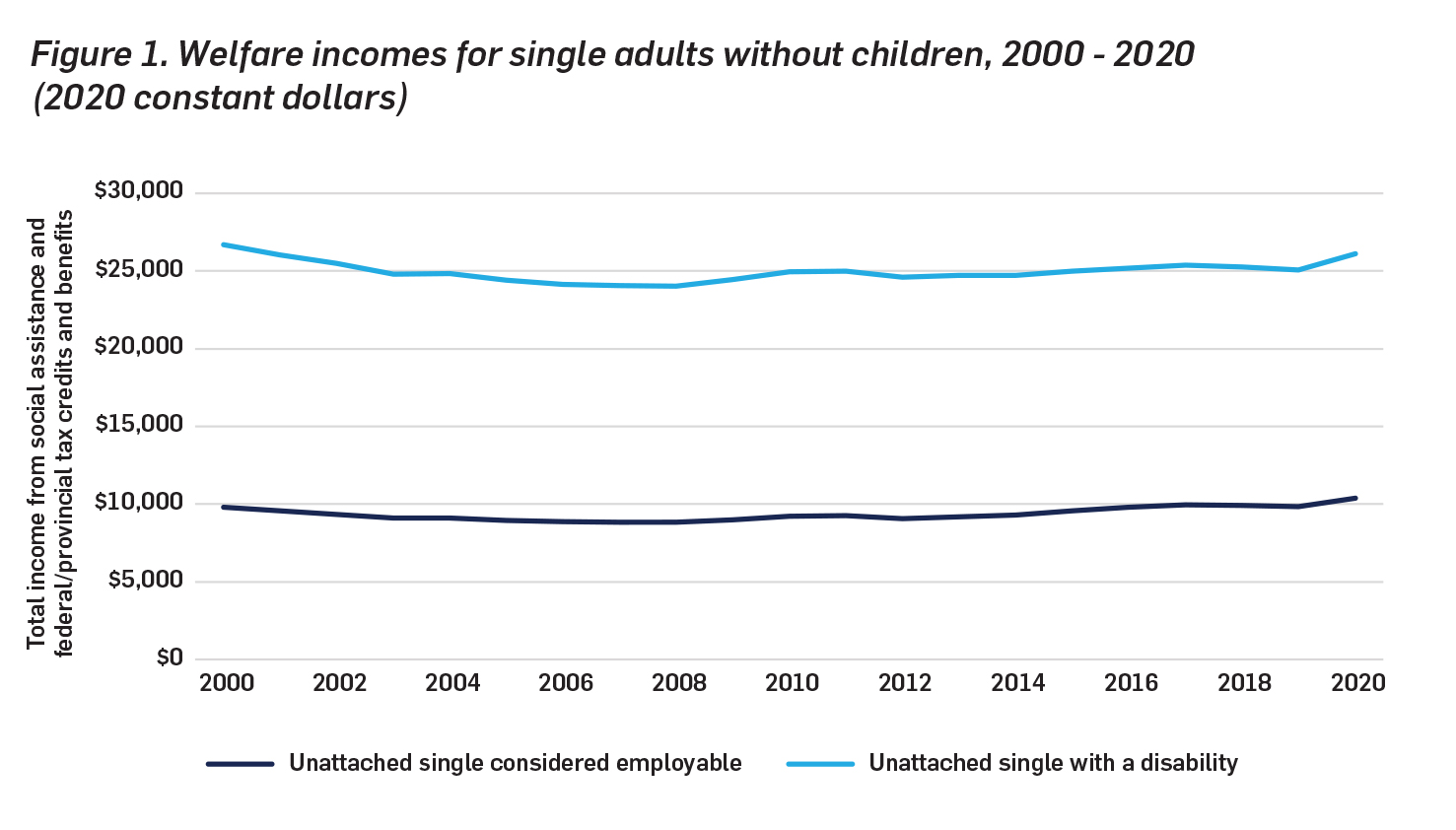

To start, figure 1 demonstrates the relative stagnation of “welfare incomes” of single unattached adults from 2000-2020. Welfare incomes include benefits from social assistance and other provincial and federal income-tested tax credits and benefits.[6] From 2000-2020, benefit rates for working-age singles receiving Ontario Works did not meaningfully change. For ODSP recipients, the benefit rate for a single adult was lower in 2020 than in 2000.[7]

Source: Laidley and Tabbara. “Welfare in Canada, 2020.” 2021. Accessed at: https://maytree.com/welfare-in-canada/

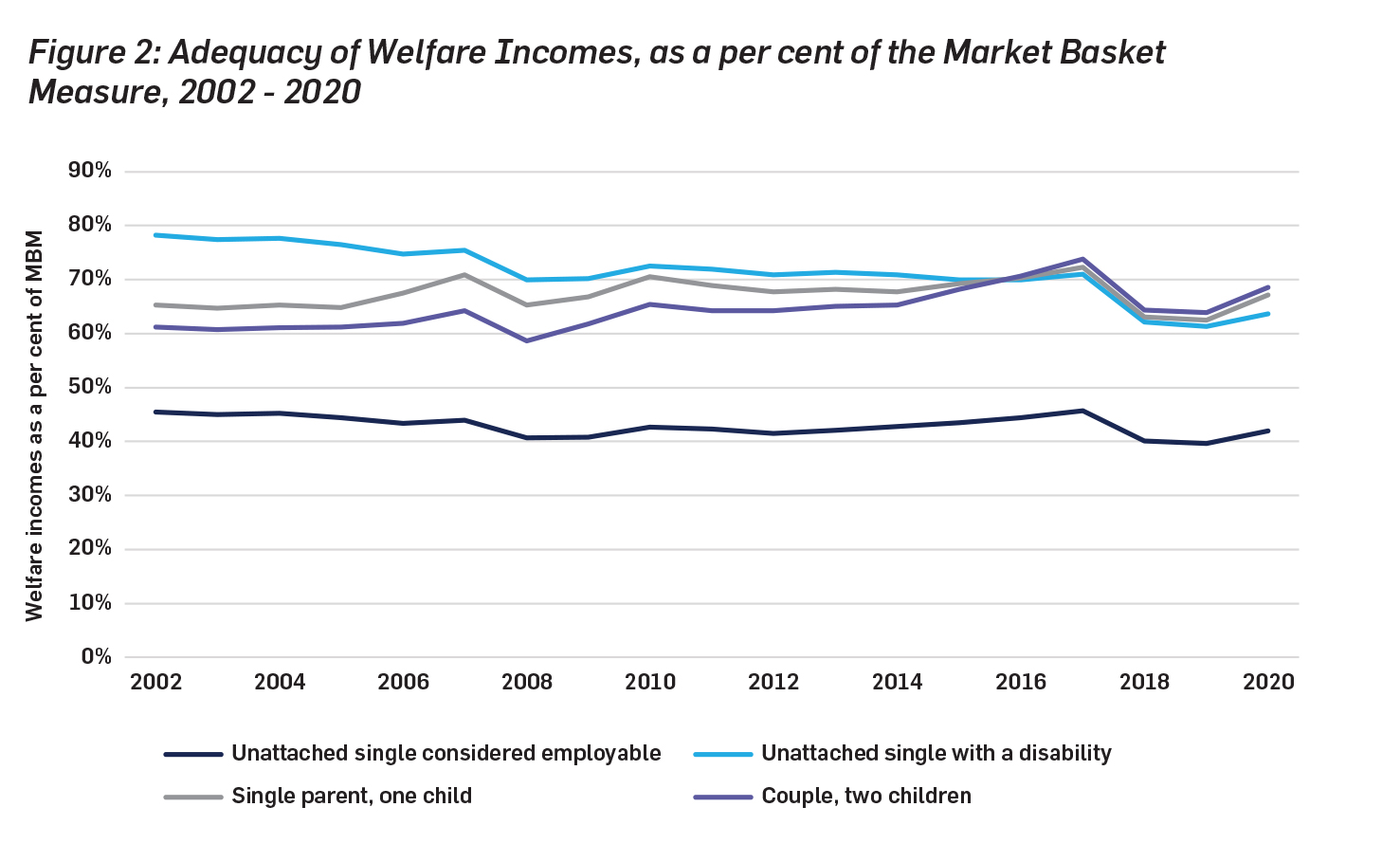

Over time, social assistance benefit rates have remained persistently inadequate given increases in the cost of living. Figure 2 illustrates the depth of poverty that social assistance recipients face by household type. This figure shows how levels of poverty tend to be related to levels of support received from social assistance benefits and income-tested tax credits and benefits. For example, poverty levels are generally lower for families with children who receive the Canada Child Benefit and the Ontario Child Benefit, two tax-based benefits that are provided to families with children whether they receive social assistance or not.

Single, unattached working-age adults receiving Ontario Works face significantly deep levels of poverty in Ontario. While it appears that single adults receiving ODSP benefits do not experience the same degree of poverty, the poverty measure used in this chart—the Market Basket Measure (MBM)—does not account for the higher cost of living that many people with disabilities face. Therefore, it is likely that the depth of poverty that this group experiences is higher than illustrated.

While benefit rates increased slightly in 2020 as a result of some COVID-19 related benefits, these benefits were not extended into 2021. It is likely that social assistance recipients will have had a decrease in their welfare incomes in 2021.

Source: Laidley and Tabbara. “Welfare in Canada, 2020.” 2021. Accessed at: https://maytree.com/welfare-in-canada/

Number and proportion of people receiving social assistance and living in poverty

The number of social assistance beneficiaries has increased in recent years. As illustrated in figure 3, this increase has been driven by the number of people receiving ODSP. In total, there were just under one million people receiving social assistance in Ontario in 2019-20.

Source: Tabbara, M. “Social Assistance Summaries.” 2021. Maytree. Accessed at: https://maytree.com/wp-content/uploads/Social_Assistance_Summaries_All_Canada.pdf

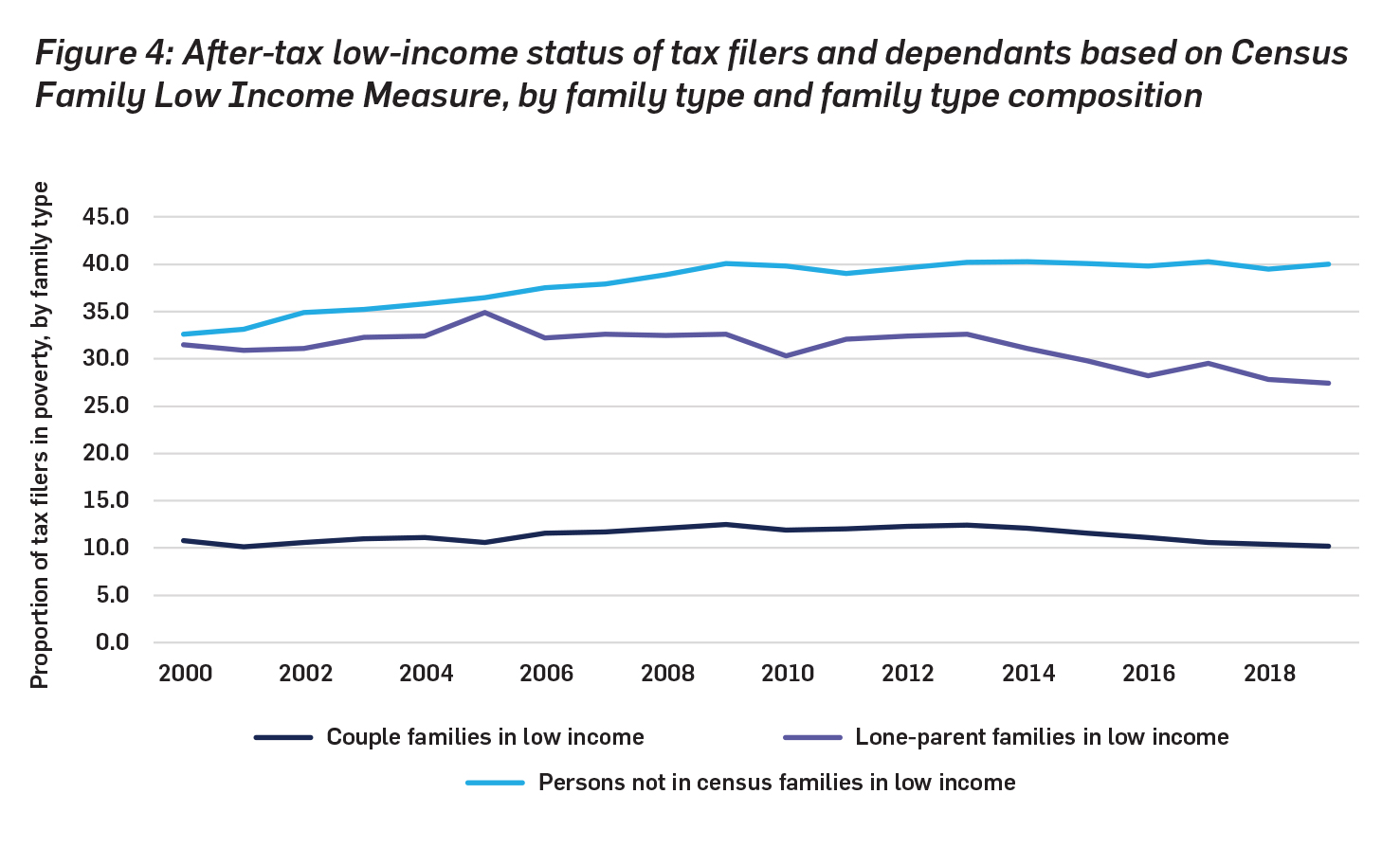

Despite economic growth over the past 20 years, poverty rates in Ontario have not abated. This is particularly the case for working-age singles. As a direct reflection of the deeply inadequate supports they receive and labour market realities, their rate of poverty has been steadily increasing. Figure 4 provides an illustration of the combined effects of the trends described above.

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 11-10-0018-01. “After-tax low-income status of tax filers and dependants based on Census Family Low Income Measure (CFLIM-AT), by family type and family type composition.” 2022. Accessed at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/cv.action?pid=1110001801

Historical underinvestment in public services reflect the rate and depth of poverty people receiving social assistance face

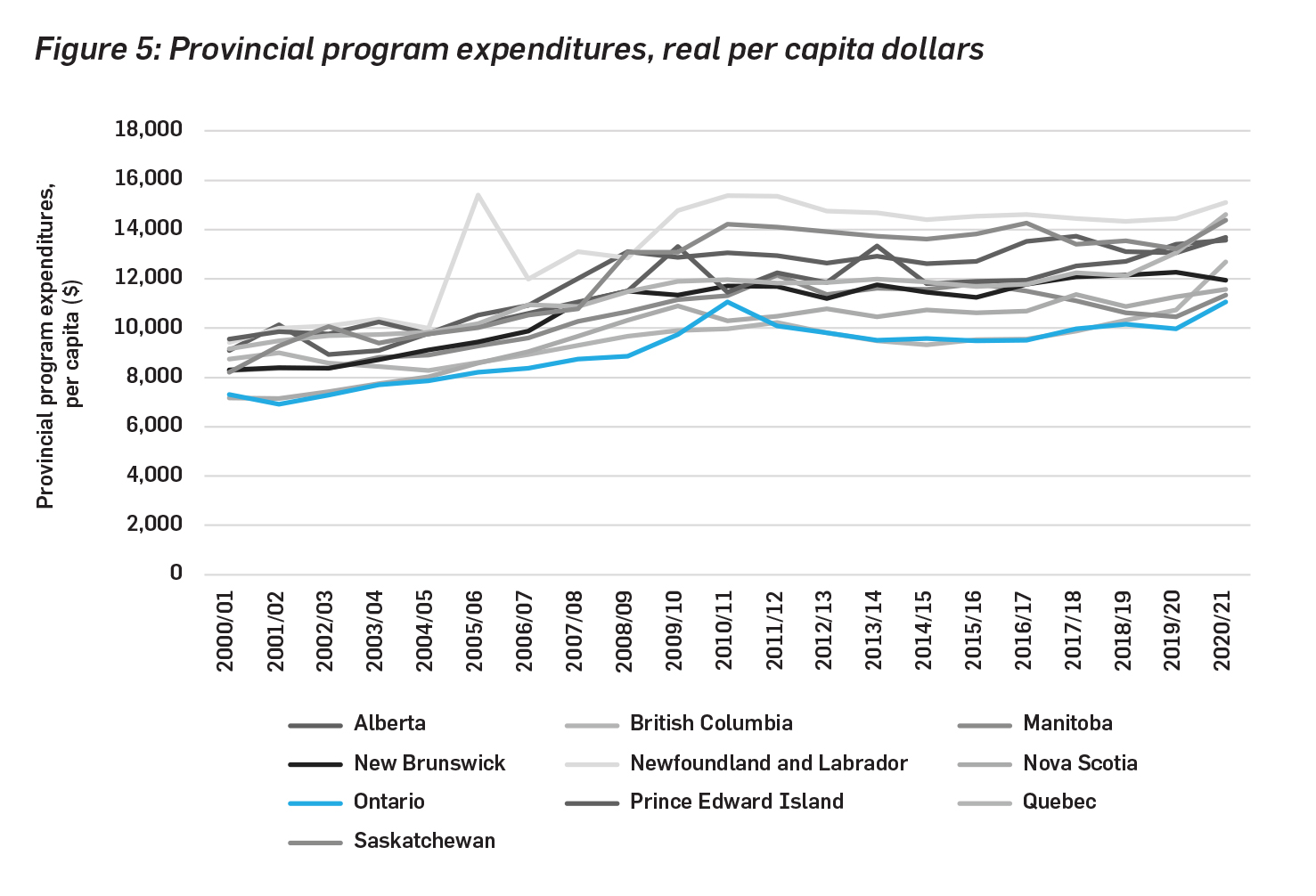

Successive Ontario governments for years pointed out that they invest the least (on a per-capita basis) in public services compared to other Canadian provinces. Given long-standing problems identified for people receiving social assistance, Ontario cannot rely on antiquated ways of thinking about how to address poverty in the province – by “incentivizing” work rather than providing additional support. See Figure 5 for a comparison of all provinces.

Source: Finances of the Nation. “Program Expenditure.” 2022. Accessed at: https://financesofthenation.ca/real-fedprov/

The Ontario government invested $9.4 billion in social assistance, or about 5.8 per cent of its total program expenditures, in 2018-19.[8] To provide more support, further investments in social assistance will be required, but they should also be complemented by enhancements in other public services that improve income security. For example, the Ontario government spent less than 0.3 per cent of its annual expenditures from 2014-15 to 2018-19 on housing and homelessness programs, at a time when the cost of housing increased significantly.[9]

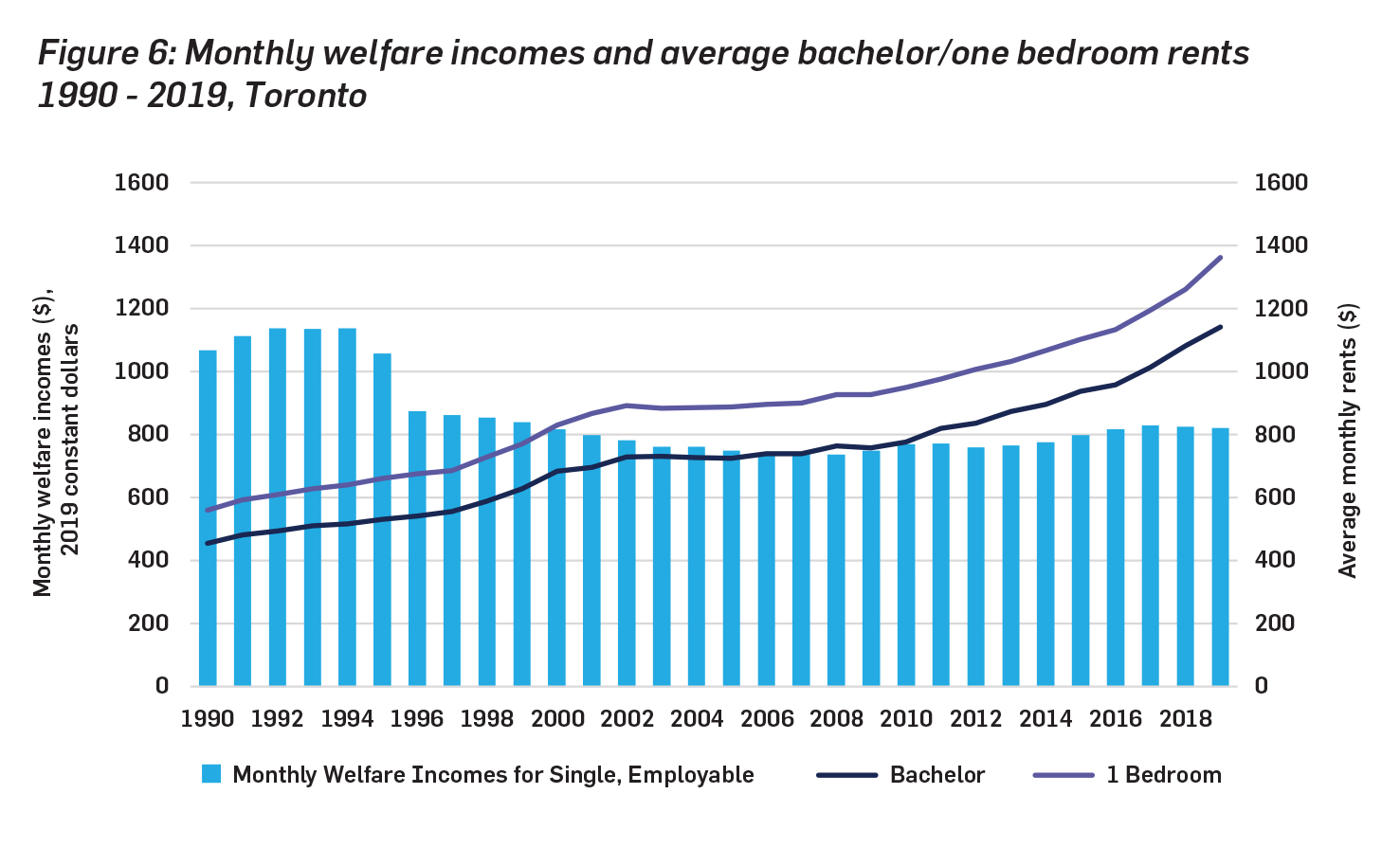

Source: Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. “Toronto – Historical Average Rents by Bedroom Type.” 2022. Accessed at: https://www03.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/hmip-pimh/en/TableMapChart/Table TableId=2.2.11&GeographyId=2270&GeographyTypeId=3&DisplayAs=Table&GeograghyName=Toronto ; and Laidley and Tabbara. “Welfare Incomes, 2020.” 2021. Accessed at: https://maytree.com/welfare-in-canada/

Over the past several decades, market rents have been increasing while social assistance benefit rates remained static. This is a considerable problem given that a majority of social assistance recipients live in private, market-rental housing, and are just as exposed to rental market dynamics as others (see figure 6 above). The monthly welfare incomes used in this chart are for a single adult receiving Ontario Works and combines the social assistance benefits (at the maximum shelter allowance rate) and income-tested tax benefits. For those who do not receive the maximum shelter allowance or income-tested tax benefits, the gap between income and monthly rents would be even greater.

Current status of social assistance transformation policy

As part of the current government’s agenda, the province is moving towards the integration of social services to help ensure that people who are distant from the labour market have access to “life stabilization” supports before they can consider effective labour market attachment. Rightly, the government has acknowledged that labour market attachment is not possible without the stabilization of some foundational factors, like housing.

The realization of this transformation process requires significant investments in public services—from increased income supports, to housing and employment supports. It will be important that municipal service providers have the resources and capacity to improve outcomes for recipients, and to ensure that these transformation processes reduce silos, not exacerbate them.

Although the government’s agenda includes the potential offloading of employment and training services to private organizations, a truly transformed vision of social assistance would re-evaluate this change. Enabling the privatization of employment and training services to reduce public expenditures, but at the potential cost of increasing silos and undermining the ability of municipalities to provide services across a continuum of care, could create more challenges for people receiving services.

Recommendations

Here are five thematic recommendations for strengthening social assistance and broader supports for the low-income population in Ontario. These recommendations should be considered together, as progress on one element alone will not significantly improve income security for low-income individuals and families in the province.

The five recommendations are rooted in the following principles:

- Human rights: Everyone in Ontario has the right to an adequate standard of living. The realization of this human right is not determined by income alone but must also take into account the system of public and community services available to help promote one’s well-being.

- Equity: Efforts to strengthen Ontario’s social assistance system should prioritize those in greatest need of support.

- Adequacy: The level of income support provided to people living in poverty is an important marker of adequate support but not the only determinant. A focus on other public support is needed, such as housing and dental care.

Recommendation 1: Increase social assistance rates

- The first step in strengthening social assistance – and providing true “life stabilization” – has to start with an increase in the benefit rates.

- Ontario Works rates are deeply inadequate and require significant enhancement.

- For example, if Ontario Works rates for a single adult had been indexed since the mid-1990s, the benefit amount would have been $1,030 per month in 2021, as opposed to the current $733 per month.

- The level of benefit and rate increases should reflect and prioritize the advice and insights from people with lived experience of poverty.

- The benefit amount available to single adults receiving Ontario Works could be augmented by federal investments in a single, working-age tax credit. See recommendation 5 for further detail.

- The provincial government should also build on the Income Security: A Roadmap for Change recommendations and develop an “Assured Income for People with Disabilities.”

- This assured income for people with disabilities should be designed to enable stacking of benefits to reach adequacy, use an income test only (instead of an asset test), and enable adjustments of benefit as in-year income fluctuates.[10]

- The level of benefit provided to people receiving ODSP should reflect and prioritize insights and advice of people living in poverty. For example, a disability advocacy group, Defend Disability, is calling for a $2,000 per month benefit for singles receiving ODSP. Annualized, this benefit amount would be just under the MBM measure for Toronto for a single person.[11] While this monthly benefit is significantly higher than current ODSP rates, how this benefit level is achieved should not only rest on ODSP, but also consider the federal government’s commitment to develop a Canada Disability Benefit. See recommendation 5 for further details.

Recommendation 2: Transform the social assistance rate structure

- The social assistance rate structure should be transformed so that there is a single benefit rate that combines the basic needs and shelter allowance (at its maximum levels).

- The separation of the basic needs and shelter allowance in social assistance does not reflect the high cost of housing in Ontario. Instead, this separation prevents people who face significant housing insecurity and homelessness from accessing the full benefit amount. People who are homeless and currently receiving social assistance support only get the basic needs portion of the benefit and not the full shelter allowance. The integration of the basic needs and shelter allowance would help improve support for those facing the deepest levels of poverty and significant housing insecurity.

- In Toronto, about 58 per cent of the unhoused population are receiving social assistance, but presumably not the full benefit rate.[12]

Recommendation 3: Increase income exemptions to enable receipt of different benefits

- Currently, people who are eligible for other income replacement benefits like Employment Insurance have their social assistance income clawed back for every dollar they receive in other supports. While these claw-backs ensure that social assistance remains the program of “last resort,” they reduce the ability of recipients to develop greater income adequacy from other benefits.

- Income exemptions for payments from Canada Pension Plan – Disability, Employment Insurance, and Workplace Safety and Insurance Board should be treated the same as earnings exemptions (i.e., a 50 cent claw-back in social assistance for every dollar in other forms of income received).

Recommendation 4: Invest in supports embedded within social assistance, and broader public services

- The current government’s plans for social assistance change can only be realized through significant investments in broader public service areas, such as affordable housing. Investments in these public services would ensure that the broader low-income population is also eligible for support, so that they do not have to receive social assistance to access these services.

- Currently, some health benefits (e.g., dental care) are discretionary for some social assistance recipients. The government should move to expand access to mandatory core health benefits to all adults receiving Ontario Works and adult children in families receiving ODSP, and add coverage for dentures for all social assistance recipients. Therefore, these benefits would be available for all recipients regardless of the municipality within which they reside.

- The Ontario government should expand existing, and introduce new, core health benefits for all low-income individuals without private health plans—whether they are working or not.

Recommendation 5: Work to strengthen federal-provincial collaboration and develop programs and benefits that leverage policy and fiscal capacity of different orders of government

- Ontario’s capacity to strengthen income supports and public services for people with low incomes can be improved through investments from the federal government. The Ontario government should work collaboratively with the

federal government to:- Develop the proposed federal Canada Disability Benefit (CDB), and ensure that the parameters of the CDB complement, not counteract, ODSP. For example, the benefit should be designed to stack on top of other income supports and should not claw back ODSP benefits.

- Develop a benefit for working-age single adults, given that they face the deepest and highest rates of poverty. This benefit could stack on top of other income tested benefits and credits (e.g., Ontario Works and the GST/HST credit). For example, an expansion of the Canada Workers Benefit could better support working-age adults, whether they are working or not.

- Enhance the Canada Social Transfer (CST). This could help all provinces and territories invest in important social policy programs like social assistance. Enhancements in the CST for social assistance programs would also augment the role that the federal government plays in improving supports for people living in poverty across Canada.

Garima Talwar Kapoor is Director of Policy and Research at Maytree, following several years working In the Ontario Public Service in the area of income security. She has a Masters of Public Health from the University of Toronto, and is currently pursuing her Doctor of Public Health also at the University of Toronto.