Policy Papers

Lands for Jobs: An Employment Lands Strategy for the Province of Ontario

Sean Speer examines various Ontario policy reforms that are aimed at improving the province’s investment climate.

Summary of Recommendations

- Conduct regularized regional reviews of the supply and demand of employment lands and enact any necessary changes to the designation of provincially-significant employment zones

- Phase-in of standardized business education tax rate across the province

- Consider eliminating provincial property taxes as part of broader reforms to intergovernmental fiscal arrangements

Introduction

As part of its “Open for Business” agenda, the Ontario government has enacted various policy reforms to improve the province’s investment climate. These reforms have come in the form of tax reductions on certain capital investments, a series of de-regulation measures, changes to the province’s apprenticeships and skills training framework, and so on. The underlying assumption is that the cumulative effect of these policy reforms will ultimately make Ontario more attractive for domestic entrepreneurs as well multinational firms to invest and grow here.

This is a key point: there are no silver bullets or panaceas to improving the province’s investment climate. A wide range of factors inform business investment decisions – including overall economic context, interest rates, taxes, labour, energy, regulatory environment, transportation networks, property rights and rule of law and even sociocultural considerations such as diversity, pluralism, and tolerance.[1] These various inputs and factors can be broadly described as a jurisdiction’s overall “business environment.” An “Open for Business” agenda will therefore necessarily touch on a wide range of policy areas.

The government has thus set about canvassing businesses, investors, and other stakeholders over the past several months to understand what parts of the province’s policy framework represent strengths with respect to the province’s business environment and what areas require further attention.

One area that is not commonly considered as a key driver of business investment but has increasingly come up in these discussions (including with the Ontario 360 project) is the combination of commercial and industrial zoning and business property taxes. C.D. Howe Institute scholar Adam Found has described these issues as “flying below the radar” because of the tendency for policymakers and observers to neglect zoning and provincial and municipal property taxes when evaluating a jurisdiction’s overall business environment.[2] Yet evidence shows that predictable and affordable access to lands for commercial and industrial development as well as low, competitive levels of business property taxation can have a significant effect on firm behaviour and even overall investment levels.[3]

It is important therefore for Ontario policymakers to evaluate the province’s land-use policies as well as its overall business property tax framework through this lens. Uncompetitive policies in these areas could harm the government’s efforts to cultivate entrepreneurship and investment in the province.

The purpose of this policy brief is to provide a primer for Ontario policymakers and the general public on this set of issues. There are five key takeaways based on the research and analysis:

- The combination of the supply of employment lands and business property tax rates is a “sleeper” factor for investment attraction and the overall business environment.

- Structural changes to our economy – the shift from a tangibles economy (such as machinery and equipment) to an intangibles economy (such as data and intellectual property) – is affecting investment patterns and industrial composition. But that does not change the overall need for employment lands especially in the Greater Golden Horseshoe region.

- The province will need to carefully monitor the regionalized effects of recent changes to the Greater Golden Horseshoe Growth Plan to ensure that they do not create an imbalance between employment and residential lands over time.

- The province’s business education taxes are an inefficient form of taxation that are unevenly applied across municipalities in Ontario. The provincial government should resume gradual changes to uniformity in business property tax rates in order to eliminate regional and local differences.

- As part of a comprehensive “Who Does What” review, the provincial government should consider options to phase out provincial property taxes altogether as part of a broader fiscal rebalancing between the province and municipalities.

The first section of the policy brief sets out the trends in business investment in Ontario. The second provides a brief primer on the relationship between employment lands and the business environment. The third describes the current intergovernmental framework for employment lands and business property taxation in Ontario. The fourth analyses best practices in some comparable jurisdictions. The final section puts forward possible policy reforms for consideration by provincial policymakers.

State of Business Investment in Ontario

Any discussion of Ontario’s business environment must start with business investment trends in Ontario. The province’s performance on business investment has been generally underwhelming for the past fifteen years or so. There are various factors behind this. Some such as the 2008-09 recession are transitory. Others such as an aging population and the transition from a tangibles economy to an intangibles one[4] are more structural. But, irrespective of the causes, the government is right to be concerned about short- and long-run business investment in the province.

The evolving nature of business investment shaped by structural changes to the economy is important to briefly unpack here. The transition from a goods-producing economy to a service-based (or even knowledge-based) economy is affecting investment patterns in Ontario and elsewhere. This is reflected in what sectors are driving business investment as well as the type of assets that are drawing investment.

Service-based sectors such as the management of companies and enterprises and information and cultural industries were among the fastest growing in Ontario with respect to average annual investment growth between 2006 and 2015.[5] Goods-based sectors such as manufacturing or wholesale trade were among the poorest performers over this period.

Even within sectors there has been a shift from investments in tangible assets (such as machinery and equipment) to intangible assets (such as data and intellectual property). A longitudinal analysis by Brookfield Institute scholars found that between 1976 and 2008, for instance, business investment in intangibles grew from 5 percent to 13 percent of Canada’s economic output and investments in tangible asset fell from 27 percent to 16 percent of output.[6]

This general backdrop is useful to understanding business investment trends in Ontario. These changes are structural and likely to continue for the foreseeable future. But that does not mean that policymakers ought to ignore goods-producing parts of the economy or business investment in tangible assets. Goods-producing industries remain major sources of income and employment particularly among workers with different levels of human capital.[7] Ontario will thus continue to need both commercial and industrial investment if it wants to create the conditions for inclusive growth.

One way to distinguish between how much of these investment trends reflect a secular decline rooted in a global shift to services versus an Ontario-specific challenge is by measuring investment per worker relative to other jurisdictions. A report by the C.D. Howe Institute estimates that, in 2019, businesses in OECD countries were investing an average of $21,000 per worker, U.S. firms were investing $26,000, and Ontario firms were investing about $10,800 (which is itself below the Canadian average of $15,000).[8] This investment gap crosses the province’s economy, but it is especially pronounced in the investment in machinery and equipment in goods-producing sectors.

Manufacturing, which is still Ontario’s third largest sectoral source of income and employment, is one example.[9] Capital investment in the province’s manufacturing sector is still below pre-recession levels even though it is now 30 percent higher than it was in 2008 in the rest of the country (see figure 1).

FIGURE 1: MANUFACTURING INVESTMENT IN ONTARIO AND THE REST OF CANADA, 2006–2017 ($BILLIONS)

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 34-10-0035-01.[10]

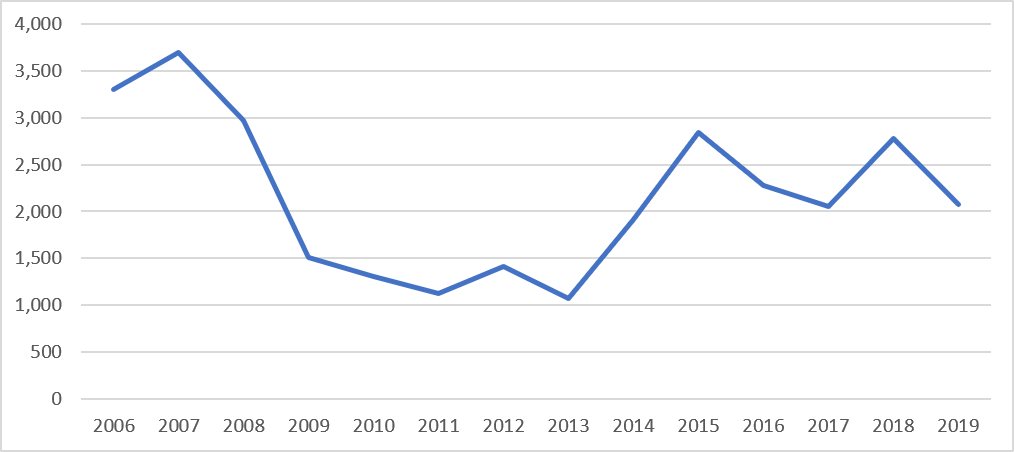

Investment in automobile manufacturing, in particular, is an example of a combination of transitory and structural trends.[11] Capital investment in the sector has ebbed and flowed a bit due to the global recession or one-off investments but the overall trend line points to a substantial gap relative to pre-recession levels (see figure 2).

FIGURE 2: AUTOMOBILE MANUFACTURING INVESTMENT IN ONTARIO, 2006-2019 ($BILLIONS)

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 34-10-0035-01.[12]

As mentioned, there are, of course, other parts of the province’s economy which have performed better. Overall investment in non-residential tangible assets is estimated to be up to 23.5 percent from pre-recession levels. It is down in five industrial sectors – manufacturing, wholesale trade, retail trade, finance and insurance, and real estate and rental and leasing[13] – and up in the other 15 sectors.[14] Yet these five sectors represent more than 45 percent of Ontario’s GDP.[15] A sustained, poor investment performance in these critical areas therefore represents a long-term threat to major sources of the province’s economic activity and access to employment and opportunity for people with different levels of human capital.

It makes sense then that the provincial government has placed an emphasis on Ontario’s business environment in order to catalyse short-term economic activity and to ensure the province is able to grow and prosper over the long-term.

Employment Lands and Business Investment

Previous Ontario 360 policy briefs and transition memos have covered a wide range of policy areas that touch on the province’s business environment.[16] These include (but are not limited to):

- Regulatory reform

- Tax policy

- Skills training and education

- Infrastructure

- Innovation

- Regional economic development

- Manufacturing

- Climate change

- Public finances

In fact, the research literature (including surveys of investors, firms, non-profit organizations, and policymakers) tells us the factors that influence business investment decisions are quite diverse and can extend far beyond narrow macroeconomic policies to include “soft factors” such as pluralism, tolerance, and political stability.[17]

Employment lands (sometimes referred to as “industrial lands” or “employment areas”) are not usually high on the list of competitiveness factors. But there is growing anecdotal and empirical evidence that they are an important consideration for business investment particularly in the areas of retail and wholesale trade and heavy manufacturing.[18]

What are employment lands?

The Ontario government’s Greater Golden Horseshoe Growth Plan defines employment lands as “areas designated in an official plan for clusters of business and economic activities, including, but not limited to, manufacturing, warehousing, offices, and associated retail and ancillary facilities.”[19]

In a nutshell, employment lands are areas that have been set aside in land-use planning for commercial or industrial development. They are therefore protected from residential development and represent a predictable supply of land that can be developed for commercial or industrial purposes.

Public policies related to employment lands can affect their supply, their market value, and the process and timelines for project approvals. Each of these areas can influence business investment decisions. Consider the site approval process for instance. Currently proposed projects can languish for indeterminate periods of time due to lengthy public consultations and inter-agency and intergovernmental reviews before the government renders decisions about site plans. Various scholars and stakeholders have argued for a streamlined process with clear timelines for consultations and public comments as well as a single point of entry and approval among provincial, regional, and local governments.[20] Analysing the timelines and process for site plan approvals is beyond the scope of this policy brief but we raise it here to emphasize that the government must think comprehensively about how its policies affect employment lands and in turn the business environment in Ontario.

The bigger point is the planning and predictability of employment lands are important for attracting and retaining investment. It has become even more so as other jurisdictions – particularly American cities – have become more strategic in their land-use policies and are now offering a mix of reliable employment lands and preferential property tax rates for firms who locate there. This does not just affect Ontario cities in a continental competition for capital and employment. Even American ones, such as Oklahoma City, have recognized that “competing cities and regions have become more aggressive in their efforts to attract companies” and that “without suitable sites, [these places are] at a competitive disadvantage.”[21]

A 2008 study on behalf of the Peel Region sought to analyse the role of employment lands in business decision-making. The report found that a combination of (i) land availability, (ii) parcel size, (iii) building configuration, (iv) proximity to customers and markets, (v) transportation infrastructure, and (vi) labour supply were the most important location-relevant factors for businesses in the initial stage of location selection.[22] But it also found that (vii) highway access, (viii) land cost, (ix) road congestion, and (x) ultimately property tax rates were high priorities in making final decisions.

These findings are intuitive but that does not make them simple for policymakers to respond to. The challenge is that provincial and local policymakers are balancing competing priorities. The primary obstacle to proper planning for employment lands, for instance, is typically encroachment caused by sprawling residential development. The City of Toronto is a good example. One analysis finds that, between 2006 and 2018, the amount of land zoned for employment purposes in the city shrunk from 8,941 hectares to 8,063 hectares which represents nearly a 10-percent reduction.[23]

These zoning choices reflect growing public pressure to address the city’s housing affordability challenges. We would be remiss, for instance, if we did not observe that a previous Ontario 360 transition memo advanced the case for increasing the province’s market-based housing supply.[24] Yet these policy choices are not without trade-offs. As progressive economist Jim Stanford has written: “[this] jeopardizes the sustainability of manufacturing, warehousing, and other industrial uses.”[25]

This trend is exacerbated by the relative value of residential real estate in the Greater Golden Horseshoe in general and the City of Toronto in particular. High residential values are enabling developers to regularly outbid industrial uses.[26] The upshot is the market is pushing in the direction of more residential use at the expense of industrial use. This can be viewed as a case of “market failure” whereby without proper government intervention in the form of adequate zoning protections for employment lands we will end up with less of it than we need or want to sustain an industrial base in the region.

The point here is that these are both important and yet not easy questions for Ontario policymakers. The evidence seems clear that predictable and affordable access to employment lands is a key factor in influencing business investment decisions. Yet at the same time governments are facing pressure to liberalize the rules with respect to market-based housing supply. Developing a policy framework that enables regional and local governments to manage these trade-offs is key to supporting the dual objectives of housing affordability and higher levels of business investment. Urban planning experts call this balance between employment and residential lands as building “complete communities.”[27]

Provincial and Municipal Roles in the Business Environment

A recent Ontario 360 policy brief highlighted the extent to which the provincial government and Ontario municipalities are intertwined in various policy areas.[28] The business environment is no exception.

The provincial government is generally responsible for setting key parts of the province’s policy framework related to the business environment. It has significant responsibilities for taxation, training, transportation, public infrastructure, and so on. It also plays a key role in establishing a framework for land use and property taxation by regional and local governments.

A Place to Grow and Employment Lands

The provincial government touches on issues related to “employment lands” or “employment areas” through instruments such as the Planning Act, the Provincial Policy Statement, and the Greater Golden Horseshoe Growth Plan.[29]

The province sets the policy framework and then municipalities are responsible for implementing regional and local zoning decisions that conform to the provincial parameters. Generally speaking, this combination of provincial statutes, regulations, and guidelines outlines expectations for municipal policy choices with respect to density, transportation, zoning decisions, and so on.

One example is the process for the conversion of employment lands to non-employment lands. Municipalities were up until recently required to apply to the province to convert employment lands to non-employment uses as part of their regularized municipal comprehensive reviews. The province’s planning framework prescribed the process and considerations for these land-use decisions.

These parameters have evolved based on public priorities and the policy and political preferences of the provincial government. The first Greater Golden Horseshoe Growth Plan prioritized density and environmental considerations.[30] It was recently updated by the current government to place a renewed emphasis on increased housing supply and protection of employment lands. As part of this renewal effort, the government released a new planning document entitled, A Place to Grow, in May 2019 to provide a framework for municipal decisions with respect to commercial and residential zoning, transportation policy, and environmental considerations.[31]

The new framework places a significant priority on housing supply that reflects the government’s Housing Supply Action Plan and a general emphasis on addressing affordability through greater supply. But it also has important implications for employment lands including the following:

- A new policy that permits municipalities to convert employment land to residential land outside of a municipal comprehensive review

- The introduction of “provincially-significant employment zones” (described in more detail below)

- Establishment of new density targets for employment and residential lands

The issue of density targets – which represent limits on the extent to which a municipality can expand its urban growth boundary into new greenfield land in terms of both jobs and number of residents per hectare – is an important piece of the puzzle here. There are some urban policy experts consulted as part of this policy brief who would argue that these targets are still too high even after the current government’s reforms and are ultimately responsible for the shortage of lands that apply to both business and residential investment.

Consider the density targets for greenfield investment for instance. The Greater Golden Horseshoe Growth Plan has required a minimum density of 50 residents plus jobs per hectare measured across a municipality’s total designated greenfield area.[32] The government has made adjustments to the target but it is still not clear that employment-based targets are even appropriate in light of the structural economic changes described earlier. Retail and wholesale trade as well as advanced manufacturing is far more land- and capital-intensive than labour-intensive in the modern economy. These types of investment may be highly valuable in the form of well-paid, highly-productive jobs but they are just not going to have the employment footprint of more traditional industrial investments. The province’s density targets for greenfield investment should therefore be re-evaluated based on Ontario’s evolving industrial model and a determination should made about possible adjustments. As a basic observation, it seems counterproductive for the provincial government to restrict municipalities’ ability to designate employment lands based on an outdated conception of the Ontario economy. An analysis of the province’s new density targets and their role in land-use decisions is significant enough to justify a future Ontario 360 policy brief on its own.

The first and second changes though are interlinked. The former makes it easier for municipalities to unlock previously-zoned employment lands for residential development. The latter creates a new designation of “provincially significant employment zones”, identified by the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing, that will still not be eligible for conversion to non-employment use outside of a municipal comprehensive review.[33]

These have come to be described as “no-touch” zones that will be protected for business and industrial investment due to their strategic value as employment lands. There are now 29 areas under the provincially significant employment zones designation.[34] The designation means that while the process for converting employment lands to non-employment use has become generally liberalized across the province, these designated zones will remain subjected to the a more stringent process for land-use conversion. The new growth plan has therefore, in effect, established a two-tier system for employment lands to build stronger protections around these provincially-significant employment zones.

One analysis of the new designation framework for the City of Toronto finds that 33 percent of the current city’s employment lands would not fall within the provincially-significant employment zones designation and thus are eligible for conversion under the new, streamlined process.[35] It does not mean that municipalities must convert these employment lands to residential use but by liberalizing the process there is potential that the market pushes in this direction.

Some have thus criticized the decision for putting the city’s employment lands at risk. Others have argued that the city’s changing industrial composition (namely the structural shift described above) means that protecting large swaths of industrial lands is no longer necessary especially in light of ongoing housing affordability challenges.

More generally, these mix of land-use changes represented in the revisions to the Greater Golden Horseshoe Growth Plan have not seemingly generated considerable public attention to date. They have mostly been the subject of attention among regional and municipal policymakers, developers, and other relevant stakeholders. To the extent that they have been the subject of political debate, it is been primarily about the potential risks of further residential sprawl rather than the effects on industrial development and investment attraction.[36]

But that does not mean that these changes are insignificant. It is still too early to understand their effects on industrial zoning in general and Ontario’s business environment in particular. It is fair to assume, however, that they will affect the province’s overall “Open for Business” agenda. We will discuss them in a subsequent section.

Business Property Taxes

A related policy area is business property taxation. It is similarly an intergovernmental file that involves a combination of a provincial and municipal policies. Both levels of government impose property taxes on commercial and industrial businesses in Ontario. Employment lands are in this sense a major source of revenues for the province and its municipalities.

The Ontario government established a provincial property tax in 1998 when it assumed responsibility for funding primary and secondary education. In so doing it inherited from local school boards a tax regime that imposed property taxes on businesses and residences as a dedicated revenue stream for education. In effect, the province’s assumption of responsibility for local education financing was combined with absorption of education-oriented property taxes on businesses and residences.

Because these property taxes were previously administered at the local level, they were set at different rates across the province. The provincial government immediately harmonized the residential property tax to a single rate across the province. It started to follow suit with business property tax rates (often referred to as “business education taxes”) with a series of reductions between 1998 and 2002 and again between 2007 and 2014 that focused on where they were the highest rates.[37] The purpose of these changes was to compress the gap between the highest and lowest business education tax rates across Ontario municipalities. But these efforts were suspended due to fiscal considerations and have not since resumed.

The result is that there remains a considerable differentiation between Ontario municipalities with respect to the province’s business education taxes. As C.D. Howe Institute scholar Adam Found puts it: “This variation comes at an economic cost, since investment decisions are distorted towards some localities or property classes (commercial or industrial) as a result.”[38]

This is difficult to justify considering the link to actual education funding is tenuous. School boards receive a combination of education-based property taxes collected in their jurisdiction (which represents about one-third of the funding source) and a top-up grant based on a formula (which represents the other two-thirds).[39] As Found writes: “the presence of the top-up grant means each board’s spending is independent of the education tax revenue raised in its jurisdiction.”[40] This means in practice that businesses in municipalities with higher business education taxes face higher tax rates without commensurate local benefits.[41]

The level of provincial-based property taxes in general and business education taxes in particular is significant. It is not just the province that imposes business property taxes either. Municipalities do too. A two-year old study by the C.D. Howe Institute, for instance, showed that in 2015 the province generated $3.8 billion in property tax revenues from businesses and municipalities raised another $5 billion.[42] That is nearly $9 billion in property taxes collected by Ontario businesses. Research finds that businesses in the province can face property tax rates that are as high as six times residential rates.[43]

It is important to observe here that it is not just the differentiation among places or the gap between residential rates that is problematic. These are not even the main objections to the current model. The real issue is that property taxes, unlike corporate income taxes, are insensitive to profits and in turn can impose considerable efficiency costs. Business education taxes basically function like a tax on investment. One estimate, in fact, finds that business property taxation represents as much as half of the total tax burden on new business investment in some cities.[44] This is a key policy insight given a large body of tax policy evidence tells us that the economic costs of this form of taxation are significant.[45]

It only reinforces that this is a substantial and yet costly form of business taxation. To put it in perspective: the province raised about $10 billion in corporate taxes in 2015.[46] It has since grown to an estimated $16 billion which means that province’s business education taxes are the equivalent of adding nearly three-percentage points to the province’s corporate tax rate. One could argue that business education taxes indirectly impose a higher corporate tax burden in Ontario but one that targets investment instead of profits.

The province cannot merely blame the municipalities here either. Remember it is generating more than nearly $4 billion in business education taxes each year and imposing differentiated rates among municipalities that are merely a function of historical anomalies. C.D. Howe Institute scholar Found (and a co-author) calls it “arguably the most inequitable provincial tax in Canada” due to its multiple rates and loose relationship with actual education spending.[47]

What makes it even more perverse is that the province’s tax industrial tax rates are even higher than the commercial rates.[48] This distortion pushes against the government’s priority to attract industrial investment such as manufacturing to the province and artificially reinforces the broader market trend towards a service-based economy. The highest tax rates on industrial properties are across Southwestern Ontario which, as economist Mike Moffatt has shown, has sustained significant job losses in the manufacturing sector over the past 15 years or so.[49]

Business education taxes have been the subject of various studies and reviews over the years. A 1998 report by a government-appointed panel recommended in favour of a “single province-wide uniform rate applied to a broad base with few exemptions [that] would be fair, clear and simple.”[50] Other, more recent reports and commentaries have made similar arguments.[51] The Commission on the Reform of Ontario’s Public Services (Drummond Commission) observed in 2012 that: “The variance in BET rates distorts efficient business location decisions and places many businesses in the province at a disadvantage, therefore having a negative impact on jobs and the provincial economy overall … [and that] Ideally, a provincial tax rate would be the same across all regions of the province, similar to the provincial uniform rate for residential properties.”[52] And even the 2008 budget observed that “The variation in rates distorts efficient business location decisions, placing many regions of the province at a disadvantage and harming the provincial economy.”[53]

As a rule-of-thumb exercise, Found (and his co-author) have sought to estimate the revenue loss from moving to a uniform business education tax rate across the province. Their analysis assumes that the rate would be consolidated to reflect the current lowest rate. Ostensibly though the government could achieve parity by moving some municipalities up and others down and striking a compromise somewhere in the middle. But still Found’s estimate is a useful measure for judging the costs and benefits of reform. Him and his co-author estimate that lowering the ceiling rate across the province to a standardized one would cost approximately $954 million or roughly 25 percent of current business tax revenues.[54] Research from economist Michael Smart suggests that such a policy change would have positive economic effects on employment and business productivity.[55]

The fiscal costs may deter the government from moving in this direction especially in light of its efforts to eliminate the province’s budgetary deficit. Moving to a single rate across the province may not be feasible from a fiscal perspective in the short-term. But it is notable then that the province’s Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review affirmed the government’s commitment to improve the business property taxation system in order to “support a competitive business environment.”[56] Subsequent sections will consider the government’s policy options.

Remember though that municipal governments also play a role here. Municipalities set the rates for the other portion of the property tax based on budget and service delivery requirements specific to each municipality. They have some flexibility from the province to set commercial and industrial property tax rates in their own jurisdiction. This can produce a degree of variation across the province based on the size of the tax base, the level of public spending, and political preferences.

It can also create some perverse political economy incentives as well. The literature, for instance, points to the potential for municipal officials to raise commercial property tax rates in order to minimize the tax burden on voters.[57] This is one of the reasons that there is a consistent gap between residential and non-residential property tax rates across the country. Another perverse incentive is the potential for municipalities to raise taxes, development charges, and other fees after a business investment is “landed” and is, for all intents and purposes, captive. This type of practice can harm long-term perceptions about a municipality’s investment attractiveness. These incentives for local policymakers can be in conflict with broader economic development goals and counteract other provincial and municipal efforts to improve Ontario’s business environment.

There is also the role of development charges outside of the municipal property tax regime. These charges, which are governed by the Development Charges Act, are supposed to help municipalities recover growth-related capital costs from new developments. It is beyond the scope of this policy brief, but we recognize the role of development charges here as part of the broader set of costs that businesses located in the province may face. There is a risk that a failure to see these questions as part of broader efforts to improve Ontario’s business environment.

It is important therefore that policymakers at both levels of government are cognizant of how their zoning and taxation choices affect the province’s ability to attract investment. If there is one major takeaway of this research, it is the need to think holistically on how individual policy choices add up to affect the business environment. Everything from zoning to property taxes to site approval timelines to development charges ultimately influence business investment decisions. This is particularly true in light of heightened efforts by state-level and city governments in the United States and elsewhere to improve their business environments and in turn their capacity to attract industrial investment.

Lessons From Elsewhere

A review of policies and practices in other jurisdictions may not necessarily provide huge surprises for Ontario policymakers. But it is still valuable to keep in mind as the provincial government advances its “Open for Business” agenda.

The first is that several U.S. states such as South Carolina, Tennessee, and Ohio have developed comprehensive strategies for attracting foreign direct investment. These strategies involve a combination of employment lands, tax preferences, direct subsidies, and more, to enhance their attractiveness as investment destinations.[58] They also involve mechanisms for intergovernmental cooperation (such as joint policy planning committees) in order to harmonize policies and take advantage of real-time opportunities.[59]

The province’s Invest in Ontario model provides firms with support with respect to greenfield investments, including site selection services, confidential property searches, and permitting and approvals coordination. Its “Investment Ready: Certified Site Program”, in particular, provides comprehensive and complete information about pre-qualified industrial properties.

There is scope, however, to ensure that its engagement and expertise is better incorporated into the Ontario government’s process for designating provincially-significant employment zones. In particular, manufacturing policy experts Paul Boothe and David Moloney have argued in favour of provinces assuming intergovernmental responsibility to act as a “single window concierge” on behalf of all levels of government in Canada.[60] This could not only better support firms that are considering investments in the province, but it could better inform provincial policymaking based on real-world experiences with successful and unsuccessful attempts to secure investment in the province.

The second is that several U.S. cities have opted to prioritize the protection of employment lands in their land-use planning. In fact, a 2017 study found that 12 of the country’s largest cities had passed new land-use designations to protect industrial land from conversion to non-industrial uses in order to stem industrial job losses and maintain strategic reserves of employment lands.[61] The report examines the different experiences and policies in cities ranging from Baltimore to New York City to Seattle. The author describes this trend as “a transformation in the way that city planners understand the role that industry and manufacturing play in their cities as well as the rejection of the selective application of “highest and best use” economic reasoning that justifies the conversion of scarce industrial land.”

These U.S. cities are in effect opting to tilt their policy frameworks in favour of employment lands. The trade-offs are challenging especially in light of ongoing housing affordability challenges in the Greater Golden Horseshoe. But it is important that provincial and municipal policymakers evaluate them as part of their own zoning decisions. Establishing a regularized regional process for assessing supply and demand of employment lands can help to ensure that the Greater Golden Horseshoe region has the right quantity and locations designated for industrial use in order to compete with these other jurisdictions for industrial investment. As part of such an exercise, the government’s demand forecasts should be realistic yet ambitious. The goal is to ostensibly attract industrial investment after all. Weak demand forecasts would merely affirm the status quo or even lead to further conversions to non-employment land use.

The final is that several U.S. states and cities provide for generally low or preferential property tax rates for new investment.[62] Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee, for instance, offer various forms of property tax abatements that can generally range from 5 years to 20 years.[63] A 2013 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston estimated that the total value of the property tax incentives alone totalled somewhere between $5 and $10 billion annually across the U.S.[64]

What is interesting is the study found that every U.S. state permitted some form of property tax incentives for businesses. Currently Ontario municipalities face constraints on their ability to provide preferential rates or tax abatements for businesses or new investment. The one exception is Tax Increment Equivalent Grants whereby a tax increment (part or all of the annual tax increase over a specified period) is returned to businesses as a grant. But otherwise there is limited scope for municipalities to use other policy instruments as business incentives. It is not clear that the province should go down this road. A 2008 literature review by municipal policy expert, Enid Slack, for instance, reached mixed conclusions.[65] A previous Ontario 360 policy brief considered the use of regionalized or local tax-based incentives to support investment in rural and economically-distressed communities in the province.[66]

But the point is that competing jurisdictions are offering low-tax options (in the form of low basic rates and incentives) to businesses as part of their investment attraction strategies and the provincial and municipal governments here need to be cognizant of Ontario’s mix of property taxes, development charges, and other fees and how it compares. The province’s overall business property tax regime cannot be set in isolation.

These three insights from the policies and strategies in competing jurisdictions can help to inform policy reforms here in the Province of Ontario. It is not that provincial and municipal governments need to copy what these states and cities are doing. Remember the competitiveness of one’s business environment is the aggregation of various policies and circumstances. The key though is that policymaking is intentional, deliberate, and ultimately rooted in the evidence including a scan of what jurisdictions are doing to improve their own business environments.

Policy Recommendations to Improve Ontario’s Business Environment

Thus far this policy brief has sought to draw attention to the role that predictable and affordable employment lands can play in business investment decisions and to provide a primer on the evolution of Ontario’s policy framework and some of the inherent trade-offs that policymakers must think about in this policy area.

There are no simple answers here. Tensions between economic development goals and housing affordability objectives, for instance, will require ongoing and careful adjustments.

Anticipating broader industrial trends is also challenging. It is true that Ontario’s economy will likely continue to shift in the direction of service-based industries. But that does not mean the government should abandon the goal of goods-producing sectors such as manufacturing given their disproportionate roles in income and employment particularly for Ontarians with different levels of human capital. The upshot is that policymakers will need to root their decisions in a clear strategy and the best evidence and make adjustments accordingly.

Our research points to three policy recommendations for Ontario policymakers. It is worth elaborating on them in sequence.

- Conduct regularized regional reviews of the supply and demand of employment lands and enact any necessary changes to the designation of provincially-significant employment zones

We do not fully know the impact of the government’s reforms to the Greater Golden Horseshoe Growth Plan’s treatment of employment lands, including liberalizing the conversion of employment lands to residential use and creating 29 provincially-significant employment zones.

These changes may make sense over the long-term or they may create an imbalance between employment and residential lands in the Greater Golden Horseshoe that could become an impediment to investment attraction and economic output.

This policy brief has sought to show that the answer to this question could matter a great deal for the province. It is important therefore that the province tracks the impact of these policy changes and makes ongoing adjustments.

The new growth plan enables the government to “review and update provincially significant employment zones.”[67] It should establish a regularized review process that evaluates the supply and demand of employment lands on a regionalized basis. The key here is ensure that the region (as opposed to any single municipality in isolation) is achieving the right balance between employment and residential lands to reflect economic trends and industrial demands.

The review process should be principle-based and transparent so as to minimize political horse-trading or other non-evidentiary factors. The right timeline for such a review is probably every one to three years. The results should be made public and any changes to current or new provincially-significant employment zones should be enacted immediately thereafter.

2. Phase-in of standardized business education tax rate across the province

As described above, business education taxes are an inefficient form of taxation and are unevenly applied across the region and province. Previous efforts to shift to a single rate have been superseded by fiscal considerations.

Establishing a single rate would address inequities and reduce the distortions caused by the provincial property tax. Targeting the lowest urban rate (0.92 percent in Halton) would, according to one estimate, lower provincial revenues by roughly $954 million per year.[68]

That may be too costly for the provincial government in the short-term due to its fiscal priorities. But it should still renew a gradual, multi-year plan to establish a single rate for business education taxes across the province.

The economic case here is important. The literature tells us that taxes on capital are among the least efficient means of raising revenues for governments. One estimate, for instance, finds that at the average level of business property taxation in Ontario, a $1.00 business property tax hike costs the Ontario economy $5.56.[69]

In hindsight it might have been useful to evaluate whether reforms to business education taxes would have been “better bang for the buck” than Ontario government’s Ontario Job Creation Investment Incentive which provided tax relief for various types of capital investment. It is possible the former may have had a greater impact on lowering marginal effective tax rates in the province.

Either way, the Ontario government should resume progress on moving to a standard rate for business education taxes and in so doing achieving greater equity and reduce distortions across the Greater Golden Horseshoe and elsewhere in the province.

3. Consider eliminating provincial property taxes as part of broader reforms to intergovernmental fiscal arrangements

A previous Ontario 360 policy brief has recommended that the Ontario government conduct a “Who Does What” review to bring greater rationality to the relationship between the provincial government and municipalities. The goal of this review would be to enhance efficiency in public spending and improve service delivery for Ontarians. As part of such an exercise, the Ontario government should consider ceding the property tax space altogether.

The case for eliminating provincial property taxes rests on a few arguments including:

- It would increase transparency and accountability for businesses and households because now a single level of government would be responsible for the entire property tax bill. If some municipalities want to impose higher property tax rates than others, then they would be responsible for benefits and costs of that choice and vice versa. But ratepayers would now have a clearer sense of which government is making these decisions and would be better able to hold it accountable.

- It would help to address fiscal capacity challenges for municipalities and, according to a policy paper published by the Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance, would mean that municipalities have more tax room to meet expenditure needs and in turn could rely less on the province.[70]

- A new, major revenue capacity for municipalities may be used by the province to negotiate other policy changes that would minimize the incentives for municipalities to impose high costs on investment. These might include: an expectation that municipalities close the property tax rate gap between businesses and households or refrain from imposing incremental costs on firms after they have invested in a community. These changes would help to improve the province’s overall business environment. This is a key point: Shifting this fiscal capacity to municipalities might be accompanied by clear parameters for municipal rate-setting to ensure that property tax rates across the province remain consistent with the government’s “Open for Business” objectives.

We recognize that this is an ambitious reform. The province generates more than $6 billion per year in property tax revenues. It would amount therefore to a significant intergovernmental transfer if the government eliminated them in order to permit municipalities to assume this fiscal room. But if it was part of a broader set of intergovernmental reforms (including clarifying service delivery responsibilities and changing current transfer payments), the net costs for the province could be reduced.

Conclusion

This policy brief has analysed the role of employment lands and business property taxes on Ontario’s overall business environment. The combination of these policy areas represents a “sleeper issue” for the province. The evidence shows that predictable and affordable employment lands can influence business investment decisions particularly in certain sectors such as retail and wholesale trade and manufacturing.

Queen’s Park has recently reformed the Greater Golden Horseshoe Growth Plan to rebalance the employment lands/residential lands designation – including generally liberalizing the process to convert employment lands for residential use as well as designating 29 provincially significant employment zones that will be subjected to more restrictions for conversion. These reforms have been shaped in part by the need to respond to the region’s housing affordability crisis and in part due to evolving structural changes to the province’s economy.

This may well make sense from both perspectives. But it is critical that the province tracks the impact of these policy changes on a regional basis to ensure that the government is striking the right balance for the Greater Golden Horseshoe.

The current tax treatment of these employment lands is also creating a disincentive for investment. Provincial property taxes are in significant in terms of overall business taxes in the province particularly on new investment and are the worst kind of tax because they are not profit sensitive. That they are not applied consistently across the region or province only produces greater distortions. The Ontario government should therefore resume the gradual changes to business property tax rates in order to eliminate regional and local differences and even consider options to phase them out altogether as part of a broader fiscal rebalancing between the provincial government and municipalities.

These policy reforms can be part of ongoing improvements to the province’s policy framework with respect to employment lands as well as business property taxation in the name of strengthening Ontario’s overall business environment.

Author Bio

Sean Speer is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy.