Policy Papers

In It Together: Clarifying Provincial-Municipal Responsibilities in Ontario

The Province of Ontario and its municipalities should review the current division of responsibilities for planning, regulating, funding, and delivering key services to Ontarians.

Summary of Recommendations

The Province of Ontario and its municipalities should review the current division of responsibilities for planning, regulating, funding, and delivering key services to Ontarians. Such a review should focus on safeguarding accountability, sharing costs fairly, enhancing quality of service, and ensuring effective and efficient service delivery. The following six recommendations should guide the review:

- Take a collaborative approach: A top-down approach will not produce the best results for Ontarians. Instead, the provincial government should take a collaborative approach, engaging municipalities, Indigenous communities, the business community, and service providers as partners in the process to promote service innovation and ensure greater buy-in.

- Follow the pay-for-say principle and avoid unfunded mandates: A government’s input into how a service functions should be matched with a corresponding responsibility to pay for that service. Unfunded mandates, whereby provincial regulations require local government to perform certain actions without providing money to meet those requirements, should be avoided. In cases where shared funding or responsibility is deemed the best option, agreements with clear and distinct responsibilities, as well as procedures for resolving conflicts, are essential.

- Consider local revenue capacity: Any proposal to increase municipal service responsibilities should consider whether local governments have the necessary and appropriate resources to meet these responsibilities. A review should look at municipalities’ ability to pay and whether they have the right sources of revenue to pay for the new municipal responsibilities.

- Respect local and regional differences: The costs of delivering services are not the same across the province. A review should analyze costs on a per-capita basis and take into consideration differences between regions. Asymmetrical arrangements may be required.

- Look forward, not backward: A review of provincial-municipal responsibilities should look ahead to future challenges, such as how Ontario’s aging population might affect local service costs.

- Start with health and social services: Instead of a comprehensive approach, a review should begin with a focus on public health, ambulance services, long-term care, social housing, social assistance, and child care. Cost-sharing is prevalent for these services, and therefore lines of accountability are most opaque and questions about local input and autonomy most pronounced.

Introduction

From the moment they wake up to the moment they go to bed, Ontarians interact with municipal services. The water they use to shower, the garbage they roll out to the curb, the roads they drive on to work, the transit on which they ride, and the streetlights that light up their street – all are services delivered to residents by municipal governments.

And yet, as is often the case, the story is more complicated than it appears.

In addition to the local services described above, municipalities deliver social housing and social assistance to those in need. They are responsible for long-term care homes, ambulance services, and public health programs. They are in charge of fire and policing. They run libraries, community centres, child care services, and more.

Furthermore, municipalities do little of this alone. The provincial government is involved in every aspect of local service delivery, through cost-sharing, policy setting, regulation, or other forms of entanglement. No fewer than 280 provincial statutes, and countless provincial regulations, policy frameworks, and service standards affect how municipalities in Ontario deliver services.[1]

This policy brief explores the complex relationship between the Province and Ontario’s 444 municipalities – how it has become so intertwined and why the time has come for a reassessment that ensures Ontarians receive the most effective, efficient, and highest level of services from their governments.

We’ve been here before. The Ontario government carried out the Local Services Realignment in the late 1990s and the Provincial-Municipal Fiscal and Service Delivery Review (PMFSDR) in the mid-2000s, both of which examined the division of roles, responsibilities, and funding arrangements between the Province and municipalities. Why go down this road again?

First, both the provincial government and municipal governments are facing mounting fiscal and service pressures due to an aging population, urban/rural population changes, a more competitive global economic environment, climate change among other challenges. It is always prudent to periodically ensure that the distribution of responsibilities between the Province and municipalities is as appropriate and effective as possible.

Second, the Province has expressed interest in modernizing and streamlining services.[2] This requires examining how responsibilities are currently shared between the Province and municipalities, and whether changes could improve service and ensure greater accountability for tax dollars.

Finally, unilateral changes to provincial funding for services usually force other governments to fill in the gaps. When that happens, service quality may deteriorate due to a lack of resources. It is imperative that the Province and municipalities work together to ensure services are effectively funded and delivered.

Previous work by Ontario 360 called for an independent review of provincial-municipal responsibilities in Ontario.[3] This paper lays the groundwork for such a principles-based review. It draws on published research, an analysis of municipal financial data, and insights from a roundtable of experts convened by the Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance (IMFG) that included academics and former municipal and provincial officials.[4]

Section 1 examines the current state of cost-sharing between the Province and municipalities across 15 service areas, and explains how the current situation came about. Section 2 sets out goals that should guide a review of provincial-municipal responsibilities, and compares the advantages and disadvantages of centralizing responsibilities to the Province or decentralizing to municipalities. Section 3 contains six recommendations for how to undertake a review of provincial-municipal service delivery and funding.

1. The State of Provincial-Municipal Responsibilities

Most Ontarians would be surprised to learn that local governments across the province collectively spend more than $64 billion every year on public services.[5] This money pays for everything from traditional “hard” services, such as roads and sewers, to so-called “soft” services, such as community programs and child care subsidies.

Spending on Local Services

To understand how local services are funded, including what expenditures are shared by local, provincial, and federal governments, we analyzed the most up-to-date municipal financial data collected by the Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, known as the Financial Information Return (FIR) database.[6]

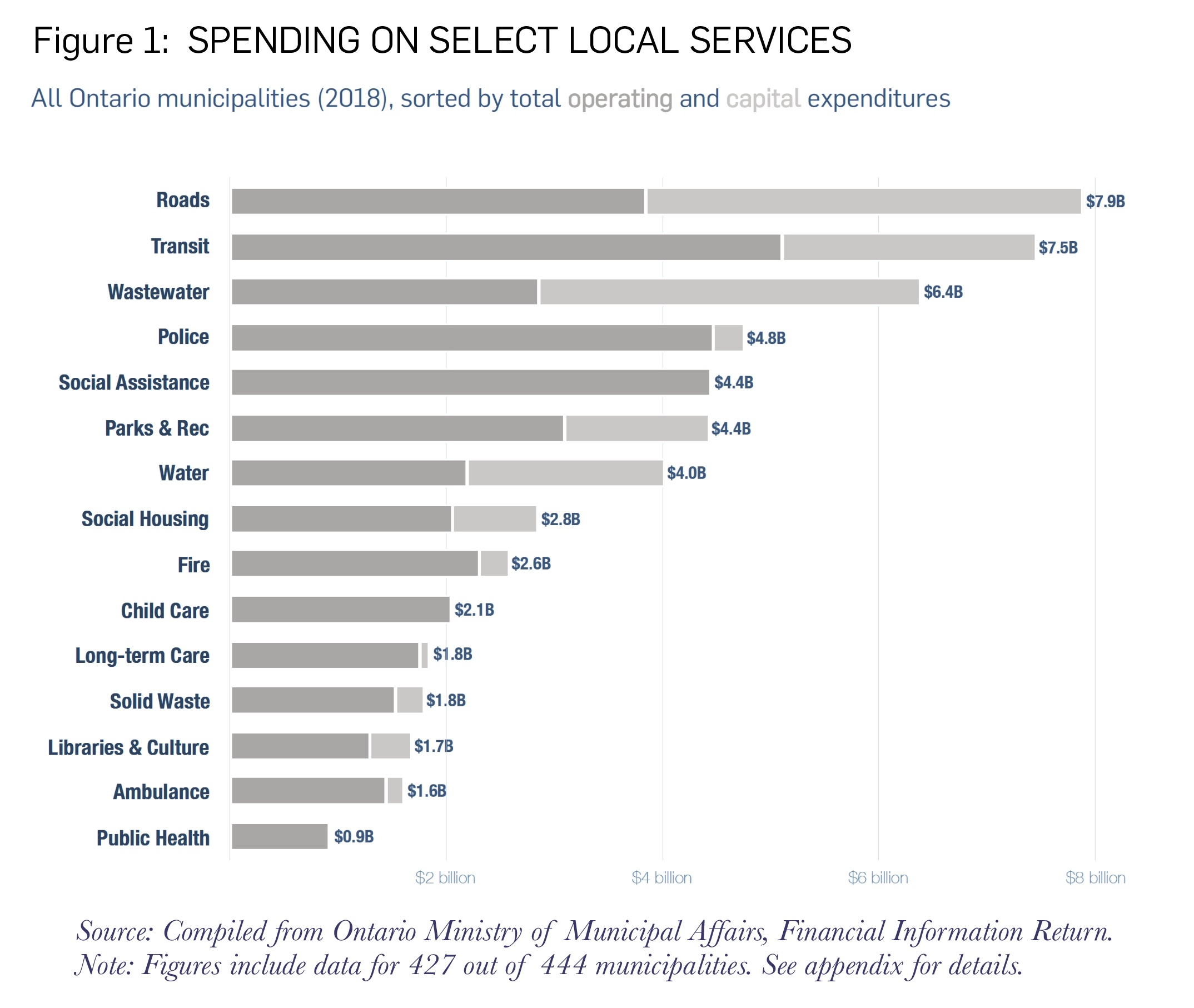

We analyzed municipal expenditures for 15 key services: fire; police; roads; transit; wastewater; water; solid waste; public health; ambulance; social assistance; long-term care; child care; social housing; parks and recreation; and libraries and culture (see the Appendix for details on the method).[7] Together, these services account for 85 percent of all local spending, or $55 billion (see Figure 1). Source: Compiled from Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs, Financial Information Return.

Source: Compiled from Ontario Ministry of Municipal Affairs, Financial Information Return.

Note: Figures include data for 427 out of 444 municipalities. See appendix for details.

Nearly $26 billion, or roughly 40 percent of all municipal spending in Ontario (combined operating and capital) goes to capital-heavy services: roads, transit, water, and wastewater treatment. About $11 billion, or nearly one-fifth of all local spending, goes to social services, such as social assistance, long-term care, child care, and social housing. Another $9 billion, or close to 15 percent of total spending, goes to emergency services, such as fire, police, and ambulance.

Totals and per-capita spending vary from one municipality to the other. Toronto, for example, spends more on public transit ($4.2 billion, or $1,434 per capita) than all 443 other Ontario municipalities combined ($3.2 billion, $305 per capita). Conversely, Ontario municipalities other than Toronto spend nearly three times more on roads ($675 per capita) than Toronto ($262 per capita).

Who Pays for Local Services?

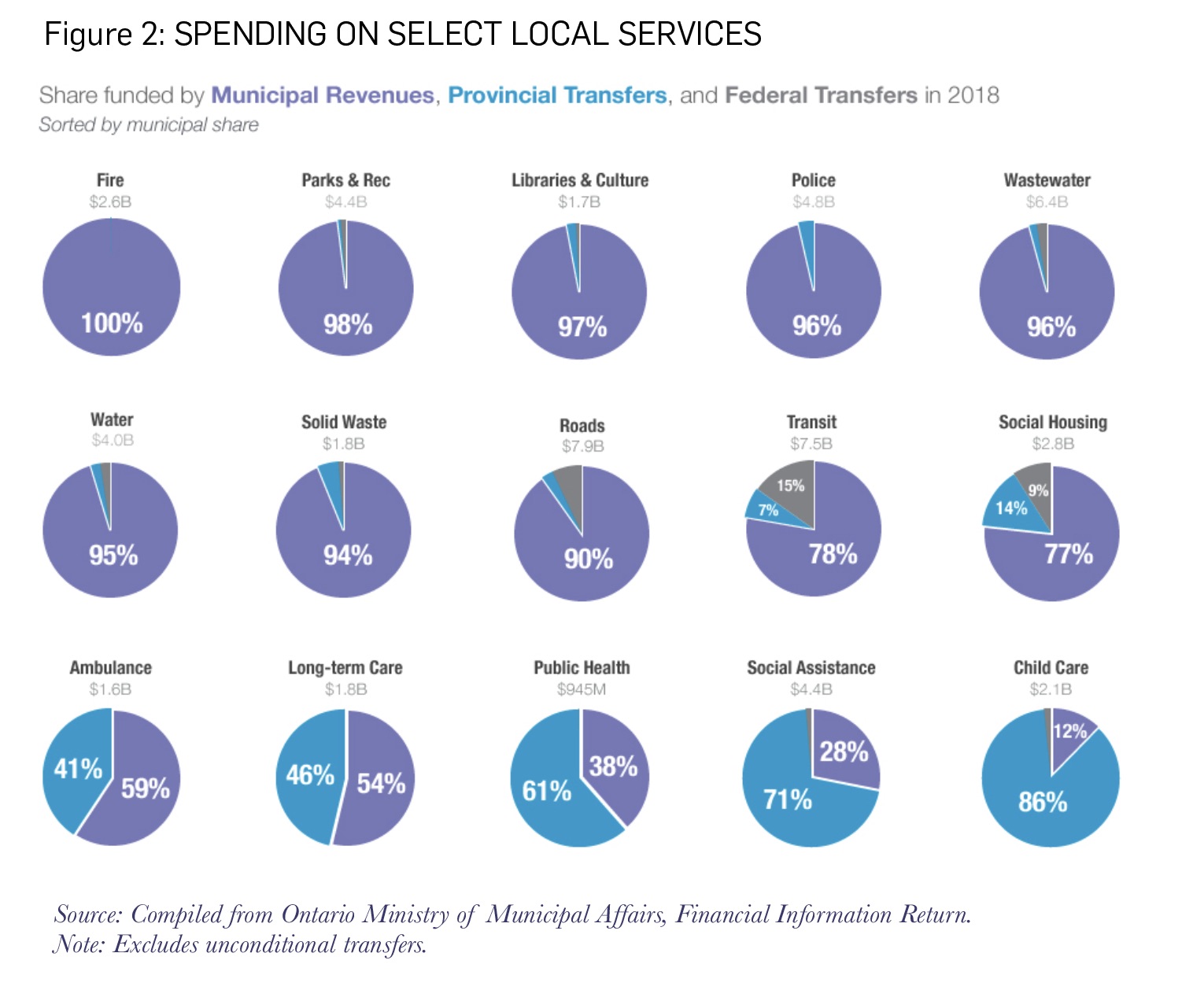

Just as important as how much municipalities spend on local services is who pays for these services. Not every dollar spent by municipalities is raised by municipalities themselves. The Province provides $9.4 billion in funding for local services, almost exclusively through conditional transfers.[8] Figure 2 presents the respective share of services funded by municipalities, through property taxes, user fees, and other own-source revenues, versus provincial or federal transfers. Overall, nearly 80 percent of local services selected for analysis are paid for through municipal own-source revenues, compared to 17 percent from provincial transfers, and 4 percent from federal transfers.[9]

Sorting local expenditures by municipal, provincial, and federal contributions exposes two important findings.

First, the share of funding by each order of government, especially between municipal and provincial governments, varies widely by service. Municipal contributions range from a low of 12 percent for child care services, to a high of 99.8 percent for fire services; conversely, provincial shares range from zero to 86 percent.

Second, these dramatic differences in funding shares by service area highlight the danger of making sweeping generalizations about how responsibilities are divided between the Province and municipalities. The fiscal equation changes from issue to issue, municipality to municipality.

The lack of uniform cost-sharing arrangements raises questions about the extent of provincial-municipal “entanglement” – the degree to which service delivery is complicated by shared financial responsibilities. To isolate these dynamics, we further divided financial data into two categories: services that are largely municipal, in which the provincial government contributes less than 10 percent of total service funding; and services that are highly intertwined, in which the provincial government contributes anywhere between 10 and 90 percent of overall funding.

Largely municipal services: includes “traditional” municipal responsibilities, such as fire, police, wastewater treatment, water, solid waste collection and disposal, parks and recreation, local libraries and cultural facilities, roads, and public transit.

Intertwined services: includes health and social services, such as child care, social assistance, public health, long-term care, ambulance, and social housing.

The most striking feature of the “intertwined” services is that each associated cost-sharing ratio follows, at best, an ill-defined rationale, or at worst, appears completely arbitrary. Most public services in this category are funded through complex cost-sharing arrangements that rarely follow any clear, principled criteria, whether based on population, fiscal capacity, or need.[10]

Funding arrangements are more often the product of political negotiations between provincial and municipal officials, or discretionary decisions taken by specific municipalities to address particular service priorities, or the unintended consequence of past attempts to rationalize provincial-municipal responsibilities.

The current funding mix for social assistance, for example, was negotiated between the Province, the City of Toronto, and the Association of Municipalities of Ontario in 2008, when the Province agreed to pay for 100 percent of Ontario Works and Ontario Disability Support Program benefits, and 50 percent of the programs’ administrative costs, which are implemented by municipalities.[11] The precise 50:50 split for administration costs is nothing more than a rudimentary compromise – the two sides simply met halfway.

Funding for social housing is a mixed bag of municipal (77 percent), provincial (14 percent), and federal (9 percent) dollars. Unlike social assistance funding, this is not the result of formal negotiations, but rather unilateral decisions by different provincial governments to invest or disinvest.

In the early 2000s, provincial spending on social housing was effectively zero.[12] Recent housing plans and infrastructure investment strategies have brought the provincial share, on average, back up to 15 percent of total funding – but only in the aggregate. As we will see, different municipalities across the province pay for different shares of social housing costs, without any direct tie to social or financial need, and with important impacts on some municipalities’ fiscal situation.

Even for services in which costs are shared based on clear criteria – such as child care, where provincial funding is allocated according to a strict, evidence-based Child Care Funding Formula – the underlying rationale for intergovernmental cost-sharing is not always clear.[13] For example, observers would be right to ask why child care is not a wholly provincial funding responsibility, similar to full-day kindergarten.

How Did We Get Here?

Many of the most questionable elements of the current system can be traced to policy decisions made in the 1990s.

In 1996, the provincial government created the Who Does What Panel. Chaired by David Crombie, the panel comprised 16 current and former municipal politicians and public servants with experience in both provincial and local government, as well as several independent scholars.[14]

The original mandate of the Who Does What Panel was to “disentangle” public service delivery across the province by reducing duplication and inefficiencies, and, where appropriate, enabling municipalities to manage their own affairs.

Rather than compile its recommendations into a comprehensive report, the group presented its findings in a series of 19 letters addressed to the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing. Altogether, the panel proposed more than 200 reforms to the education system and the delivery of social services, transportation and utilities, emergency services, assessment and property taxes, and general municipal administration.

A central principle guiding the panel’s work was that, “where possible, only one level of government should be responsible for spending decisions.”[15] Municipal governments, for example, should be solely responsible for “hard” services, such as services to property (e.g., police, fire), roads, transit, and utilities; and the provincial government should be solely responsible for “soft” services and redistributive programs, such as public health and social assistance programs.[16]

Only some of these recommendations were implemented. Even before the panel had completed its work, the Province initiated a process known as Local Services Realignment, which “uploaded” the full cost of public education to the Province, and “downloaded” services such as transit, roads, and property assessment to municipalities. The panel had suggested these changes, but the realignment did not stop there.

Most of the health and social services that the panel had recommended be solely funded by the Province, such as ambulances, public health, and child care, were instead either fully downloaded to municipalities, or realigned so that a larger share of costs were shifted to municipalities, which were ill-equipped to take on the extra financial burden.

In 2003, the Association of Municipalities of Ontario (AMO) and the City of Toronto began negotiations with the new Liberal provincial government to rectify the fiscal imbalance. In 2004, the Province announced it would restore its share of public health funding from 50 percent to 75 percent by 2007.[17] The next year, it created the Ontario Municipal Partnership Fund (OMPF), a targeted, unconditional transfer and equalization program for northern and rural municipalities, which today totals about $500 million.[18] And in 2006, it contributed an additional $300 million over three years for ambulance services.[19]

The culmination of these efforts was the Provincial Municipal Fiscal and Service Delivery Review, a formal upload agreement signed by the Province, AMO, and the City of Toronto in 2008, which committed the Province to assume the full cost of the Ontario Drug Benefit, the Ontario Disability Support Program, and Ontario Works benefits by 2018.[20]

Together, these reforms eliminated billions of dollars of financial obligations from municipal balance sheets. But they also added a new layer of conditions and constraints that has made the relationship between the Province and municipalities even more opaque.

Since coming into office in 2018, the Progressive Conservative government has focused on cost-sharing arrangements in three main areas: public health, ambulance services, and child care.

The 2019 provincial budget included plans to restructure public health funding over the following three years. Currently, costs are roughly split 60:40 (provincial-municipal) for Toronto and 70:30 for all other public health units. By 2022, the Province intends to revise these ratios to 50:50 for Toronto, 60:40 for six regions with a population over 1 million, and 70:30 for three regions with a population under 1 million.[21]

Ambulance services are expected to be restructured by consolidating 52 ambulance units to just 10 regional entities, and freezing funding contributions at 2017 levels – well below the 50:50 split envisioned in 2006.[22]

Finally, the Province has proposed a formal 80:20 provincial-municipal cost-sharing arrangement for its child care expansion plan, which is still in development. At the time of writing, the Province had not clarified whether existing subsidies will be affected.[23]

2. Setting up the Goals of a Review

Nearly 25 years after the Who Does What Panel stressed the importance of clarifying lines of accountability, current cost-sharing arrangements between the Province and municipalities remain a “tangled web” of overlapping obligations.[24]

Is there a better way to assign functions between governments? What goals should underlie a review of provincial-municipal responsibilities?

The answer to these questions rests partly on determining the costs and benefits of planning, funding, and delivering services at the provincial versus municipal level – that is, whether to centralize or decentralize responsibilities.

Centralization vs. Decentralization

Some experts argue that as a general rule, services should be assigned to the lowest level of government where efficiency and equity can be achieved.[25] This is known as the principle of subsidiarity. As Bahl and Bird have written, “people are more likely to get the package of public services they want, if not necessarily what others think they should want, under a decentralized system than under a centralized system.”[26]

Some studies have found that decentralization to local governments fosters the involvement of local organizations in policy-making, including businesses, residents’ groups, arts organizations, and environmental groups. These organizations, the argument goes, are more likely to have access to local governments than to higher levels of government. Removing local governments from policy-making and decision-making can thus reduce the voice of these organizations.[27]

Local governments are also sites for innovation. Emerging policy solutions can be more easily tested at a small scale before adoption by others. A successful training model for long-term care workers in Peel Region, for example, has been adapted and adopted by the City of Toronto.[28] Decentralization can feed this innovative capacity by creating more room for experimentation.

Despite these arguments, centralizing functions (to the provincial level) is warranted and desirable in many situations.

Centralization is often required to ensure common service standards, such as in health care and education. Centralization can also result in economies of scale (where the cost per unit of output falls with increasing scale), and help ensure fairness. Some services, such as social services, are redistributive in nature, meaning that they benefit low-income households relatively more than high-income households. The most effective and equitable way to fund redistributive services is through a progressive tax, such as an income tax, which is currently levied only at the provincial and federal levels.[29]

Finally, centralization can address spillover effects. A highway, for instance, can cross municipal boundaries. Centralizing responsibility, or at least leaving some oversight at a higher level of government, ensures the optimal level of service for the region; decentralization, meanwhile, can lead to municipalities making service decisions based on the needs of local residents only.[30]

There Is No Golden Rule

The arguments for centralization versus decentralization – for increased provincial versus municipal funding and responsibility – do not provide a definitive answer on which is best.

Deciding who does what is a matter of balancing the need for uniform standards and the desire for local input and innovation. It is also a matter of balancing competing priorities and adapting to the particular context of a region, or the demands of delivering a particular service.

Past studies have highlighted the importance of distinguishing between the needs of large cities, rural municipalities, and northern communities; emphasizing accountability; and focusing on improving service quality rather than ensuring a revenue-neutral outcome when realigning responsibilities.[31]

These considerations and past recommendations point to a set of goals for any review of provincial-municipal responsibilities:

- enhancing quality of service;

- ensuring effective and efficient service delivery;

- safeguarding accountability;

- sharing costs fairly.

It is important to avoid a one-size-fits-all approach. In some cases, it may be beneficial to disentangle provincial and municipal involvement by assigning responsibility to one government or the other. Some services, though, may benefit from greater coordination and cooperation between levels of government.[32]

3. Recommendations for a Review of Provincial-Municipal Responsibilities

We offer six recommendations as a guiding framework for a productive review of provincial and municipal responsibilities in Ontario:

1. Take a Collaborative Approach

Municipalities are often referred to as “creatures of the provinces.” Unfortunately, too many changes to provincial-municipal responsibilities have been undertaken within the top-down spirit of that phrase.

That’s not to suggest that the Province has no role in municipal affairs. Provincial action has led to important achievements such as the creation of regional governments and the Greenbelt.[33] A top-down approach to a review of provincial-municipal responsibilities, however, will not produce the best results for Ontarians.

Municipalities should be equal partners in any review and co-creators of the ultimate policy decisions. A collaborative approach, while more time-consuming and more complex, allows for the consideration of local concerns and best practices and ensures greater buy-in when a final agreement is reached.[34]

Special care should also be taken to ensure Indigenous communities have an appropriate role in the review. Governments have a duty to consult and accommodate Indigenous communities on matters that impact Indigenous and treaty rights.[35] The Province would need to determine if and to what extent this duty to consult is triggered by a review of provincial-municipal responsibilities.

In any case, since 85 percent of Indigenous people in Ontario live in urban areas, ensuring access to culturally appropriate services for Indigenous people in urban areas should be a consideration in any discussions of how services are planned, funded, and delivered.[36] Any realignment of responsibilities could impact existing governance arrangements between municipalities and Indigenous communities.

A robust collaborative approach should also include non-governmental actors, such as business groups and service providers. These groups are instrumental in shaping cities, and in many cases deliver local services, and thus are central to the governance of municipalities. Moreover, they have invaluable insight into what works and doesn’t work in the delivery of services in Ontario.

Collaboration need not be achieved all at once. One possibility raised at the expert roundtable is for the Province to run pilot projects to test the effects of giving greater responsibility to municipalities. The Province could determine goals for service delivery in certain areas, provide a fixed budget, and let municipalities identify the best way to meet those goals. The results could be scaled up, whether through sharing best practices or by expanding the approach to other service areas.[37]

2. Follow the Pay-for-say Principle and Avoid Unfunded Mandates

Discussions about cost sharing cannot be separated from discussions about decision-making authority. The pay-for-say principle is one way to ensure decision-making power and funding responsibility are appropriately linked.

The pay-for-say principle means that if a government has input into how a service functions, it should also have a corresponding responsibility to pay for the service. Decision-makers, in short, need to have “skin in the game” for the services they control.

This principle suggests a useful initial criterion for allocating responsibilities between the Province and municipalities (see Figure 3): The more a service needs to be standardized and regulated at the provincial level, the more it should be funded at that level; the more local input and variation is desired, the more it should be funded by municipalities.

For services that fall somewhere in the middle, cost-sharing arrangements may be desirable. In these cases, agreements with clear and distinct responsibilities, as well as procedures for resolving conflicts, are essential.[38]

Deciding where a service falls along the spectrum in Figure 3 is only the beginning of the conversation. The pay-for-say principle refers only to a link between decision-making and funding. It does not determine whether or how governments should split responsibility for strategic and planning decisions about service standards, on the one hand, and delivery of the service, on the other.

Such a split can be beneficial. It is often the case that local residents demand services beyond the provincial standard, and it is appropriate that it fall to municipalities to pay for these enhancements.[39] Some at the expert roundtable suggested that, in such cases, the base level of service mandated by the Province could be funded provincially, leaving municipalities the option to offer additional services at their own cost.

Following the pay-for-say principle can also help avoid unfunded mandates – situations in which provincial policy decisions result in disproportionate costs for certain municipalities without commensurate funding to help meet those costs. For example, fire protection is strictly regulated at the provincial level, meaning that the Province can unilaterally increase service standards without helping pay for the additional cost of those changes.

To guard against unfunded mandates, it may be appropriate to establish a principle along the lines of Denmark’s Extended Total Balance Principle. According to this principle, if a decision by a higher order of government leads to increased costs at the local level, the local municipality receives compensation from the higher order of government. Similarly, any savings incurred at a local level due to a decision by a higher order of government are returned to the higher order of government.[40]

A review should also analyze less obvious forms of downloading in which policy decisions at the provincial level create unexpected costs for local governments, and vice versa. Ambulance services, for example, are greatly affected by the wider health care system, which is provincially controlled. Ambulances cannot discharge a patient at a hospital until there is a bed available, which can take hours because of long wait times at some hospitals.[41] Municipalities bear the cost of these delays, even though the wait times are out of their control.

Other examples of cross-subsidization between the healthcare system and the municipal sector include the Province requiring every upper or single-tier municipality to maintain at least one long-term care home, and expecting municipal governments to incur significant and larger long-term debt commitments for the refurbishment, expansion, and equipping of local hospitals.[42]

A realignment of responsibilities could resolve these issues. It is worth considering, for example, whether ambulance services or long-term care should be fully integrated with the broader health care system at the provincial level.[43]

3. Consider Local Revenue Capacity

Any shift of responsibility – whether it is down to municipalities or up to the Province – needs to take into account whether the government that will take on the responsibility has the necessary and appropriate revenues to meet that responsibility.

Downloading raises the question – can a municipality raise sufficient revenues to deliver the service effectively? For fiscally weak municipalities, are there steps they can take to improve their fiscal capacity, such as sharing their tax at a “regional” level?

It is also important to consider whether municipal funding sources are appropriate for the services municipalities are asked to fund.[44] Although the property tax is a good tax for funding local services such as local roads, parks, and recreation centres,[45] it is not as effective at funding redistributive services, because it is less directly linked to the incomes of those being taxed.[46]

For example, municipalities in Ontario currently pay three-quarters of social housing costs. These costs put great pressure on the property tax, which is not as progressive as an income tax, and therefore not the best way to pay for social housing. A review of provincial-municipal responsibilities should examine whether some services should no longer be funded by property tax revenues.

The review should also consider funding inequities between different municipalities with respect to social housing. The City of Toronto spends $933 million, or $315 per person, on social housing. Of this total, the provincial government contributes just $333,250, or $0.11 per person – a share of just 0.04 percent. Compare this to municipalities in the rest of the province, which together spend $1.9 billion on social housing, an average of $182 per person. In these municipalities, the Province contributes a total $405 million, or an average of $38 per person – a 21 percent share of all operating and capital costs.

There are two justifications for provincial funding of social housing: first, the Province has more appropriate revenues to undertake redistribution, and second, provincial funding reduces pressure on municipal property taxes, especially in cities that bear a disproportionate burden of the cost.

4. Respect Local and Regional Differences

Different municipalities in different regions have different service needs and incur different costs. Any review of provincial-municipal responsibilities should analyze costs on a per-capita basis and take into consideration local and regional differences when determining fair cost-sharing arrangements.

For example, fast-growing suburban municipalities, such as Milton, spend 19 percent more than the provincial average building new roads ($693 vs. $584 per capita). Large cities, such as Ottawa, spend twice as much on public transit ($664 per capita) than all other municipalities excluding Toronto ($305 per capita). And northern municipalities, such as Timmins, spend 60 percent more on ambulance services ($146 per capita) than municipalities in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area ($91 per capita).

Furthermore, of Ontario’s 444 municipalities, 267 have a population of less than 10,000 and 192 have a population of less than 5,000.[47] The smallest municipalities have relatively few employees and often a very small non-residential tax base, making them largely dependent on the Province for fiscal sustainability.

These differences may necessitate the creation or further development of asymmetrical cost-sharing arrangements that take into account the needs, costs, and fiscal capacity of specific municipalities in different regions. At the very least, in the context of a discussion of regional and local differences, a review of the Ontario Municipal Partnership Fund (OMPF), a transfer program which targets the province’s 389 northern and rural municipalities, is warranted.[48]

Finally, a review of provincial-municipal responsibilities should consider how other governance institutions – existing or new – could help deliver services in Ontario.[49] For example, the Northern Policy Institute has published a report recommending the implementation of regional governments throughout Northern Ontario.[50] In the GTHA, in the case of services such as transit, standard-setting could be left to regional bodies, with local entities taking charge of delivery.[51]

In general, any review should consider the question of whether regional governments, counties, conservation authorities, Indigenous communities, the private sector, and other bodies could play new roles in service planning or delivery.

5. Look Forward, Not Backward

Reviews of provincial-municipal responsibilities are, by their nature, backward-looking. They analyze past costs for services and are based on past demand. This approach can help correct for inefficiencies and inequities that reveal themselves over time. However, a review of provincial-municipal responsibilities should also be forward-looking. What may seem like an appropriate way to divide responsibilities today may change drastically in a few years.

Consider long-term care services for seniors. A recent survey by Strategy Corp. found that municipal CAOs expressed concern that costs for long-term care are mounting while funding is decreasing.[52] Moreover, the fiscal pressures differ by location; seniors make up a larger proportion of the population in rural communities versus urban areas.[53]

Demographic trends in the GTHA differ from those in the rest of the province. Thanks to strong international migration, the GTHA has a relatively young population compared to Ontario’s rural and northern communities – a gap that will widen over the coming decades.

Today, seniors make up roughly 13 percent of the population of Peel Region, compared to 27 percent in the City of Kawartha Lakes. As a result, Peel spends just $68 per capita ($101 million) on long-term care, one-third less than Kawartha Lakes, which spends $190 per capita ($14 million). This financial burden will grow over time, as the projected share of seniors in Kawartha Lakes – similar to many other rural communities – increases to 37 percent by 2046.[54]

A review of provincial-municipal responsibilities should look ahead to these coming challenges, as well as those posed by artificial intelligence, changing municipal workforces and delivery models, and new economic and commercial realities that affect local tax bases.

6. Start with Health and Social Services

Rather than conduct a full-scale review of all cost-sharing arrangements, a review of provincial-municipal responsibilities should focus on health and social services, particularly public health, ambulance services, long-term care, social housing, social assistance, and child care.

Health and social services raise the most questions, including whether the pay-for-say principle is being respected, whether municipalities face unfunded mandates, and whether municipal revenue sources are sufficient and appropriate for funding these services.

Other services, such as fire and transportation, could benefit from a review to resolve issues of unfunded mandates and the high cost of roads and transit for rural areas and big cities.[55] However, there is more to be gained from focusing on a smaller set of service areas first, with lessons from the process taken into account for other reviews down the road. It would be better to take an iterative approach and not fix what is not broken.

Conclusion

When it comes to service delivery in Ontario, the Province and municipalities are highly interdependent. Whether through regulations, planning, funding, or other arrangements, there is hardly any service area where the two levels of government are not connected.

To ensure the highest quality service for Ontarians, it is necessary to look at how responsibilities are split between the Province and municipalities, and to review whether new arrangements could produce more effective and efficient outcomes. The Province is undertaking some of these reviews already. This report offers a principles-based approach to avoid some of the ill-defined and arbitrary divisions that characterize key service areas today.

This paper has put forward six recommendations for undertaking precisely such a principles-based review in order to achieve a more effective and rational system for delivering the services Ontarians rely upon every day.

Appendix – Methodology

At the time of writing, 17 municipalities had not yet submitted their 2018 Financial Information Returns to the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. Therefore, any figures throughout this report that are based on FIR data correspond to spending totals for only 427 out of 444 Ontario municipalities. For example, references to long-term care spending totals in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton area exclude data for Richmond Hill, which has not yet submitted its 2018 datasheets.

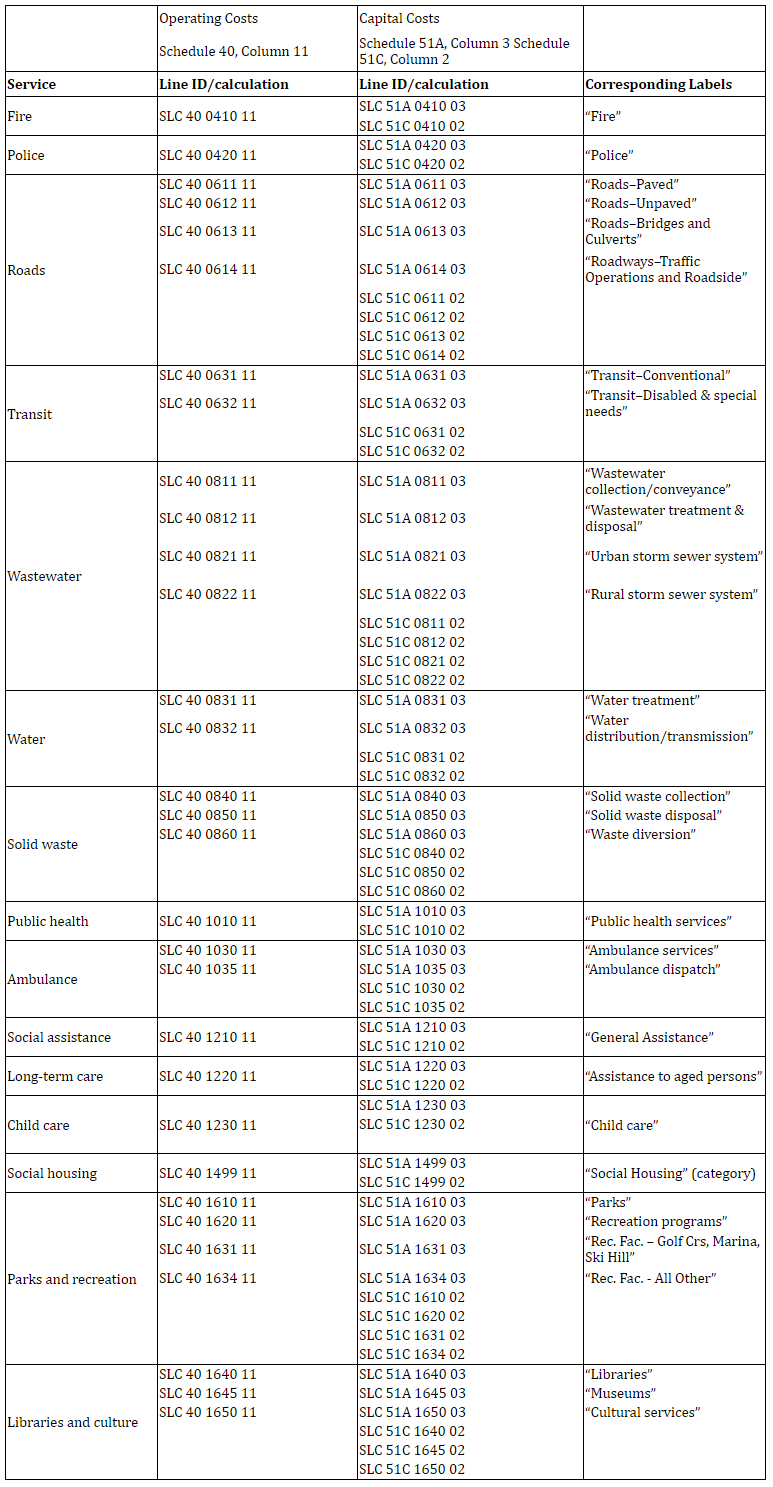

Source data for 15 selected service areas:

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants of the roundtable for their valuable insights. The views represented in the paper are the author’s alone. Thank you to Philippa Campsie for her helpful edits, and to past and present Urban Policy Lab graduate fellows Matthew Plouffe and Aidan Carroll for their research assistance.

Gabriel Eidelman is the Director of the Urban Policy Lab at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, where he teaches classes on urban governance and public policy. His scholarly research focuses on cities and urban governance in North America, and has been published in the journals Cities, Urban Affairs Review, and the Journal of Urban Affairs. In 2018, he co-authored an Ontario 360 transition brief on municipal affairs, and previously, co-led the University of Toronto’s City Hall Task Force.

Tomas Hachard is the Manager of Programs and Research at the Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. Prior to joining the Institute, he was a Senior Policy Analyst at the Council of Ontario Universities, where he led major projects in policy, communications, and government relations. Tomas was previously a journalist and wrote for publications including The Atlantic, The Globe and Mail, NPR, The National Post, and The Guardian.

Enid Slack is the Director of the Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. She has written extensively on property taxes, intergovernmental transfers, development charges, financing municipal infrastructure, municipal governance, and municipal boundary restructuring. Recent publications include Financing Infrastructure: Who Should Pay? and Is Your City Healthy? Measuring Urban Fiscal Health (both co-edited with Richard Bird). In 2012, she was awarded the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal for her work on cities.