Policy Papers

A Lifelong Learning Strategy for Ontario

André Côté, Alexi White and Michael Cuenco explore the need for Ontario's Higher Education system to move beyond traditional programs and models.

Issue Statement

The pandemic’s impacts on Ontario’s workforce were immediate, profound and prolonged. As of October 2020, employment in Ontario remained 3.8 percentage points below pre-pandemic levels, with nearly 300,000 fewer Ontarians in work.[1] The acceleration of advances in technology and automation risk further amplifying job displacement, skills obsolescence and vulnerability for workers with lower levels of education and skills.[2]

Looking to enhance skills or transition careers, these learners are increasingly turning to lifelong learning opportunities. A massive emerging cohort of working-age adults who will need to learn, upskill and retrain throughout their careers will reinforce trends that were already driving a new lifelong learning paradigm.[3] This presents an opportunity for Ontario’s higher education institutions at a time when they are coping with declining public investment, skepticism over their relevance in a changing labour market, and a pandemic that has shuttered campuses.

To seize this opportunity, provincial policymakers and higher education institutions must move beyond traditional program and delivery models and embrace shorter, flexible, stackable, competency-based, part-time, online, and industry-tied models.

This Ontario 360 policy paper outlines how Ontario policymakers and provincial higher education institutions can be more responsive to these new and emerging labour needs. In particular, it scans emerging institutional models and examples at home and abroad, and offers a set of principles and proposals for policymakers to reorient the province’s higher education system for lifelong learning. For the full white paper, see Higher Education for Lifelong Learners: A Roadmap for Ontario Post-Secondary Leaders and Policymakers.

Decision Context

Even before COVID-19, the world of work was changing rapidly, and with it the demands placed on higher education. In Canada and across Western countries, a shift away from stable, full-time employment toward freelance, part-time or “gig” work is creating a new class of precarious workers.[4] There is growing demand for higher levels of skills and education, as workers in low-skill sectors and, increasingly, medium-skill sectors see increased job displacement. More broadly, research finds that nearly half of Canada’s workforce has lower skills than required to fully participate in the labour market.[5]

One part of the solution lies with Ontario’s skills-training system. The provincial government is undertaking a transformation of Employment Ontario (EO) aimed at creating an integrated, outcomes-focused, and client-centred system. The system, which delivers a suite of employment and training services funded by the province and delivered primarily by a network of local service providers, is shifting to a performance-funding model, delivered through a network of private and non-governmental Service System Managers (SSM) across 15 regions. As another Ontario 360 paper highlights, EO should serve not just the long-term unemployed and those facing the greatest barriers to the labour market, but growing segments of workers affected by labour market disruptions and technological change.[6]

But employment services and training programs like Second Career are geared to only one segment of working-age clients along the skills spectrum. EO caters primarily to low-skill learners, who are more barriered within the labour market, requiring literacy and basic skills training, employment services and social programs. Higher education is generally not equipped to support these individuals, though some do access employment services, vocational education or apprenticeship training through Ontario colleges, and could progress to other learning opportunities as they advance in their career pathways.

At the other end of the skills spectrum are highly skilled learners seeking elite, high-cost professional programs like executive MBAs or leadership development training. There is already a well-established market for these learners, often paid by employers, with a competitive market among higher education providers.

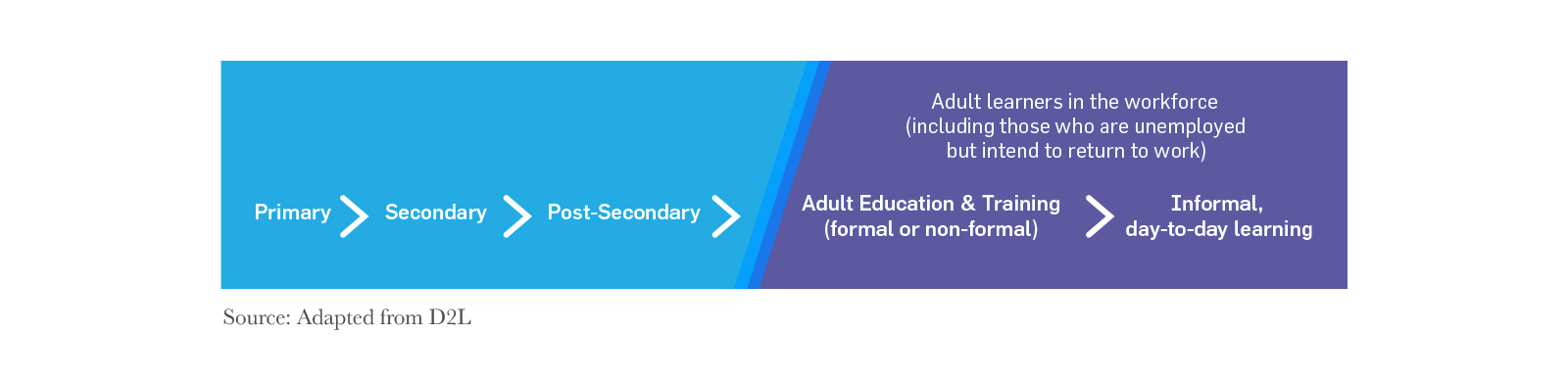

Figure 1: The Lifelong Learning Continuum

Between these poles is a diversity of middle-skilled workers across industries and occupations, each with unique challenges and goals. For these prospective lifelong learners, some need a short course to keep skills current or to secure a promotion; others are looking to make a career change and require more intensive education towards a new credential — preferably one that provides credit for what they already know.[7]

The typical motivations of these lifelong learners include:

- Career benefit, as well as earnings-related factors (to keep a job or advance to a new one; to secure increases in pay and benefits).

- Seeking non-degree credentials and skills-based education and training, through flexible, online and asynchronous models to fit into a busy life.

- Low-cost options, particularly where they do not have access to training and development programming or financial support through their employer.

- Common challenges with participation and completion, including time commitment, logistical factors like time away from work or course schedules, and self-doubt about their ability to return to school.[8]

Meanwhile, as demand grows among these lifelong learners, higher education institutions in Ontario now face a set of growing stresses at the systemic and institutional levels:

- Traditional teaching and learning models have not adapted adequately to changing student demands and labour market needs. Higher education — particularly the university sector — has been confronted with a growing list of critiques to the still-dominant, campus-focused program models: long and relatively inflexible programs; inadequate recognition of prior learning; slow or limited innovation in pedagogy; insufficient student supports for career-readiness; weak alignment to labour market needs; and a limited commitment to online and digital-enabled learning.[9],[10]

- Some public institutions face threats to their financial sustainability, which COVID could be amplifying. Over the past decade, per-student funding of Ontario’s post-secondary institutions has fallen by one percent in real terms and remains the lowest in the country.[11] Demographics are shrinking the population of college-aged students in Ontario, putting pressure on domestic enrolments just as institutions’ expenses continue to grow.[12]

- The provincial post-secondary policy agenda continues the shift towards differentiated mandates, performance-based funding, and alignment with economic and workforce priorities. Through the third round of Strategic Mandate Agreements (SMAs) negotiated with its 45 colleges and universities, the government of Ontario signalled an escalation in performance-tied funding to 60 percent of operating grant funding.[13]

Taken together, the ongoing challenges to higher education, the emerging policy agenda at Queen’s Park, and the effects of the pandemic, create many of the preconditions for a shift toward lifelong learning models.

The Emerging Marketplace for Lifelong Learning

Among working-age learners and employers, there is further evidence of demand for new forms of short-duration micro-credential programs.[14] A 2020 survey conducted for Higher Education Strategy Associates estimated a potential market of over seven million Canadians (proportionately, about three million Ontarians) for new micro-credential programs, provided they are offered with sufficient flexibility, brevity and specificity in skills development.[15] While awareness of micro-credentials is still limited, 80 percent of employers and employees surveyed expressed interest in micro-credential programs once they fully understood the concept. In the more mature U.S. market, research by Strada Education found that 68 percent of adults considering enrolment in education prefer non-degree pathways, up from 50 percent a year ago.[16]

In response to this demand, the higher education and workforce development field is becoming much more crowded and competitive in pursuit of these working-age learners. An array of private players is angling to capture this market, ranging from private online universities (for instance, University of Phoenix) and fee-based MOOC providers (Coursera), to à la carte online course repositories (LinkedIn Learning), private career colleges (General Assembly and other coding schools) and education and workforce training companies (Maximus). Many of the new players are now active in the Ontario marketplace, either as competitors or as collaborators with public institutions.

For the most part, Ontario’s public post-secondary institutions have not yet embraced new models of program design and delivery that have been successful elsewhere. Working-age learners typically seek or require more short, modular and micro-credentialed programs; more employer and industry alignment; more online or blended, as well as competency-based models; and better services and social supports for online learners.

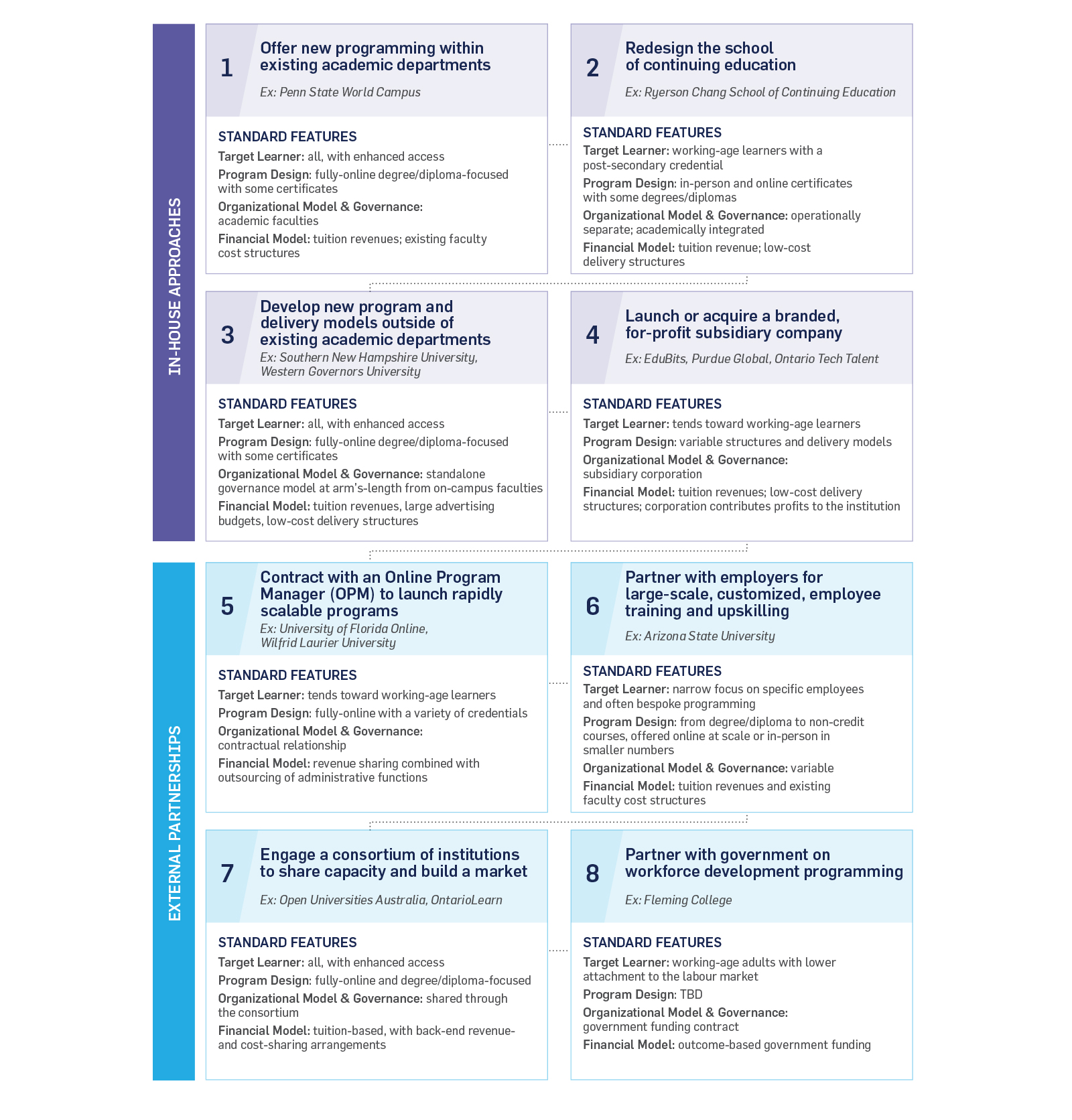

For those post-secondary institutions considering becoming more active in the world of lifelong learning, there are various models in Ontario and internationally from which to draw. We group our analysis into eight emerging models that are divided into two categories: in-house approaches developed under the full control of the institution, and external partnerships where the institution leverages its shared interests with the private sector, government or other institutions.

The models and examples are described in more detail below, with the summary table roughly capturing the standard features of each model. For more extensive descriptions of all the models, see the full white paper.

Figure 2: Summary Table – Emerging Models for Serving Lifelong Learners

In-House Approaches

1. Offer new programming within existing academic departments

Perhaps the most obvious pathway to expanded offerings for non-traditional students is to build new capacity in-house through existing academic departments. Penn State World Campus, for example, offers over 150 online degree and certificate programs taught by the same faculty who teach on campus, all integrated with Penn State’s academic and student-support infrastructure. Strong recruitment and marketing have been key to Penn State’s success, as has a long history and cultural acceptance of distance learning, which dates back as far as 1892.[17]

Other U.S. public universities have seen less success, or outright failure, using this approach. The University of Illinois Global Campus lasted only a year before it was wound down[18], and the University of Texas shuttered its Systems Institute for Transformational Learning after pouring $75 million into the initiative.[19] In both cases, observers blamed overambitious business plans and faculty resistance.

2. Redesign the school of continuing education

Separated from core academic operations, schools of continuing education typically offer a range of courses and certificates both online and in-person for academic or non-academic credit. Boasting 84 certificate programs, over 1,300 courses, and over 70,000 enrolments annually, Ryerson University’s G. Raymond Chang School of Continuing Education is perhaps the most successful example in Ontario, and is defined by its strong culture of integration with Ryerson’s academic departments.

Most continuing education certificates at the Chang School are Senate-approved for academic credit, and a series of shorter offerings can be stacked to form a higher-level academic credential. A “collaborative model” is used to spell out the partnership between the Chang School and Ryerson’s faculties, and academic coordinators are appointed by the faculties to ensure the quality of continuing education continues to meet the faculty’s own standards.[20] Four-in-five Chang School students already have a post-secondary credential, and this number is increasing, particularly in new industry-specific offerings.

3. Develop new program and delivery models outside of existing academic departments

Western Governors University (WGU) and the University of Southern New Hampshire (USNH) are two of North America’s largest providers of lifelong learning for working-age adults, and they credit their success to more flexible, innovative approaches that are often easier to realize outside of traditional academic structures.

WGU has embraced competency-based education and uses a unique model of instructor specialization that splits the design, teaching, and evaluation roles that are traditionally assigned to one instructor. Each student is assigned a program mentor to help with the creation and maintenance of a personalized learning plan amidst the increasingly “unbundled” nature of the learning experience.[21] Rapid admissions processes minimize the administrative burden on students, and tens of millions is spent on aggressive marketing focused on the 30 million Americans who have some college credit but who never graduated.[22]

4. Launch or acquire a branded, for-profit subsidiary company

As a variation on the previous model, some institutions opt to separate their lifelong learning operations by launching a new brand as a for-profit subsidiary. New Zealand’s Otago Polytechnic and, closer to home, Ontario Tech University, each recently launched for-profit subsidiaries that offer micro-credentials for direct enrolment, as well as customized corporate offerings.[23]

U.S.-based Purdue University took a different approach, acquiring for-profit Kaplan University and rebranding it as Purdue Global, while the University of Arizona recently announced it will acquire the online Ashford University, rebranding it as University of Arizona Global Campus. Consolidation of online learning providers is expected to continue and may lead to more of these deals in the future.

External Partnerships

5. Contract with an Online Program Manager (OPM) to launch rapidly scalable programs

Another model for rapidly expanding into online offerings is to contract with an online program manager (OPM) — a private, for-profit developer. Wilfrid Laurier University (WLU) took a measured approach when it contracted with Keypath Education in 2016 to offer the university’s first two programs entirely online.[24] Keypath provides student recruitment and support services, as well as strategic support and marketing. The programs were designed specifically for those who benefit from the increased flexibility; for example, the BA in policing was open only to current police officers.

OPMs are a natural option for institutions that are looking to quickly develop an online offering but lack the development capacity to get the courses up and running online, the funds to advertise it, or the administrative capacity to handle enrolment and other related transactions. OPM partnerships can have a dark side. The worst examples involve lengthy, unbreakable contracts for bundled services, paid for through a shared tuition revenue model that incentivizes aggressive recruiting.

6. Partner with employers for large-scale, customized, employee training and upskilling

Corporate interest in lifelong learning has led to a wave of exclusive partnerships between companies and higher education providers. For example, Arizona State University (ASU) and Starbucks have partnered on the Starbucks College Achievement Plan, which covers tuition fees for Starbucks employees.[25] As of spring 2019, there were about 12,000 Starbucks employees enrolled in ASU classes, accounting for 27 percent of all ASU online students that semester.[26] ASU has added a similar arrangement with Uber; eligible Walmart employees can now study toward an online degree from the University of Florida, Brandman University, or Bellevue University for $1 a day; and FedEx Express partnered with the University of Memphis Global to design custom degree programs that are free for employees.[27],[28],[29]

For the academic institution, these partnerships present a captive market with much less need for aggressive marketing and recruitment strategies. For the employer, offering education and training through reputable higher education providers is a retention tool and a long-term investment in the quality of employees.

7. Engage a consortium of institutions to share capacity and build a market

Given the right circumstances, higher education institutions sometimes choose to share capacity through the formation of a consortium. With competition for online learning inherently more global, there is a strong business case for local cooperation under a shared brand. For instance, Ontario Learn has enabled all 24 Ontario colleges to share over 800,000 course enrolments over the last 25 years. Open Universities Australia (OUA) similarly serves about 350,000 learners through courses and programs offered by 17 Australian universities, with no academic entry requirements for most undergraduate subjects (i.e. “open” enrolment).[30]

8. Partner with government on workforce development programming

Launched in 2019, the Ontario government’s ambitious redesign of the employment and training system is piloting a new administrative model in three regions of the province.[31] With the selection of Fleming College as the Service System Manager for Muskoka-Kawarthas region, the Employment Ontario transformation also offers a compelling test case for partnership between higher education institutions and public workforce programming.

Fleming already operates two employment services locations, and the college believes the SSM opportunity links with its focus on “providing learners with skills aligned with labour market needs to ensure broader and sustainable employment in our communities.”[32] Specific details about the Fleming SSM model are not yet available, but the pilot, which runs to 2022, could lead to new opportunities for symbiotic integration of the college system with employment services and workforce development programs across Ontario.

What are the key takeaways for Ontario policymakers from these eight different models for incorporating lifelong learning into post-secondary institutions?

- Institutions should identify the learners they can best serve along the skills continuum.

- Program design should respond to learner needs.

- In choosing a model, institutions should build on their strengths and capabilities.

- Private providers offer significant potential benefits but also risks.

- Partnerships with other institutions, employers and local partners hold promise and reduce risk.

Decision Considerations

Just as there are compelling reasons for institutions to expand their offerings for working-age lifelong learners, there is a strong case for the provincial government to use the policy and fiscal levers at its disposal to support and encourage institutions to innovate in this space. This section lays out a set of principles and proposals for Ontario policymakers to advance a lifelong learning agenda.

(For guidance directed toward higher education presidents and administrators, see the full white paper.)

Principles to guide a provincial lifelong learning agenda

The Government of Ontario is well-positioned to advance a lifelong learning agenda, as part of a broader strategy for higher education and the province’s workforce. Its Strategic Mandate Agreements (SMAs) and expanded performance-based funding model are important levers for establishing provincial objectives and financial incentives, formalized through institution-by-institution plans. These reforms, along with the Employment Ontario transformation cited above, can allow for greater alignment between higher education and workforce systems over the medium- and long-term. Targeted investments, such as recent funding commitments for micro-credentials and COVID recovery re-employment programs, offer short-term carrots to institutions, employers and employment service providers.

At the same time, Ontario continues to lack clearly defined goals for reform in the higher education system, much less an articulated strategy and policy agenda for stewarding change. The SMAs and funding reforms, while promising stewardship levers, have been criticized for lacking clear and ambitious objectives, for failing to adequately address data collection shortfalls, and for introducing faulty performance metrics, among other things.[33]

Other reforms, such as to student assistance and tuition frameworks, similarly lack coherence without anchoring within a broader strategy. A vision for lifelong learning should be part of this strategy, either as a standalone objective or as part of more detailed goals and metrics in areas already identified as government priorities, including labour market alignment and community impact.

Moving from vision to policy, the following set of broad principles would inform a clear government agenda for expansion of lifelong learning:

- Quality, value and outcomes for learners; through recognition of prior learning, high standards for programs and pedagogy, a focus on completions and career outcomes, and transparency around program and credential value in the job market.

- Demand-driven differentiation for institutions; pursuing comparative strengths in learner segments, program design, and fields of study, where there is demonstrated labour market demand.

- Permissive higher education policy to maximize room for innovation; through clear, outcome-oriented system goals, frameworks and metrics, rather than prescriptive requirements, processes, and input-oriented performance measures.

- A competitive lifelong learning marketplace for public and private providers; with public funding primarily following the learner so they can choose their learning pathway and find the institution that best supports them, and a greater emphasis on employer investment reflecting sizable private benefits.

- Cooperation among public universities and colleges; both to lay the foundations for rapid acceptance of new credentials through the development of common definitions and standards, and to compete as one united system in an increasingly national and global online learning marketplace.

- Sustainable, diversified finances for institutions; with policy and funding levers encouraging smart growth, innovation, and new revenue sources from the lifelong learning market.

Policy Recommendations

Though public higher education institutions in Ontario have a large degree of autonomy, the provincial government plays an important system stewardship role; holds a set of powerful policy, regulatory and funding levers; and commands the bully pulpit for agenda “signaling.” Using these levers, there are a number of areas where policy makers can catalyze a lifelong learning agenda, encouraging and enabling Ontario’s public universities and colleges to cater to working-age learners.

1. Continue improving LMI and expand its use as the foundation for a demand-driven system. The Ministry of Colleges and Universities has made progress in introducing a labour market information website with detailed profiles and outlooks on over 500 occupations, with other labour market statistics. As next steps, the province should:

- continue to improve regional and local labour market information;

- partner with private, non-government and academic providers to offer applied tools (e.g. real-time LMI, career pathways) to support use of LMI by employers, colleges and universities, and workforce agencies; and,

- begin to incorporate these LMI resources in performance funding models to encourage programming that is tied to areas of high demand in the labour market (e.g. directing learners to programs leading to jobs with strong provincial, regional or local 5-year job outlooks).

2. Continue with targeted investments to lay the foundations for short-duration credentials and lifelong learning opportunities. Policymakers at Queen’s Park have taken important supply-side action to support the development of the nascent market for lifelong learning, including funding a micro-credential pilot program.[34] The 2020 Ontario Budget announced a three-year, $60 million micro-credential strategy with an incentive fund to promote the development of new micro-credentials.[35] These initiatives will support institutions to develop the knowledge, experience and scale to shift to self-sustaining models in full competition with other providers.

3. Streamline university and college program approval requirements for short programs that respond to labour market demand. This should include greater institutional autonomy in fast-tracking new programs, and making in-program changes, where institutions can demonstrate they will meet employment, labour market and economic recovery objectives (e.g. supported by real-time labour market information, or endorsed by industry coalitions).

4. Use regulatory and funding levers to support a competitive, learner-focused, demand-driven marketplace for short-duration credentials and lifelong learning opportunities. The province’s funding framework currently does not provide support for certain part-time learners and programs under one year in length. Some advocate for amendments to the funding formula, in alignment with the SMA process, to support per-student funding for these part-time and short-duration programs. A preferable approach would be a model where funding flows to the learner rather than the institution. This would incentivize competition, innovation and outcomes among all providers, in the spirit of a performance-based system. The features of this demand-driven model should include:

- Addressing informational barriers: The initiatives through the Ontario government’s new micro-credential strategy would increase demand among learners, such as through a public awareness campaign and online portal of micro-credential opportunities.

- Need-based support through OSAP: The government, as part of the new micro-credential strategy, has announced that it will expand Ontario Student Assistance Program (OSAP) eligibility to students in “ministry-approved, quality-assured” micro-credentials, which presumably includes programs offered by both public and private providers.

- Robust quality assurance: Expansion of OSAP should be coupled with consumer protection measures, with an agile approval and quality assurance process for new programs, and ongoing assessment of quality and learner outcomes. The objective is to ensure that, for OSAP recipients, the value of the program or credential is greater than any debt they are taking on. This quality framework should include both new university and college short programs, as well as new and existing OSAP-eligible private career college offerings.

- Integration, expansion and simplification of financial aid: The government should be clear with learners about the stackability of OSAP financial support with other benefits, including the Canada Training Benefit and supports like Second Career through the Employment Ontario system. Over the medium-term, the government should consider reimagining its support through a new, transparent, transformative lifelong learning grant or voucher system, still targeted based on financial need.

5. Align provincial reform agendas in higher education and Employment Ontario to create better integration and cooperation between the two systems.

- As public institutions roll out shorter, demand-driven programs geared to working adults, leverage existing education and training spend through Employment Ontario programs (e.g. Second Career, Canada-Ontario Job Grant) to direct learners to these college and university programs.

- Direct the new regional workforce SSMs in their performance contracts to ensure employment and training services develop learning and career pathways that offer college and university options.

- Closely follow Fleming College’s progress as pilot SSM in Muskoka-Kawarthas region to assess if this college-led workforce development model could be a fit in other regions.

6. Incentivize system-wide or consortium initiatives. Provide financial incentives and encouragement, through the SMA process or between cycles, for the formation of system-wide or multi-school consortiums to take joint action in the lifelong learning marketplace. For example:

- common prior learning assessment standards for working adult learners, adapted from leading jurisdictions;[36]

- common micro-credential and competency frameworks developed and validated with industry;

- shared open access programs with multiple pathways to traditional academic credentials across participating institutions;

- exploration of skills- or competency-based education (CBE) learning models;

- freely-shareable, open licence content across institutions; and

- regional consortia of institutions developing shared offerings and back-office capacity (e.g. in the North or the Southwest of Ontario).

This should build on existing intermediaries and assets like eCampusOntario, the OntarioLearn platform and Contact North.

7. Establish a micro-credentialing and recognition ecosystem with employers. The development of new credentials alone is insufficient; Ontario needs to modernize its qualification system to include short credentials, particularly those that are credit-bearing. This will ensure that adult learners receive appropriate value in the labour market for newly acquired skills and knowledge, and that private sector and other employers can rapidly understand and recognize the alternative credentials they begin to see on CVs and in LinkedIn profiles. As noted in a recent paper by eCampusOntario, “innovation in digital credentialing and micro-certification has been hampered in Canada by lack of consensus over the goals, methods and even the terms used to describe these flexible learning and recognition practices.”[37]

Conclusion

Ontario’s post-secondary institutions can harness a range of flexible education models in an effort to meet growing demand from working-age lifelong learners who increasingly need to access training and upskilling opportunities for a changing labour market. Labour market disruptions caused by the ongoing pandemic will only serve to accelerate this trend.

More broadly, Ontario’s long-term prosperity requires new and bolder approaches that address educational needs across the skills continuum and complement the development of resilient industries in the Ontario economy. The provincial government’s expanding stewardship role in higher education and workforce, and the investments in the 2020 Ontario Budget, are a promising start. But this moment demands new levels of boldness and imagination.

We are in a moment of opportunity for transformative education and workforce policy in Ontario; we must not let it pass us by.

André Côté is a public affairs consultant and serves on the Board of eCampus Ontario. Previously, he was senior advisor to Ontario’s Deputy Premier and minister for higher education and workforce policies, for Treasury Board, and for digital government. He has also held roles as COO with NEXT Canada; and as advisor to the Ontario Deputy Minister of Finance. Côté is a graduate of the Munk School’s Master of Public Policy program and Queens University.

Alexi White is a government relations specialist at the University of British Columbia. He previously served as a senior advisor to five Ontario cabinet ministers, including director of policy for the Minister of Education. His multiple roles in the Ontario Public Service included advising on online learning

and strategic mandate agreements in the Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities. White is a graduate of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and Queen’s University.

Michael Cuenco is a recent graduate of the Master of Global Affairs program at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. He has written on public policy issues in such publications as Policy Options, American Affairs, The Monitor and The American Conservative.

NOTES

[1] Statistics Canada, “The Daily: Labour Force Survey, October 2020,” November 6, 2020. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/201106/dq201106a-eng.htm.

[2] Advisory Council on Economic Growth, “Learning Nation: Equipping Canada’s Workforce With Skills For The Future,” December 2017. https://www.budget.gc.ca/aceg-ccce/pdf/learning-nation-eng.pdf.

[3] Desire2Learn, “The Future of Lifelong Learning,” 2020. https://www.d2l.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Future-of-Lifelong-Learning-D2L-2020-Digital-Edition.pdf.

[4] McMaster University, “Poverty and Employment Precarity in Southern Ontario,” 2020. https://pepso.ca/.

[5] Janet Lane and T. Scott Murray, “Literacy Lost: Canada’s Basic Skills Shortfall.,” Canada West Foundation, December 2018. https://cwf.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/2018-12-CWF_LiteracyLost_Report_WEB-1.pdf.

[6] Karen Myers, Kelly Pasolli and Simon Harding, “Skills-Training Reform in Ontario: Creating a Demand-Driven Training Ecosystem,” Ontario 360, November 2019. https://wp-a52btu2v90.pairsite.com/policy-papers/skills-training-reform-in-ontario-creating-a-demand-driven-training-ecosystem/.

[7] Daniel Munro, “Skills, Training and Lifelong Learning,” Public Policy Forum, March 2019. https://ppforum.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/SkillsTrainingAndLifelongLearning-PPF-MARCH2019-EN.pdf.

[8] Adapted from various sources including Strada Centre for Consumer Insights, which has been undertaking extensive surveying of Americans about education and work during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.stradaeducation.org/network/consumer-insights/

[9] Ryan Craig, “A New U: Faster + Cheaper Alternatives to College,” BenBella Books, 2018.

[10] Ontario Undergraduate Student Alliance, “Those Who Can, Teach,” January 2015. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/ousa/pages/109/attachments/original/1473430011/2015-01_Submission_-_Those_Who_Can__Teach_document.pdf?1473430011.

[11] Higher Education Strategy Associates, “The State of Postsecondary Education in Canada,” January 2020. https://higheredstrategy.com/the-state-of-postsecondary-education-in-canada-2/.

[12] PWC, “Fiscal Sustainability of Ontario Colleges,” January 2017. https://cdn.agilitycms.com/colleges-ontario/documents-library/document-files/2017%20Jan%20-%20Fiscal%20Sustainability%20of%20Ontario%20Colleges.pdf.

[13] Joe Friesen, “Ontario shelves plan for performance-based postsecondary funding, while Alberta pushes ahead,” Globe and Mail, May 6, 2020. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-ontario-shelves-plan-for-performance-based-postsecondary-funding/.

[14] The term “micro-credential” here refers to a category of short-duration credentials predominantly designed in partnership with industry that may or may not confer academic credit applicable toward longer programs.

[15] Higher Education Strategy Associates & The Strategic Council., “Micro-credentials: Mainstreaming Mid-Career Skills Development.” January 2020.

[16] Strada Centre for Consumer Insights, “Public Viewpoint: COVID-19 Work and Education Survey,” September 2020. https://www.stradaeducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Report-September-16-2020.pdf.

[17] Doug Lederman, “The biggest movers online,” Inside Higher Ed, December 17, 2019. https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2019/12/17/colleges-and-universities-most-online-students-2018.

[18] Steve Kolowich, “What Doomed Global Campus?,” Inside Higher Ed, September 3, 2009. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2009/09/03/what-doomed-global-campus.

[19] Doug Lederman, “Lessons Learned From a $75 Million Failed Experiment,” Inside Higher Ed, February 21, 2018.

[20] Interview with Gary Hepburn, Dean of the Chang School, October 7, 2020

[21] Western Governors University, “Faculty, Instructors, and Mentors,” October 7, 2020. https://www.wgu.edu/about/faculty.html

[22] Lindsay McKenzie, “Marketing for a Massive Online University,” Inside Higher Ed, October 8, 2019. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/10/08/how-marketing-helped-southern-new-hampshire-university-make-it-big-online

[23] Ontario Tech University, “University announces bold Ontario Tech Talent initiative to bridge the skills gap,” February 2020. https://news.ontariotechu.ca/archives/2020/02/university-announces-bold-ontario-tech-talent-initiative-to-bridge-the-skills-gap.php

[24] Keypath Education, “Wilfrid Laurier University Chooses Keypath Education as Online Program Management Partner,” August 2016. https://keypathedu.com/blog/2016/08/09/wilfrid-laurier-university-chooses-keypath-education-online-program-management

[25] Arizona State University, “Starbucks College Achievement Plan,” 2020. https://starbucks.asu.edu/

[26] Rebecca Koenig, “5 Years Since Starbucks Offered to Help Baristas Attend College, How Many Have Graduated?,” EdSurge, July 25, 2019. https://www.edsurge.com/news/2019-07-25-5-years-since-starbucks-offered-to-help-baristas-attendcollege-how-many-have-graduated

[27] Arizona State University, “ASU and Uber Education Partnership,” 2020). https://uber.asu.edu/

[28] Walmart,” Walmart’s New Education Benefit Puts Cap and Gown Within Reach for Associates,” May 30, 2018. https://corporate.walmart.com/newsroom/2018/05/30/walmarts-new-education-benefit-puts-cap-and-gown-within-reach-for-associates

[29] Desire2Learn,” FedEx Express and the University of Memphis Global,” November 29, 2019.

[30] Open Universities Australia, “Degrees and subjects”, 2020. https://www.open.edu.au/study-online/degrees-and-subjects

[31] Ontario Newsroom, “Ontario Moving Ahead with the Reform of Employment Services,” February 2020.

[32] Fleming College, “Fleming College receives multi-million-dollar contract to deliver prototype project for Employment Services in the Muskoka-Kawarthas region,” February 14, 2020. https://flemingcollege.ca/news/fleming-college-receives-multi-million-dollar-contract-to-deliver-prototype-project-for-employment-services-in-the-muskoka-kawarthas-region/.

[33] Alex Usher, “Performance-Based Funding 101: The Indicators. Higher Education Strategy Associates,” April 23, 2019. https://higheredstrategy.com/performance-based-funding-101-the-indicators/.

[34] ECampus Ontario, “eCampusOntario leads education-industry collaboration through micro-certification,” February 4, 2020. https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/ecampusontario-leads-education-industry-collaboration-through-micro-certification-808207332.html.

[35] Government of Ontario, “2020 Ontario Budget,” 2020. https://budget.ontario.ca/2020/index.html.

[36] Beverly Oliver, “Making micro-credentals work for learners, employers and providers,” Deakin University, August 2019. https://dteach.deakin.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/103/2019/08/Making-micro-credentials-work-Oliver-Deakin-2019-full-report.pdf.

[37] Don Present, “Micro-certification Business Models in Higher Education,” eCampusOntario, February 28, 2020. https://www.ecampusontario.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/microcert-business-models-en-v2.pdf.