Policy Papers

Transit-Oriented Communities: Why We Need Them And How We Can Make Them Happen

This paper, co-authored by University of Toronto professors Matti Siemiatycki and Drew Fagan, outlines the complex planning context regarding transit-oriented communities, including the Ontario government’s recently passed Transit-Oriented Communities Act.

Introduction

The recent Ontario budget reaffirmed the government’s major plans for infrastructure development, including a pledge to spend $145 billion over the next 10 years and a specific commitment to undertake significant investments in public transit. The budget describes such projects as a major part of the government’s overall plan to “stimulate future growth and job creation.”[1]

The government’s investments in public transit also are supported by a broader policy framework that underlines the importance of a more sophisticated coordination of transit development with community development under the policy rubric of so-called transit-oriented communities.

Recently passed legislation – the Transit-Oriented Communities Act – is aimed at reinforcing this policy agenda. But the act’s application, in the context of the four transit lines planned for the Greater Toronto Area, has quickly caused controversy. Queen’s Park’s plans for the high-profile Ontario Line, and especially two stops near downtown Toronto, are raising questions about what the legislation is meant to accomplish and how transit-oriented communities can be developed such that speed does not overwhelm fairness.[2]

All orders of government have policies in place to encourage effective development to take maximum advantage of transit planning. But what can be done to increase the odds of success, not just in terms of doing things fast but doing things well?

Transit-oriented communities are a key means of doing this. They co-locate housing, jobs, public amenities and social services near high quality public transit. This maximizes the public benefits that come from major investments in public transit. Increased ridership on transit systems is spurred by a planning process that encourages the location of housing and jobs nearby. This, in turn, cultivates healthy, sustainable, vibrant communities.

There is considerable interest in transit-oriented communities as part of post- pandemic recovery planning, in addition to the recent steps taken by the province.

Municipalities across the Greater Toronto region, including the City of Toronto, Mississauga, Brampton, Vaughan and Markham, are planning major transit- oriented communities, backed by some of the largest developers and institutional investors in the country.

The federal government also is a promoter of transit-oriented communities as part of a place-based strategy to use infrastructure to support community development. Rather than slowing uptake, the pandemic has redoubled interest in transit-oriented communities among all stakeholders, spurred by recognition that “building back better” requires more housing supply and more community services in healthy, walkable neighbourhoods.

But while there is widespread agreement on the merits of transit-oriented communities, it has been slow and difficult in Ontario to get them built. Development poses a particularly complex policy and implementation challenge. It is akin to solving a Rubik’s Cube. Like the damnably complex puzzle, the development of successful transit-oriented communities requires alignment among many government and private sector stakeholders, arranged in just the right order, at just the right time. This paper aims to provide a guide to solving this transit-oriented communities Rubik’s cube and in so doing help to inform the government’s implementation of successful transit-oriented communities.

- First, we set out the policy promise of transit-oriented communities and document the broad support that they have received from government and the private sector, particularly as part of the post-pandemic recovery effort.

- Second, we highlight the specific policy challenges of implementing transit- oriented communities. We outline the many public and private sector stakeholders involved in developing a transit-oriented community, showing the intersections of their responsibilities, resources and interests. We also identify the various policies that govern transit-oriented community development in Ontario.

- Third, we provide guidance on how to smooth the development of transit- oriented communities in Ontario. Guidance focuses on strategies to align stakeholder interests faster, to navigate inter-governmental dynamics more effectively, to help the public and private sectors work better together, and to create financing and funding mechanisms that catalyze effective community development.

Decision Context

Canada is still a car-dependent nation. Research by David Gordon at Queen’s University shows that two thirds of Canadians live in car-oriented suburbs, where the automobile is the primary mode of transportation. Greater Toronto is no different, with a dense urban core that supports high levels of walking, cycling and transit usage, surrounded by a vast ring of low density, car-oriented suburbs that are home to the majority of the region’s population.[3]

Over time, while car-oriented suburbs have provided many benefits to residents and become major places of employment, the high cost of car dependence has come into clearer focus. This includes long commutes, extreme traffic, air pollution, social exclusion of residents who do not drive, expensive lifecycle infrastructure costs, the paving over of natural habitats for urban uses, ill-health conditions beginning with a decline in physical exercise amongst residents, and traffic related accidents causing serious injury and death.

Transit-oriented developments are one key response to auto dependent cities. Successful transit- oriented developments are characterized by Robert Cervero and Kara Kockelman as encompassing in optimal balance the three Ds – density, diversity, and design. They are dense communities built within a 10 to 15 minute walking radius of rapid transit stations; they have a diversity of mixed land uses that encourages high transit ridership and a busy neighbourhood; and, they have high quality urban design and greenspace to draw people to the public realm.[4]

As early as 1990, under provincial government direction, development plans in the Greater Toronto Area were drawn up that boosted suburban growth but aimed to concentrate it in some 47 compact “nodes” to limit sprawl. The nodes would be dense, mixed-use hubs blending places to live, work and play, served by high quality rapid transit.[5]

Some nodes identified across the region were historic town centres, but many others were simply the sites of shopping malls surrounded by acres of parking, former industrial lands, or large parking lots adjacent to transit stations on the TTC subway and GO train network. Over the past 30 years, transit-oriented hubs have been the official policy of the provincial, regional and municipal governments of Greater Toronto.

The provincial Places to Grow regional growth plan and Metrolinx’s Big Move that date back about 15 years both mandate the concentration of growth in transit- oriented nodes. This strategic vision was reinforced by the 2011 publication of Metrolinx’s Mobility Hub Guidelines, which provides detailed urban form and design direction.[6]

More recently, the terminology at Queen’s Park has shifted from transit-oriented development to transit-oriented communities.

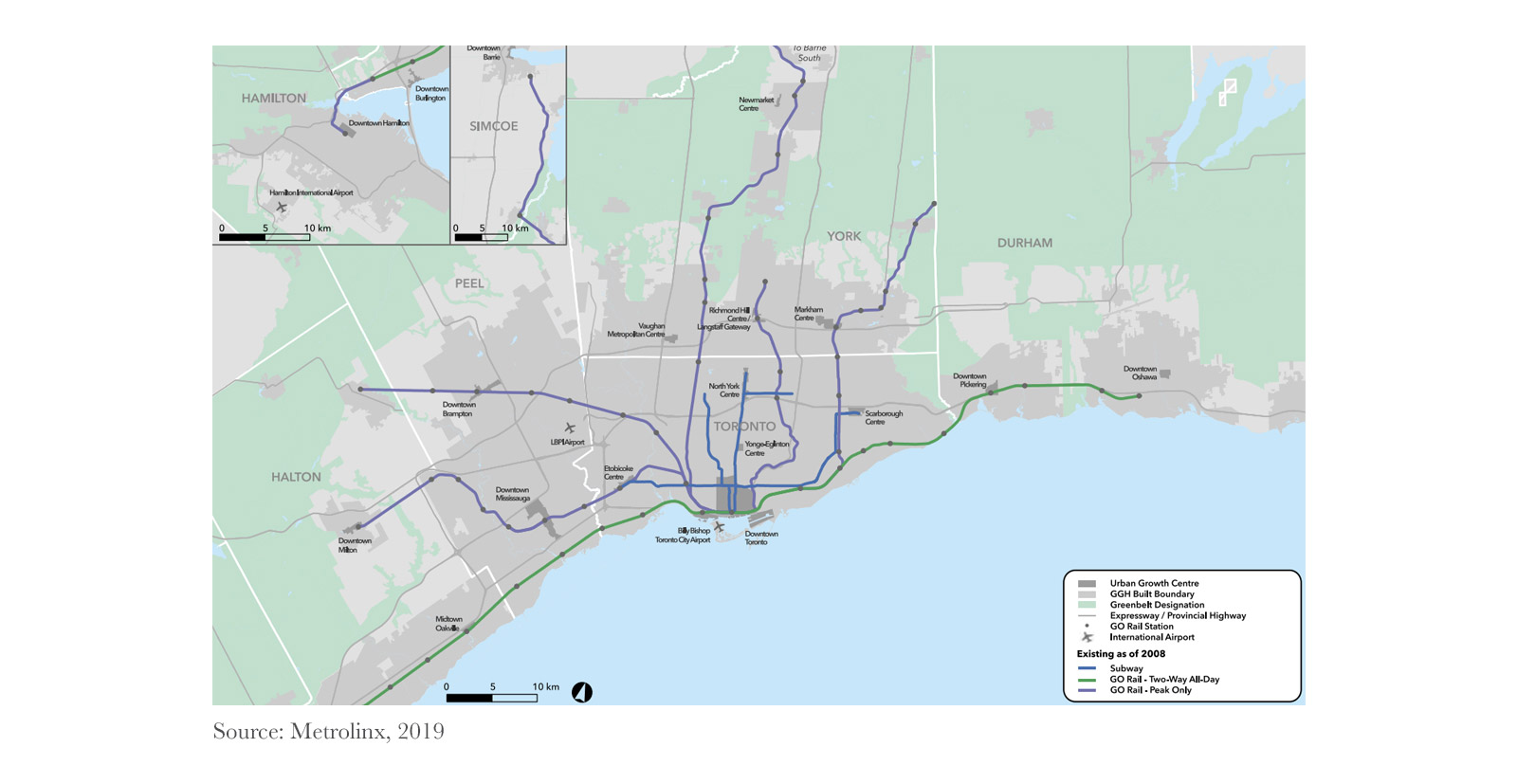

This subtle distinction highlights that the goal is not merely to spur any development adjacent to transit, but rather to create complete communities. In 2019, Metrolinx’s updated 2041 Regional Transportation Plan identified Urban Growth Centres throughout the region, committing that the “GTHA will have a sustainable transportation system that is aligned with land use, and supports healthy and complete communities.”[7] The updated 2020 Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe further prioritizes “intensification and higher densities in strategic growth areas.”[8]

The Transit-Oriented Communities Act has been described by government officials as a key step toward just this kind of development. But the act’s lack of detail – it is just six brief sections long – raises questions about the act’s intent, including the fact that it includes no definition of what might constitute a transit-oriented community beyond saying that it is a development project “of any nature or kind” connected to the planned transit lines. This means that the ultimate impact of the act just may be to clear the way toward faster development in which the first D (density) dominates at the expense of the other two Ds (diversity of land uses and design).

Figure 1: Greater Toronto Urban Growth Centres, Metrolinx 2041 Regional Transportation

Municipal official and secondary plans in Toronto, Oakville, Mississauga, Brampton, Vaughan and Markham all emphasize the concentration of growth in transit-oriented, mixed use communities. In Peel, the public health department has further reinforced this by creating the Healthy Development Assessment to support future developments that are “healthy by design.”[9] An emerging trend is for planning processes to develop community hubs at the heart of transit-oriented communities, which co-locate a mix of public schools, libraries, recreation centres, daycares, community services, and arts and culture facilities in the same building.

But progress has been slow, despite the consistent policy focus on catalyzing transit- oriented communities to deliver economic, environmental and social benefits. Some transit-oriented hubs have been built out and have thrived, most notably North York Civic Centre in Toronto. Development has also recently picked up at Vaughan Metropolitan Centre with the opening of a subway extension. But many other proposed hubs have remained largely fallow, or have experienced only a modicum of piecemeal residential development without the accompanying diversity of uses or quality of design that are critical to successful transit-oriented communities.

Even pre-pandemic, before transit ridership was decimated by lockdowns and social distancing, ridership growth in Greater Toronto had plateaued. Sprawling low density development continued at the edges of the region, making car-oriented suburbs some of the fastest growing communities. Meanwhile, Metrolinx, one of the largest owners of parking spaces in North America, balked at redeveloping lots that would take away “park and ride” opportunities and raise the ire of commuters.

Still, there is momentum to accelerate the development of transit-oriented communities across Greater Toronto, even as analysts wonder about the impact of the pandemic on urban population growth.

This can be explained by at least four factors.

First, Greater Toronto is in the midst of the largest wave of rapid transit development in a generation. All orders of government are making massive investments in transit as part of a pandemic recovery strategy to create jobs, lower greenhouse gas emissions, and improve equity, including in access to high quality transit. These major investments – including the four high-profile subway and light rail transit initiatives specified in the Transit-Oriented Communities Act — create new transit station nodes across the City of Toronto and into the surrounding region that can be used to develop transit-oriented communities.[10]

While it may seem counterintuitive to invest so heavily in transit at a time when there is such uncertainty regarding cities, transit investments and the benefits that they bring have multi-decade time horizons. Over the long-term, there is every expectation that Greater Toronto will continue to grow and depend increasingly on high quality rapid transit as the backbone of a thriving region.

Second, the pandemic has revealed the importance of complete communities that provide within close walking and cycling distances easy and safe access to quality jobs, green space, and all the necessities of daily life. The proposal of the Mayor of Paris to build “15-minute neighbourhoods” as a form of urban resilience for residents post-pandemic has captured global attention and is inspiring development plans globally, including here. In Ontario, municipalities have inserted a mandate to build 15-minute neighbourhoods into their official plans; Ottawa is a key example of this. Again, the goal is to improve local quality of life and cut down on the need for long commutes and expensive infrastructure.

Third, the Ontario government is pushing for dense development at transit stations. The province is especially interested in using such development to help to fund the cost of expensive infrastructure and increasingly is using its planning powers to expedite and boost the scale of development.

In 2019, for instance, the Province of Ontario and the City of Toronto signed a memorandum of understanding that Queen’s Park would take a leading role in development planning around the four transit projects mentioned previously.[11]

This was followed, in 2020, by passage of the Transit-Oriented Communities Act. The Act, as noted previously, appears aimed primarily at speeding up developments connected to stations on the four priority transit lines by giving the province enhanced powers to take control of potential development projects, to expropriate land more easily, and to enter into partnerships with external organizations and other government agencies to undertake development.[12]

The provincial government has also, more particularly, used Ministerial Zoning Orders to take greater control of development decisions. The ostensible rationale is to increase the speed of development decisions for both transit oriented and sprawling developments. The use of MZOs has raised community concerns about a lack of consultation and accountability. Taken together, the provincial government’s recent legislative agenda has been geared towards accelerating development, with a particular focus on density near priority transit lines.

Fourth, a new class of institutional investors with deep pockets is backing the current wave of transit-oriented communities. Many of the key sites designated for large- scale transit-oriented communities in the region, such as suburban shopping malls, post-industrial sites, and parking lots adjacent to rapid transit stations are owned by some of the largest institutional investors globally.

This includes the OMERS and AIMCo pension plan ownership of Square One Shopping Centre in Mississauga and the Scarborough Town Centre mall in the City of Toronto; the Public Sector Pension Investment Board’s purchase of the Downsview airport property; RioCan’s ownership of the Brampton Shoppers World mall; SmartCentres’ major land holdings around the Vaughan Metropolitan subway station; and the Remington Group’s role leading the redevelopment of Downtown Markham. These investors have the three fundamental ingredients to carry out major urban redevelopment projects at scale – land, money and expertise — and are moving to maximize the long-term value of their real estate holdings by betting on and driving development of dense, mixed-use, transit-oriented communities.

Decision Considerations

Why has it been so difficult to develop transit-oriented communities in the Greater Toronto Area if they have been a central feature of regional plans and public policy for more than three decades?

While momentum is building for such developments, there remains a risk that, in the absence of further policy considerations, they may not foster complete or equitable communities. In order to provide meaningful policy recommendations, it is first necessary to delve into the barriers that have stymied transit-oriented communities in the region.

Multiple actor problem: While conceptually simple and appealing, the actual delivery of transit-oriented communities requires coordination across an incredibly wide range of urban stakeholders.

Ontario municipalities, through their planning and development departments, typically control land use planning and approvals. Library boards, parks boards, and arts and culture institutions all have their own governance and funding models.

The provincial government is also made up of multiple ministries and agencies that have a hand in building transit-oriented communities – Ministry of Transportation and Metrolinx, Ministry of Infrastructure and Infrastructure Ontario, Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (which is increasingly engaging in local land use planning through Ministerial Zoning Orders), Ministry of Environment, Ministry of Education and its school boards, Ministry of Economic Development. The list goes on.

And the federal government has multiple points of engagement regarding transit infrastructure. It is primarily a funder of provincial and municipal transit infrastructure through the 12-year, $180 billion Investing in Canada infrastructure program that is administered by Infrastructure Canada, with additional input from numerous other departments, include Finance Canada. The Canada Infrastructure Bank also has a stream of funding to support revenue generating transit infrastructure projects, while Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation administers the National Housing Strategy to build safe, affordable housing.

Beyond the public sector participants, developers play a leading role in building and financing transit-oriented communities. While some large sites are owned by a single firm, many areas adjacent to transit stations have fragmented ownership that can be complicated to assemble and coordinate for development. And non-profit organizations often own and operate affordable and supportive housing nearby, as well as a myriad of community services.

This is a fragmented ecosystem with many actors who must navigate strategic and timing alignment to move projects forward. Even if there is general policy consensus on the benefit of transit-oriented communities, there are few formal or informal mechanisms or venues to convene the multiple stakeholders to find common ground and to chart a forward path regarding specific sites. Instead, each one must chart its own path to approval.

Long time horizons: Projects can stretch for decades, from initial planning and approvals through construction of multiple phases of a project. These prolonged processes add significant construction costs which have been escalating by nearly 8% per year in Greater Toronto for housing construction. They also add political risk and uncertainty.[13] In such circumstances, plans for transit-oriented communities must be strong enough to sustain changes in political leadership and among civil service staff. They must be able to weather economic ups and downs. And they must be sufficiently adaptive to survive changing trends in city building and urban life, such as the uncertainty regarding the balance between work-from- home and back-to-the-office after the pandemic.

Funding for community infrastructure: Funding formulas for key community elements like schools and parks often follow rather than lead urban growth. It can therefore be difficult to provide the social services that are at the core of a complete transit-oriented community. CityPlace in Toronto near the waterfront provides a case in point. The showpiece park was only built in 2009, years after many residents had moved into the area, and the school, community centre and library only opened in 2020, once sufficient development charges had been collected and a large population was in place. For almost a preceding generation, high quality public services could only be found outside the community. As master planned transit-oriented communities develop thousands of residential units and workplaces, there will be money available from development charges and other fees to fund the capital costs of public infrastructure. But there is also certain to be a timing problem to match infrastructure with communities as they grow, to ensure that they thrive – at least without consideration of policy reforms and greater focus on this mismatch.

Building mixed-use communities: The construction of 15-minute neighbourhoods is easier said than done. Market forces have historically meant that large master planned communities have favoured small residential units. Larger family sized units depend heavily on the availability of public infrastructure such as schools and community centres to entice developers to build them and can be expensive. The need for new partnership models is all the more important to encourage a mix of rental and housing ownership types at affordable prices. Additionally, the market has tended to favour residential buildings over offices or other major employment uses in most transit-oriented communities. This can challenge the diversity of uses that is necessary to provide jobs nearby and enable residents to avoid long commutes. Government policy and regional land use planning reform is necessary to create the conditions for truly 15-minute neighbourhoods to thrive.

Catalysts of inequality: A more recent concern involves the extent to which transit-oriented development spurs gentrification and displacement of existing communities. As new transit is built to provide improved mobility for people in low income, racialized and newcomer communities, development pressure mounts. There is a risk of displacement of small local retailers, for example, who often provide the kinds of ethnic foods and services that reinforce strong communities. With residents and cherished businesses facing displacement by redevelopment, communities can be irreversibly damaged. Across Greater Toronto – in Little Jamaica along Eglinton Avenue, at Jane and Finch in Toronto’s northwest, and along Hurontario in Mississauga – communities are mobilizing to fight gentrification and displacement.

The institutional investors leading major transit-oriented developments in Greater Toronto are in many cases the pension funds of government workers and are sometimes seen as the kinder face of capitalism. But critics also contend that some institutional investors have not been friendly to low-income tenants. Research by Martine August at the University of Waterloo shows how some

Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) have used various techniques to raise rents and maximize returns for investors from their rental buildings.14[14] Without careful planning and astute public policy, 15-minute neighbourhoods may not achieve the promise of being mixed income, inclusive communities.

Policy Recommendations

As shown above, while momentum is building for transit-oriented communities, care and collaboration are required so that all three Ds occur in a balanced fashion, ensuring development of the kind of living environments that people want – people from all strata.

Ontario is in the midst of the most significant period of rapid transit investment in a generation. This needs to be accompanied, as is the official public policy goal, by the encouragement and development of thriving transit-oriented communities that combine density, diversity of land uses, and high-quality design. While the impetus to move quickly is understandable given how long it has taken to build transit in the past, Bent Flyvbjerg highlights how rushed planning to get shovels in the ground is a major cause of mega-project disasters.[15]

In recent media interviews providing an update on the province’s transit-oriented communities program, Ontario’s associate minister of transportation Kinga Surma has recognized the importance of extensive cooperation among governments and involving community consultation to achieve effective outcomes.[16]

Along these lines, more can be done to increase the odds of widespread success, beginning with steps by the provincial government to clarify the intent of the Transit-Oriented Communities Act. The province should consider providing greater detail on its vision of a transit-oriented community in the context of the three Ds of density, diversity and design. Unless a balanced approach is specified, Queen’s Park is bound to run into further municipal opposition to its plans to support dense construction, as noted previously regarding Ontario Line stations. Transit-oriented communities are unlikely to reach fruition without a more open approach, to wit:

1. Create New Venues for Collaboration:

Collaboration and coordination are critical to the successful development of transit-oriented communities. But the Ontario governance landscape for transit and land use policy is deeply fragmented and, as controversy over the build-out of the Ontario Line shows, Queen’s Park’s efforts to move forward precipitously are unlikely to be viewed as being the same as moving forward effectively.

Better strategies are required to convene and coordinate the various public, private and non-profit players, even if this takes more time to achieve better outcomes.

- An intergovernmental Transit Oriented Communities Forum should be created to convene senior municipal, provincial and federal officials with a focus on coordinating transit and land use policy, as well as on funding programs necessary to boost development of affordable housing, long-term care facilities, schools and other public services. There now are few venues where officials from multiple orders of government and their many agencies can coordinate policy, resolve conflicting approaches and share best practices. The Forum could be established as an independent commission, or a member-based organization modeled on the National Executive Forum on Public Property that is housed at Queen’s University and includes members from all orders of government and various crown agencies.[17]

- More specifically regarding individual projects, the home municipality should convene a committee of the public, private, Indigenous groups and non-profit organizations that have a stake in each major transit-oriented community site. The role of the committee would be to provide the various organizations involved with a venue to share information and coordinate plans. Remarkably, such processes now are rare. The province could use the powers granted in the Transit-Oriented Communities Act to accelerate projects within the context of this collaborative framework.

2. Use all Available Policy Levers to Realize Social Value:

Government planners of transit-oriented communities should do all that they can to ensure that the transit-oriented communities built in Ontario are mixed income, multi-generational, multi-use, environmentally sustainable, and inclusive places to live, work and play. There are a variety of ways that governments can generate and recoup value from development activity toward this end. A critical policy tool is for governments to use density bonuses and land value capture techniques to recover a portion of the financial value of intensification to deliver community benefit. Hong Kong and Vancouver point the way with effective approaches to raise funds to offset costs of transit infrastructure and to support investments in community facilities. Additionally, municipalities can generate financial value by providing accelerated permits and approvals for transit-oriented communities in pre-selected areas, which reduces planning costs and avoids escalating construction costs. These strategies have been used in places like Bethesda, Maryland and Puget Sound, Washington, where stages of the development review process have been consolidated and permit applications simplified.[18] Municipalities also can reduce or eliminate minimum parking requirements for developments in transit-oriented hubs, which can substantially lower construction costs.

3. Develop Community Hubs at the Heart of Transit-Oriented Communities:

Community hubs are an emerging approach to provide quality public services that are critical to an inclusive transit-oriented community. Community hubs bring together anchor institutions at the heart of complete communities – such as schools, community centres, libraries, daycares, health care facilities, post- secondary campuses, and retailers. They provide complementary services but are governed and funded separately. By coordinating early in the development process, these institutions can find opportunities for co-location and collaboration that lower the costs of construction and operations and create opportunities for shared programming. With careful design, community hubs also can be built in an integrated fashion with housing, which creates a private revenue sources to offset some costs.

But to encourage community hubs, new government funding policies are needed such that they encourage coordination and anticipate the need for community facilities such as schools, which often now lag market-oriented development such as housing. The Canada Infrastructure Bank could be tapped to encourage investments in community hubs, with funds recouped through future development charges and tax revenues.

4. Engage Widely and Explore Innovative Models of Ownership and Governance:

Successful transit-oriented communities depend on extensive public engagement so that decision-makers understand the needs and desires of existing communities, which are often fearful of the gentrification that often comes with transit development. Pandemic restrictions on public gatherings have put limits on the types of in-person community town-hall meetings, open houses with display boards, and charettes that have been the typical format for public engagement. Yet the pandemic also has presented an opportunity to reimagine the way that public engagement is carried out using innovative virtual meeting formats, community surveys, on-site displays, and socially distanced in-person techniques to reach a wider range of participants than previously possible.

Along these lines, innovative models of mixed property ownership and governance should be integrated into transit-oriented communities, to leverage the value of development and to avoid runaway gentrification and displacement. Alongside private ownership, models to be explored can include public ownership of facilities like long-term care facilities and affordable housing, affordable housing co-operatives, and joint public-private developments with mixed ownership and governance. Funding for non-market forms of ownership can be generated from revenues recouped from additional building density, as well as from dedicated funding from senior orders of government.

5. Seek Intermediate Uses and High-Quality Design:

As noted previously, the building of large-scale, transit-oriented communities can stretch over decades. It is important in the context of project phasing to find approaches that benefit the community. Regarding shopping mall redevelopment, for example, it may not be necessary to close the entire site at once. Space can be provided to social service and arts organizations. Similarly, empty building sites can be repurposed as temporary community gardens, pop-up parks or spaces for festivals, as was done in the Helsinki district of Kalasatama (see sidebar). These “meanwhile spaces” create vibrancy and animate the public realm during a period of community transition.

More broadly, North American research shows that density on its own does not lead to complete communities or to high transit usage in transit-oriented developments. Rather, successful transit-oriented communities are realized through high quality design that boosts walkability and transit access. The basic qualities of transit-oriented communities, with all the necessities for daily life nearby, will become even more significant in a post-pandemic world.

Conclusion

Transit oriented communities are official government policy and have gained widespread support among public, private and non-profit players in the urban sphere as an optimal means of development, especially amid the stated goal to “build back better” in the post-pandemic context.

But as noted above, such development is much easier said than done in Toronto and the surrounding region. The complexity of planning and development processes, mixed with other incentives that often lean toward less socially beneficial development, continue to hinder progress.

The Ontario government appears intent to drive greater development along the four transit lines now planned for the Greater Toronto Area. This impulse is spot- on. But its recently passed Transit-Oriented Communities Act appears unlikely to spur the kind of balanced development envisaged by community planners and other advocates of transit-oriented communities. Queen’s Park should clarify the act’s intent, including in the context of the policy and process prescriptions suggested in this paper, which would help spur the laudable public policy goal of making urban living fairer and more dynamic.

Transit oriented development (TOD) is a concept that has been adopted across Canada and around the world. For a time in the mid 20th century, Toronto was recognized as a global leader in managing growth within a suburbanizing context, featuring prominently in Robert Cervero’s book The Transit Metropolis.[19] Nearly 70 years after the Yonge Street subway line opened, the route can be identified in aerial photos by the dense, high-rise mixed-use communities that have been built adjacent to most of the stations, strung like beads on a necklace.

But Toronto has struggled in recent years to concentrate growth and to realize well-designed development near many stations on the city’s subway and GO train lines, while other cities have evolved and innovated the implementation of transitoriented communities, using a variety of strategies.

Nordic cities like Copenhagen and Stockholm have continued for decades to advance growth containment plans that focus development and public amenities in compact, unique neighbourhoods near metro and suburban rail stations.[20]

In Helsinki, master planning for a new transit-oriented community in the old port district of Kalasatama was advanced and shaped by investing in high quality public facilities like a school early in the 25 year build out of the regeneration project. Pop up parks and festivals were also organized to enliven the area early on while it was in the process of being redeveloped.[21] In Singapore, city-scale master planning has combined targeted development into outer areas beside transit, with policies like road charging and caps on new vehicle registrations to limit car ownership and usage. Hong Kong is renowned for its rail plus property model (R+P). In this approach, the government grants the MTR transit agency permission to develop at stations and railyards on proposed lines. The MTR then partners with private developers to build housing, offices, retail and other public amenities on the land, and receives a portion of the profits. The MTR uses profits from development to offset the costs of building and operating the transit system, while station-area developments drive high transit ridership.[22]

And in Canada, Vancouver has been widely recognized as a leader in fostering transit-oriented communities. The regional transit agency TransLink partners with local municipalities and the private sector to develop transit-oriented communities that have a mix of densities, a wide variety of public and private amenities, high quality design and are walkable. In one unique example, TransLink and the City of Richmond have partnered to deliver the first fully privately-funded rapid transit station on the region’s system. In 2012, Richmond began collecting funds from developments in the proposed Capstan station area in exchange for additional density bonuses. It took some five years to collect sufficient revenues to fund the new station, and following planning and construction the new station is expected to enter service in 2023.[23]

Synthesizing the experience from a large number of case studies, research by Ren Thomas and Luca Bertolini illustrates the factors that are critical to the success of transit oriented development: national political stability, a regional planning body that coordinates transportation and land use, close relationships among the many players involved in development, project teams that work across disciplinary boundaries, and extensive public engagement to inform the project and build community support.[24]

Matti Siemiatycki is Interim Director of the School of Cities and Professor of Geography and Planning at the University of Toronto.

Drew Fagan is a professor at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy and a former Ontario deputy minister.

NOTES

[1] Government of Ontario, Ontario’s Action Plan: Protecting People’s Health and our Economy, 2021 Ontario Budget. https://budget.ontario.ca/2021/pdf/2021-ontario-budget-en.pdf.

[2] Toronto Star, April 12 and 13, 2021 (“‘Union Station to the east’ included in Ontario Line plan” and “Councillors balk at plans for five high-rise towers hidden in province’s plan for Ontario Line transit hub).

[3] Gordon, D. (2018). Still Suburban? Growth in Canadian Suburbs, 2006-2016. Council for Canadian Urbanism Working Paper #2. http://www.canadiansuburbs.ca/files/Still_Suburban_Monograph_2016.pdf.

[4] Cervero, R. and Kockelman, K. (1997). Travel demand and the 3Ds: Density, diversity, and design.

Transportation Research: Part D. 2(3), 199-219.

[5] Filion, P. (2003). Towards Smart Growth? The Difficult Implementation of Alternatives to Urban Dispersion. Canadian Journal of Urban Research. 12(1), 48-70.

[6] Metrolinx. (2011). Mobility Hub Guidelines. http://www.metrolinx.com/en/docs/pdf/board_agenda/20110218/MobilityHubGuidelines_optimized.pdf.

[7] Metrolinx. (2019). 2041 Regional Transportation. iv. http://www.metrolinx.com/en/docs/pdf/board_agenda/20110218/MobilityHubGuidelines_optimized.pdf.

[8] Ontario. (2020). A Place to Grow: Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe. https://files.ontario.ca/mmah-place-to-grow-office-consolidation-en-2020-08-28.pdf.

[9] Region of Peel. (2016). Healthy Development Assessment. https://www.peelregion.ca/health/resources/healthbydesign/pdf/HDA-User-Guide-Jun3-2016.pdf.

[10] To be certain, it is not too late for the province to revisit its priority projects. At least two of the four have Metrolinx authored business case studies from before the pandemic showing that they will not deliver value for money as currently designed. Both the Scarborough subway and the underground Eglinton West LRT should be replaced with surface LRTs. This point has been debated at length and change is unlikely.

[11] Province of Ontario-City of Toronto Memorandum of Understanding on Transit-Oriented Development. https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2020/ex/bgrd/backgroundfile-141912.pdf.

[12] https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/20t18 ; the province also passed the Building Transit Faster Act in 2020, further reinforcing speed of delivery as its top priority.

[13] Statistics Canada. (2020). Building construction price indexes. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210204/t001a-eng.htm.

[14] August, M. (2020). The financialization of Canadian multi-family rental housing: From trailer to tower. Journal of Urban Affairs. 42(7), 975-997.

[15] Flyvbjerg, B. and Gardner, D. (2021). “For infrastructure projects to succeed, think slow and act fast,” Boston Globe. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/04/01/opinion/bidens-transportation-projects-succeed-think-slow-act-fast/.

[16] https://www.thestar.com/politics/provincial/2021/04/12/province-plans-new-transit-hub-for-ontario-line-including-a-union-station-to-the-east.html

[17] For more information on the National Executive Forum on Public Property, see: https://publicpropertyforum.ca/

[18] Goodwill, J. and Hendricks, S. (2002). Building Transit Oriented Development in Established Communities. Centre for Urban Transportation Research. https://www.nctr.usf.edu/pdf/473-135.pdf

[19] Cervero, R. (1999). Transit Metropolis. Washington D.C. Island Press.

[20] See: Sørensen, E. and Torfing, J. (2019). The Copenhagen Metropolitan ‘Finger Plan’: A Robust Urban Planning Success Based on Collaborative Governance. In Great Policy Successes. Eds. P. Hart and M. Compton. Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online; and Pojani, D., & Stead, D. (2018). Past, Present and Future of Transit-Oriented Development in three European Capital City-Regions. In Y. Shiftan, & M. Kamargianni (Eds.), Preparing for the New Era of Transport Policies: Learning from Experience (pp. 93-118). (Advances in Transport Policy and Planning; Vol. 1). Elsevier.

[21] City of Brampton, Getting to Transit-Oriented Communities: Virtual Workship. https://www.brampton.ca/EN/City-Hall/Uptown-Brampton/Documents/October%202%20-%20ULI%20TOC%20Virtual%20Walkshop%20-%20ALL%20Slides.pdf

[22] Leong, L. (2016). The ‘Rail plus Property’ model: Hong Kong’s successful self-financing formula. McKinsey and Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/operations/our-insights/the-rail-plus-property-model#

[23] See: https://engagetranslink.ca/capstan-station-engagement;

[24] Thomas, R. and Bertolini, L. (2017). Defining critical success factors in TOD implementation using rough set analysis. Journal of Transport and Land Use. 10 (1), 139-154.