Policy Papers

Supporting Ontario’s Fiscal Strategy

Kevin McCarthy and Sean Speer outline how to support Ontario's ambitious fiscal agenda.

Summary of Recommendations

- Incorporate the federal experience with Strategic Reviews into the multi-year planning process in order to increase the incentives for government-wide buy-in for controlling or limiting the growth of program spending.

- Ensure the four conditions or ingredients for successful government transformations – namely, (1) clear metrics and benchmarks, (2) technology and project management capacity, (3) conservative saving estimates, and (4) cybersecurity risk mitigation.

- Leverage government decentralization to achieve efficiencies and support economic activity in rural and economically distressed parts of the province.

Introduction

The Ontario government’s recent Fall Economic Statement updated Ontarians on the government’s fiscal projections and in so doing recalibrated its overall fiscal policy.

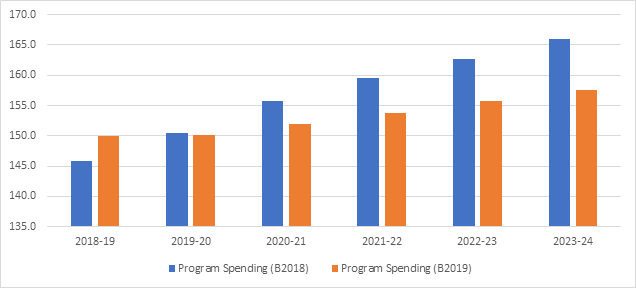

The government came to office with an ambitious fiscal agenda. The 2019 budget, for instance, spoke of the need to “restore [fiscal] balance before it hurts the economy, jobs, and the people who depend the most on critical government services every day.”[1] It in turn adjusted projected program spending downward by $21 billion between 2018-2019 and 2023-24 relative to the 2018 budget (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1: COMPARISON OF PROJECTED PROGRAM SPENDING, 2018-19 TO 2023-24, BUDGET 2018 AND BUDGET 2019 ($MILLIONS)

Source: Ministry of Finance, 2018 Ontario Budget: A Plan for Care and Opportunity. https://budget.ontario.ca/2018/budget2018-en.pdf; and Ministry of Finance, 2019 Ontario Budget: Protecting What Matters Most. https://budget.ontario.ca/pdf/2019/2019-ontario-budget-en.pdf.

This fiscal adjustment reflected the cumulative effects of the Ford government’s multi-year planning process which sought to constrain spending growth in order to achieve budgetary balance. It was a combination of top-down and bottom-up efforts that basically involved ministries receiving expenditure ceilings from the central agencies and then reporting to a select committee of the Treasury Board on the policy choices that would enable them to live within their respective caps. The resulting decisions were then effectuated in the 2019 budget’s overall spending projections.

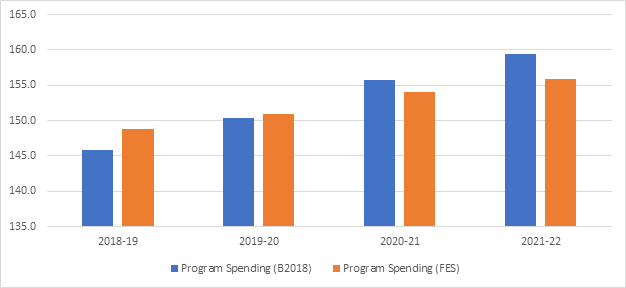

The 2019 Fall Economic Statement has made further adjustments to the government’s spending projections. These adjustments were mostly upward revisions due in part to new spending priorities and in part to revisiting some of the policy decisions from the multi-year planning process. The revised spending track is still more ambitious than the 2018 budget but less than the recent one. The Fall Economic Statement’s spending projections are $2 billion less than the 2018 budget but $3.8 billion more than the 2019 budget for the period from 2018-19 to 2021-22 (see Figure 2).[2]

FIGURE 2: COMPARISON OF PROJECTED PROGRAM SPENDING, 2018-19 TO 2021-22, BUDGET 2018 AND 2019 FALL ECONOMIC STATEMENT ($MILLIONS)

Source: Ministry of Finance, 2018 Ontario Budget: A Plan for Care and Opportunity. https://budget.ontario.ca/2018/budget2018-en.pdf; and Ministry of Finance, 2019 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review: A Plan to Build Ontario Together. https://budget.ontario.ca/2019/fallstatement/pdf/2019-fallstatement.pdf.

Notwithstanding these adjustments, the government remains committed to its medium-term fiscal plans. As the Fall Economic Statement notes: “We will continue to implement our prudent and responsible approach to fixing our finances, balancing the budget by 2023, so that we can make critical investments and provide relief for families and businesses.”[3]

The purpose of this short paper is to help the government stay on track. The goal is to help inform and shape the Ford government’s fiscal planning as aims to deliver on a balanced budget by 2023. The paper draws on our personal experiences in the federal government as well as a body of research to set out some principles and processes to guide fiscal policy in Ontario. Our main observation is that deficit reduction requires a two-fold effort: (1) control the growth of new spending and (2) improve pre-existing spending. The Ford government’s fiscal planning and policy requires this one-two punch if it is to ultimately deliver on its budgetary commitments.

Ontario’s Current Fiscal Picture

It is worth starting this analysis with a refresher on Ontario’s fiscal picture. A 2018 paper by Livio Di Matteo for Ontario 360[4] provides a good primer on where the province’s budgetary position stands and how it got here.

The Ontario government’s fiscal bias has been in favour of deficit spending for the past 40 years. It has run deficit more than 80 percent of the time since 1980.

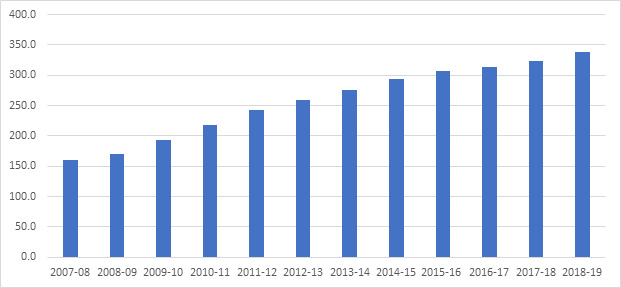

The current run of deficits which started in 2007-08 is only the most recent iteration. But it is also unique because of the heavy debt load that has accumulated over this period. Annual deficits have added $107.3 billion in accumulated debt and in turn raised the province’s total net debt to 338.5 billion in 2018-19 (see Figure 3). It is set to hit $353.7 billion this year.[5]

FIGURE 3: ONTARIO NET DEBT, 2007-08 to 2018-019 ($MILLIONS)

Source: Department of Finance, Fiscal Reference Tables, 2019. https://www.fin.gc.ca/frt-trf/2019/frt-trf-19-eng.pdf.

This amounts to an 80-percent increase in net debt per capita from $13,363 in 2008-09 to $23,979 in 2018-19.[6] It is no surprise therefore that the province’s debt-to-GDP ratio is now the highest in the country (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 4: NET DEBT-TO-GDP RATIO BY PROVINCE, 2019-20 (%)

Source: Ministry of Finance, 2019 Ontario Budget: Protecting What Matters Most. https://budget.ontario.ca/pdf/2019/2019-ontario-budget-en.pdf.

A series of credit downgrades between 2009 and 2018 signaled that the government’s structural deficit and heavy debt accumulation were not sustainable over the long-term. Reports by the Parliamentary Budget Office[7] and Financial Accountability Office of Ontario[8] only confirmed it.

The incoming government therefore launched a series of steps to better control spending and put the province’s fiscal trajectory on a more sustainable path including an independent fiscal commission, a line-by-line spending review, and a more rigorous multi-year planning exercise. We will discuss the multi-year planning process in the next section.

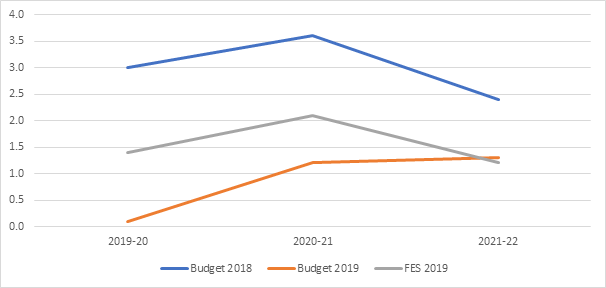

Budget 2019 effectuated these changes as well as adjustments to provincial accounting for energy-related revenues and expenditures. The net effect was a considerable reduction in projected program spending relative to the 2018 budget and improvements to its deficit projections. The budget did not enact a net reduction in spending. It was more about adjusting downward the growth in program spending relative to its predecessor’s plan. It is important to note that the 2018 budget’s baseline (which projected spending growth of 6.1 percent in 2018-19 and an annual average of 4.3 percent between 2018-19 and 2020-21) was inflated even for the previous government. (see Figure 5).

FIGURE 5: ANNUAL PROGRAM SPENDING GROWTH, 2019-20 TO 2023-24, BUDGET 2018 AND BUDGET 2019 (%)

Source: Ministry of Finance, 2018 Ontario Budget: A Plan for Care and Opportunity. https://budget.ontario.ca/2018/budget2018-en.pdf; and Ministry of Finance, 2019 Ontario Budget: Protecting What Matters Most. https://budget.ontario.ca/pdf/2019/2019-ontario-budget-en.pdf.

As discussed earlier, the recent Fall Economic Statement made some adjustments to 2019 budget’s spending projections. It did not ratchet back to the 2018 budget’s levels. But average annual growth in program spending has doubled relative to the 2019 budget for the period between 2019-20 and 2021-22 (see Figure 6).

FIGURE 6: PROJECTED PROGRAM SPENDING, 2019-20 TO 2021-22, BUDGET 2018, BUDGET 2019 AND FALL ECONOMIC STATEMENT 2019 (%)

Ministry of Finance, 2018 Ontario Budget: A Plan for Care and Opportunity. https://budget.ontario.ca/2018/budget2018-en.pdf; Ministry of Finance, 2019 Ontario Budget: Protecting What Matters Most. https://budget.ontario.ca/pdf/2019/2019-ontario-budget-en.pdf; and Ministry of Finance, 2019 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review: A Plan to Build Ontario Together. https://budget.ontario.ca/2019/fallstatement/pdf/2019-fallstatement.pdf.

The trend line is still much better than what the current government inherited. But the changes in spending growth between the 2019 budget and the Fall Economic Statement are a reminder of the inherent risks of budget planning. That program spending in 2019-20 is now largely unchanged between the 2018 budget and the 2019 Fall Economic Statement – $150.4 billion versus $150.9 billion (which amounts to a 0.3 percent difference) – is a sign that the government cannot fall victim to fiscal complacency if it ultimately wants to deliver on its budgetary goals. It is notable for instance that spending projections are revised upwards in immediate years and downwards in the medium-term. Near-time adjustments invariably lead to longer-term adjustments if a government is not careful.

The Next Phase of Multi-Year Planning

The government used a multi-year planning process in the 2019 budget cycle to identify potential fiscal savings. As the 2018 Fall Economic Statement explained: “the goal is to ensure each program, ministry, and the government overall, is doing everything it can to deliver results for the people of Ontario in a responsible and sustainable way.”[9]

Ministries were given expenditure ceilings and expected to report to a select committee of the Treasury Board on the policy choices that would enable them to live within their respective caps. One might think of it as a variation of “zero-based budgeting.”[10] The decisions were then effectuated in the 2019 budget.

Last year’s goal was principally about realizing fiscal savings for the purposes of deficit reduction. Most ministries were expected to live within new multi-year budgets that were lower than was projected in the 2018 budget. All were expected to identify administrative, non-programmatic savings of at least 4 percent.[11] Any resulting savings were used to offset the costs of new government priorities (such as the LIFT Tax Credit and new child-care benefit) or pay down the deficit. This is how the government was able to change accounting practices for energy-related costs, enact new priorities, and still lower the province’s deficit projections.

Now that the first year is complete, the government is maintaining the multi-year planning process. The recent Fall Economic Statement, in fact, confirmed that the process for 2020-21 is currently underway.[12] It is now less about identifying new or incremental savings and more about monitoring progress, making year-over-year adjustments (based on revisions to spending plans), and prompting ministries to consider trade-offs between new priorities and existing spending in their respective budgets.

The underlying intention here is precisely right. A rigorous multi-year planning process was required last year to try to make progress on reducing pre-existing spending. An ongoing process is now needed to control and limit new spending. This requires a model that institutionalizes decisions about trade-offs and prioritization.

It is a mistake to assume that the $150 billion or so in annual program spending is a given and to only focus internal scrutiny on incremental spending. That is how unjustified or ineffective programs and spending become permanent and ultimately how the government grows.[13] It also creates an inherently centralized approach whereby Finance and Treasury Board are the sole gatekeepers and the other players in the system have no stake in the government’s overall fiscal objectives. The government’s multi-year planning process can therefore be reoriented from finding savings to enabling trade-offs, prioritization, and internal recycling that can limit the growth of new spending.

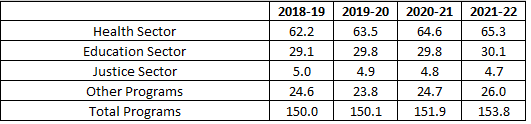

The model is especially important given the composition of provincial spending. Holding program spending constant is challenging in light of demographic pressures on health care. The 2019 budget is a good example. The Ford government sought to hold overall program spending to an annual growth rate of less than 1 percent while health-care spending was growing at an average rate of 1.6 percent. This necessarily puts pressure on other program spending areas including education and justice (see Table 1).

TABLE 1: ONTARIO PROGRAM SPENDING BY AREA, 2018-19 TO 2021-22, 2019 BUDGET ($MILLIONS)

Ministry of Finance, 2019 Ontario Budget: Protecting What Matters Most. https://budget.ontario.ca/pdf/2019/2019-ontario-budget-en.pdf.

Recognizing that health-care spending is bound to continue rise due to growing demand, it is crucial that the government have a system-wide process to make judgements about the relative utility and political prioritization of non-health spending. Something has to give. New spending proposals will need to be judged against pre-existing spending and a mechanism for internal recycling will be needed to enable fiscal offsets for new spending that ultimately goes ahead. The multi-year planning process can serve as a vehicle for such fiscal priority-setting.

As described above, it also can be used to create incentives for each minister and his or her ministry to play a role in the government’s overall fiscal objectives. Achieving the government’s fiscal targets cannot be the sole responsibility of the Minister of Finance and Treasury Board President. The entire government needs to internalize these objectives and participate in their progress. Yet some of the fiscal adjustments in the recent Fall Economic Statement risk diminishing the government-wide commitment to deficit reduction. It may signal to other ministers and ministries that constraints have been lifted. It is important therefore that the government use the multi-year planning process to reaffirm the govenrment-wide focus on limiting the growth of program spending.

Our Experience with Strategic Reviews

Here is where the role of incentives is key. There may be scope to refine the multi-year planning process to increase the incentives for ministries to fully participate in the government’s fiscal objectives by drawing on the Harper government’s Strategic Review process of which we were both apart.[14]

Strategic Reviews (which ran from 2007 to 2009) were not driven by a fiscal crisis or deficit reduction objectives. It was principally focused on controlling or limiting the growth of new spending by reallocating departmental spending from low- to high-priority initiatives. The exercise was stopped in the face of the global economic recession and has not since resumed. But its basic mandate and design could be incorporated into Ontario’s multi-year planning process.

Roughly 25 percent of government spending was reviewed annually over a four-year cycle. Participating departments in a given year were identified in the early spring. They were given a spending base and 5-percent target from the Treasury Board Secretariat and required to conduct a self-evaluation of where it could achieve these savings using of set of metrics including:

- Increase efficiencies and effectiveness: Do these programs and services deliver real results for Canadians and provide value for money?

- Focus on core roles: Are these programs and services aligned with the federal role or is another level of government or some other institution (such as the market or civil society) better placed to deliver them?

- Meet the priorities of Canadians: Are these programs focused on the needs and priorities of Canadians?[15]

The results of these reviews were presented to Treasury Board in the summer or fall in order to inform the budget process. But remember the goal was not necessarily to reduce spending as much as it was about controlling or limiting the growth of new spending. So while departments were required to identify their “lowest-priority, lowest-performing 5 percent of spending” for reallocation, they were also permitted to put forward alternative spending proposals for reinvestment.

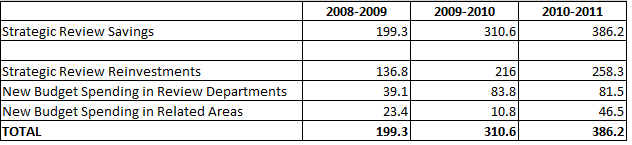

The 2007 experience is illustrative. Seventeen federal organizations (including departments and agencies) participated that year representing $13.6 billion in direct program spending or roughly 15 percent of all government program spending that was examined under strategic review.[16] The share was a bit lower that year because it was a new process. All identified savings were recycled back into the same departments or related areas (see Table 2). Basically the government was able to use the Strategic Review process to control the growth of new spending in these areas through fiscal recycling.

TABLE 2: FEDERAL STRATEGIC REVIEW PROCESS, 2007 ($MILLIONS)

Source: Treasury Board Secretariat of Canada, 2007 Strategic Review Results. https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/sr-es/res/res-2007-res-eng.asp.

That the identified savings were “reinvested” mostly back into the departments created an incentive for ministers and their departments buy into their exercise. They knew that their full participation provided the basis to partially or fully finance their new priorities.

This observation is not derived from a body of public administration scholarship, but it certainly reflects our own experiences and that of others who worked for the then Prime Minister or the then Finance Minister. A government can impose fiscal constraints on itself through a combination of public pronouncements and internal processes. But a system-wide commitment to limited new spending requires dedication and focus from the Cabinet and the governing caucus. It will not work if the Finance Minister and the Treasury Board President on their own. The Trudeau government’s four-year mandate seems to be evidence of this point.[17]

The Harper government’s fiscal objectives, by contrast, were not the sole purview of the Prime Minister, Finance Minister, or Treasury Board President. There was a sustained commitment by every minister to scrutinize his or her own spending and to prioritize any requests for new spending within the government’s broader agenda.[18] As we will discuss in the recommendations, we think there is an opportunity to incorporate the Strategic Review model into Ontario’s multi-year planning process.

Implementing the Smarter Government Initiative

If the multi-year planning process is principally about controlling or limiting the growth of new program spending, the Ontario government’s Smart Initiatives is about improving pre-existing spending.[19] This exercise is less about meeting centrally-set fiscal targets and more about improving the functioning of government and in turn providing better services at lower costs for Ontarians. As the Treasury Board President put it in an October 2019 speech: “[this initiative] will streamline and improve services, fix inefficiencies and build a government that’s responsive to you.”[20]

His remarks highlighted three initiatives that the government is advancing as part of the Smart Initiatives:

- Digital First – better utilizing technology to provide service delivery

- Transfer payment consolidation – streamlining the nearly 35,000 transfer payment arrangements the government currently has with universities, colleges, hospital, service delivery partners, and so on

- Smarter government purchasing – modernizing the government’s procurement policies and practices to leverage economies of scale

The Fall Economic Statement provided further information about the Smart Initiatives including the creation of a Value Creation Task Force involving various ministers and members of provincial parliament to identify possible non-tax revenue generation sources and an Agency Review Task Force to conduct reviews of arm’s-length agencies in order to identify efficiencies.

These various initiatives are positive. There is certainly scope to improve the operations and functioning of government. The line-by-line review, for instance, identified 35,000 unique recipients of transfer payments from the Ontario government and the transfer payment system as a key target for improvement.[21] Another interesting area is the Ontario government’s real property footprint. The Fall Economic Statement observes that 35 surplus properties have already been sold and, as we discuss in a subsequent section, there may be an opportunity to further decentralize the province’s footprint in the name of efficiency and regional equity.[22] The government has established a website to track progress on the Smart Initiatives exercise at www.ontario.ca/page/building-smarter-government-works-you.

Lessons From Successful Smart Government Initiatives

Ontario is not the first government to look to technology and process improvements to find efficiencies and improve service delivery. A review of the literature on such initiatives elsewhere, in addition to our own experiences in Ottawa, point to a set of conditions or ingredients that are associated with successful outcomes. We have identified four through our research and analysis.

- Evidence Based – clear metrics and benchmarks

- Technology and project management capacity

- Conservative saving estimates

- Cybersecurity risk mitigation

A 2018 report by the International Monetary Fund that examines the potential for digital government provides some useful insights for Ontario policymakers.[23] A 2014 report by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development similarly provides useful recommendations with respect to best practices for digital adoption within government.[24] These two reports (in addition to others by McKinsey,[25] the Obama Administration[26], and the UK government[27]) zero in on these four conditions or ingredients as key to how policymakers should think about transformation strategies. We would add that these conditions or ingredients are consistent with our own experiences in Ottawa where an administrative services review that ultimately led to email consolidation and payroll consolidation (known as the Phoenix system) has produced poor results. Let us unpack these four conditions or ingredients for success.

- Evidence-based decision making – Clear metrics and benchmarks

Any Smart Government Initiative must be evidence-based with clear metrics and benchmarks that not only enable policymakers and the public to determine success but even to make judgments about which areas to target. The good news is that various aspects of Smart Government Initiatives lend themselves to benchmarking.

Other governments and private sector firms have used a range of metrics to render judgments about similar internal improvements using technology and other best practices. Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, in particular, are three jurisdictions that a previous Ontario 360 commentary identified as leaders in this area.[28] The Ontario government can draw from these different experiences in order to identify the right priorities and learn the lessons of past failures.

The key point though is that rooting these decisions in clear metrics and benchmarks is key to both securing public support and achieving transparency and accountability. The creation of the website is a good step in this direction. The government should continue to communicate which Smart Initiatives are rolling out and the progress that they are making.

It is important to recognize, however, that not every initiative will be successful. Some will invariably fail. The government should precondition the public accordingly. The risk of failure cannot stymie experimentation or progress. Public servants and taxpayers need to understand what the government is aiming to achieve and that the political arm of government recognizes that not every initiative will necessarily be implemented without challenges or produce huge fiscal savings.

A focus on metrics and benchmarks is not cultivate cautiousness. Apple or Facebook or other sophisticated firms are not perfect. The Ontario government should not expect to be either. But rooting these decisions in metric and benchmarks and communicating their progress along these lines will help to build trust and confidence.

As part of an ongoing communication mechanism, the government should consider releasing a quarterly or annual Smart Initiatives report (possibly in conjunction with the Fall Economic Statement) that updates Ontarians on what is happening, what is working, and what is not. It should also offer to provide regular briefings to the opposition parties so that the parliamentary critics can see the business cases for different transformations and keep track of their status. This should about good governance rather than partisanship.

2. Technology and project management capacity

Most Smart Government Initiatives tend to involve a degree of digitization. That is to say there is considerable opportunity to modernize and improve govenrment programming and services by better utilizing digital and technological innovation.

Few would contend with this observation. One of us was recently involved in a review of Ontario’s Workplace Safety and Insurance Board and was struck to discover that it receives roughly 21,000 telephone calls and 6,000 faxes per day because individuals and firms have few other means to contact the organization.

But success is hardly guaranteed. It requires the appropriate level of project management and technological capacity within government to execute these digital transformations. A lack of capacity is a major contributor to poor vetting of proposals and then poor management of their implementation.

This is consistent with our own experiences. We both remember advising elected officials about complex transformation proposals and thinking we did not have the experience or capacity to advise on strengths and weaknesses of different proposals. It was also unclear that the elected officials or public servants had the capacity to make these judgments. When combined with an adequate focus on metrics and benchmarks, this question of capacity is key reason that certain initiatives can spectacularly fail.

The Treasury Board Secretariat’s Central Agencies I&IT Cluster’s group is, by all accounts, well-staffed and well-qualified to contributed to this exercise. The same goes for the Change Management and Digital Service groups within Cabinet Office.

But if the government is to be ambitious in its Smart Initiatives, it is going to require public service and political leadership. The current Executive Development Committee of Deputy Ministers, chaired by the Cabinet Secretary, is a great forum for different transformation proposals to face public service scrutiny before ultimately going to Cabinet. Similarly the government should ensure that these proposals are subject to Cabinet scrutiny at the highest level including the Premier. The key is to establish a clear and consistent process for how these proposals are scrutinized, approved, and monitored.

This cannot be perceived as just another government initiative. It will require structure, resources, staffing, and attention if it is to produce positive results and minimize political or operational risks. Queen’s Park cannot execute this agenda off the side of its desk and expect it to go well.

3. Conservative saving estimates

Governments are drawn to these types of initiatives in large part due to the potential fiscal savings. But that cannot be the overriding motivation. If a project does not make sense apart from the fiscal savings, then it is not worth pursuing.

We cannot stress this enough: The Smart Initiatives agenda cannot be narrowly focused on deficit reduction or fiscal savings. If it is, then it is set up to fail for two reasons.

The first is that most of these projects will require some short-term spending and may not produce savings until full implementation. It is unrealistic to think that ministries are going to assume these short-term costs given the inherent incentives in the multi-year planning process. There may be a need therefore to create a central funding envelope to defray any costs associated with transformation projects undertaken by different ministries. But this only reinforces the need for metrics and benchmarks because, if the government creates a central funding source, it will require some mechanism to judge which projects should proceed.

The second is that, for better or worse, our experience is that most transformation projects experience unexpected challenges that cause cost overruns or delays. Depending on these projects for deficit reduction is thus a risky proposition. We experienced this in Ottawa where we “booked” considerable savings stemming from email consolidation that ultimately failed to materialize and created a fiscal gap.

Ontario should not make the same mistake. It will not be easy, however. It can be challenging to risk the temptation to record savings from these initiatives. But it is important to choose the right projects and get them right than it is to save some incremental amount in the short-term.

4. Cybersecurity risk mitigation

While there are potential benefits from digital transformation projects, we would be remiss if we did not point out that the research and evidence highlights the potential cybersecurity risks. The potential for fraud, privacy concerns, data governance, and hacking must be part of any business case involving digital adoption. Increased dependence on digital connectiveness will invariably require investments in cybersecurity and developing plans and strategies to protect citizens’ data. Just think, for instance, of the potential consequences of a significant data breach.

Cyberattacks can lead to a disruption of essential services such as what happen in 2017 with the cyberattack on the National Health Service in the United Kingdom. This experience demonstrates how such attacks can disrupt the provision of public health care services.[29] Canada is not immune to this risk. We have had similar experiences in Ottawa where the National Research Council, Department of Finance, and others have been subject to cyberattacks in recent years.

The point is not to discourage the government to pursue digital or technology-adoption initiatives. But it is to flag that these cannot be evaluated narrowly along cost/benefit lines. The question of cybersecurity must also be evaluated. It is notable, for instance, that Estonia, which has 99 percent of its state services online, has invested significantly in a blockchain technology for its identification cards and has created an advanced digital identity system for user authentication after cyberattacks in 2007 froze its online services.[30] As the Ontario government undertakes its Smart Initiatives, it will need to consider what, if any, incremental steps will be needed to protect itself from data breaches and cyberattacks.

Potential for Government Decentralization

As mentioned earlier, there may also be a synergy between the government’s Smart Initiatives and its focus on rural and economically distressed parts of the province. Placing an emphasize on decentralizing the government’s real property and employment footprint could make progress in both areas.

The City of Toronto is both the most dynamic centre in the province and its seat of government. This seems counterintuitive for various reasons including (but not limited to) Toronto’s sky-high real estate prices. Rebalancing the province’s real property and employment footprint could thus ostensibly save taxpayers. But it could also provide reasonably stable and well-paying employment in parts of the province in need.

This seems like a win-win therefore. The only question is: how can the government go about implementing such a decentralization agenda?

A recent paper by the Brookings Institution provides some insights.[31] One of its key observations is that closer alignment between government and the regional or local economy could be highly beneficial. It could be a clustering effect whereby decision-making officials, business leaders, labour unions, and others could work together on industry-level or regional challenges.

The author, for instance, uses the U.K. government’s “decentralization” exercise in 2004, which aimed to move 20,000 public-sector positions out of Greater London and into economically depressed regions of the country, as a possible model that can be replicated in Ontario. Over the following ten years the government moved more than 25,000 jobs and subsequent research found that the relocated jobs had positive effects on local employment and economic activity.[32]

The Ford government, which has rightly identified regional economic disparity as a major challenge facing the province, should lean into a decentralization agenda. But it cannot just be about shuffling around public sector jobs. It needs to be careful and intentional. The lesson from other jurisdictions that there must a human resource capacity present and there should, to the extent possible, an industry-level or regional connection to the type of service.

But notwithstanding these caveats, given the growing urban/rural divide across the province, the Ontario government should embark on an ambitious decentralization agenda in order realize efficiencies and boost economy activity in rural and economically distressed parts of the province.[33]

Recommendations

The main takeaway from this research and analysis is three key policy recommendations.

1. Incorporate the federal experience with Strategic Reviews into the multi-year planning process in order to increase the incentives for government-wide buy-in for controlling or limiting the growth of program spending

The Ontario government’s multi-year planning process has served it well as a mechanism for achieving fiscal savings. But, as the government shifts to a greater focus on building system-wide buy-in to controlling the growth of program spending, there is room to refine the process in order improve the incentives for ministries to fully participate.

Incorporating the federal experience with Strategic Reviews could help to get ministers and their ministries to fully participate in exchange for being able to “reinvest” a portion or all of their identified savings.

Adopting such a model would not require wholesale change to the multi-year planning process. Every ministry would still come forward each year with year-over-year adjustments. But every two or four years (depending on the government’s ambition), every ministry would need to identify its lowest-performing, lowest-priority program spending for the purposes of reinvestment. Such a model would decentralize fiscal planning and help to control or limit program spending which will be critical to delivering on the government’s overall fiscal objectives.

2. Ensure the four conditions or ingredients for successful government transformations – namely, (1) clear metrics and benchmarks, (2) technology and project management capacity, (3) conservative saving estimates, and (4) cybersecurity risk mitigation

The Ontario government should be lauded for its Smart Initiatives. The process for improving government should be dynamic and ongoing. The scholarship, experiences from elsewhere, and our own experiences point to four key conditions or ingredients for success. We will not fully relitigate them here.

But these four conditions or ingredients (and their rationales described above) should be key as the Ontario government rolls out its Smart Initiatives. Perhaps the most under-appreciated may be the question of data breaches and cybersecurity risks. Making government better, smarter, and more efficient is a laudable goal. Protecting against data breaches and cyberattacks is increasingly a key consideration for such an agenda. Saving money at the expense of privacy is not a worthwhile trade-off.

It is important therefore that the Ontario internalize these different factors for success but, if there is one that is new and evolving, it is accounting for the risk of data breaches and cyberattacks in their analysis.

3. Leverage government decentralization to achieve efficiencies and support economic activity in rural and economically distressed parts of the province

Previous Ontario 360 papers have discussed the growing place-based bifurcation in the province. The government has similarly identified it as a major challenge. The question of regional economic disparity should animate all aspects of government policy. The Smart Initiatives is no different.

Placing an emphasize on decentralizing the government’s real property and employment footprint could achieve fiscal savings and support communities in need. The United Kingdom’s experience with such a “decentralization” agenda is worth exploring including how to determine which government functions should be decentralized to which regions. This cannot simply be a redistribution exercise. It must balance the government’s twin goals of improving pre-existing spending and better supporting rural and economically distressed places in the provinces. But notwithstanding these caveats, given the growing urban/rural divide across the province, the Ontario government should embark on an ambitious decentralization agenda in order realize efficiencies and boost economy activity in rural and economically distressed parts of the province.

Kevin McCarthy has over nineteen years of public policy and financial sector experience, helping implement policy at multiple levels of government and advising businesses on managing policy and political risk.

Kevin worked for over 10 years in government, serving as an advisor to the Ontario Premier, provincial and federal finance ministers. Serving as the Director of Policy and Chief of Staff to the federal Finance Minister over the course of eight years, Kevin was involved in all significant financial issues the government of Canada dealt with from 2006 to 2013, including the financial crisis of 2008-2009 and helping to implement eight federal budgets.

After leaving government, Kevin worked at Scotiabank in a number of roles including running their Government Affairs team, Investor Relations and Commercial Banking.

Kevin is now the Head, Corporations and Institutions at Enriched Academy, a company that provides financial education through online courses and live events and a Senior Advisor at Foresight.

Kevin has a BA (Hons.) in Political Studies and History from Queen’s University and received the Queen Elizabeth II Golden Jubilee Medal for his work in public policy related to the creation of the Tax-Free Savings Account.