Policy Papers

Opportunity Zones: An Opportunity for Ontario

Lorenzo Gonzalez and Sean Speer outline how economic growth and dynamism have not been evenly distributed across the province, especially when rural and urban areas are compared.

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

1) Pursue intergovernmental cooperation with the federal government on launching the Opportunity Zones model in Ontario or across the country.

2) Enact a “made-in-Ontario” place-based investment tax credit that draws on a combination of the Opportunity Zones model, the federal government’s Atlantic Investment Tax Credit, and Ontario’s 2002 Tax Incentives Zones Act.

3) Redesign the Northern Ontario Heritage Fund and the Rural Economic Development Fund to better target private investment in economically-distressed communities.

Introduction

Although Ontario has seen relatively stable employment growth in recent years, economic growth and dynamism have not been evenly distributed across the province, especially when rural and urban areas are compared. Ontario’s economy is geographically concentrated in its major urban centres, particularly in the Toronto and Ottawa regions, where economic output and net job gains far outpace the rest of the province.[1] As Weseem Ahmed’s paper for the Ontario 360 project shows, the Province of Ontario is home to significant regional economic disparity.

In light of structural economic changes and the knowledge economy’s tendency towards clustering and agglomeration, this trend of uneven growth and opportunity is likely only to continue. Policymakers are faced with a choice: redistribute the economic gains from some places to others or try to catalyse more market activity in undercapitalized economically-distressed places.

The Ontario government has signaled in its recent Fall Economic Statement that it intends to pursue the second option. It has stated that:

“Over the coming months, the government will be consulting on ways to encourage investment into rural and undercapitalized areas of the province with the goal of restoring Ontario’s competitiveness and allowing the private sector to create jobs and growth. The outcome could include exploring potential changes to the tax system that may benefit overlooked areas of the province and new, upcoming industries.[2]

This paper aims to contribute to a set of options available to the government by analysing the U.S. experience with a new place-based policy called “Opportunity Zones” and its potential lessons for Ontario.

What are Opportunity Zones?

The Opportunity Zones initiative is an innovative economic development program established in the United States by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.[3] Its purpose is to revitalize economically distressed communities across the country by using tax preferences to encourage long-term private investment in those undercapitalized communities. An estimated $6.1 trillion in unrealized capital gains held by American taxpayers[4] can potentially be leveraged to create economic activity in almost 9,000 areas across the United States designated as “qualified Opportunity Zones.”

Nearly 35 million Americans (roughly the same population as Canada) live in these designated Opportunity Zones, which have an average poverty rate of over 32 percent (compared with the national average of 17 percent).[5] The designation, including eligibility for the tax preferences, will last for 10 years. The goal is to help turn these neighbourhoods and communities around over the course of the decade.

Investments will come from “qualified Opportunity Funds,” which have been established since the 2017 law was passed enabling the pooling of capital and investment in qualified opportunity zones. Qualified Opportunity Funds can be organized as corporations or partnerships and must hold at least 90 percent of their assets in qualified opportunity zone property. Qualified opportunity zone property includes qualified opportunity zone stock, partnership interests, and business property. This paper elaborates on the details.

The Opportunity Zones initiative follows earlier place-based initiatives to catalyse and stimulate investment in undercapitalized and economically-distressed communities. Past efforts such as Empowerment Zones, Enterprise Communities, and the New Markets Tax Credit have produced mixed results.[6] The Opportunity Zone model has sought to learn from these initiatives. It is more neutral, flexible, and market-driven than these previous models.

The purpose of this paper, then, is to analyse the Opportunity Zones model program in the United States for an Ontario audience and derive some lessons and insights that may be relevant for Ontario policymakers. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: section 2 discusses the origins of the Opportunity Zones initiative; section 3 provides details about the program’s design and implementation; section 4 reviews the effects of the initiative to date; section 5 outlines the case for a greater emphasis on policy-based strategies in Ontario; and section 6 sets out recommendations for ways in which the Ontario government may seek to address regional economic disparity, including potential adoption of the Opportunity Zones model.

The Origins of Opportunity Zones

The concept of Opportunity Zones has a bipartisan genesis. It originated in a 2015 concept paper by Jared Bernstein, a progressive chief economist to former vice president Joe Biden, and Kevin Hassett, a conservative economist and now-former chairman of U.S. president Donald Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers.[7] At the time, both economists were serving as advisors to the Economic Innovation Group, a bipartisan policy advocacy group that studies entrepreneurship and innovative investment strategies.

Bernstein and Hassett’s paper, “Unlocking Private Capital to Facilitate Economic Growth in Distressed Areas,” argued that the post-recession economic recovery was not widely experienced across the United States.[8] Some regions had returned to pre-recession output and employment, while others had continued to struggle. Indicators such as the performance of the stock market disguised serious regional economic disparities.

The biggest beneficiaries of the economic recovery were, in fact, investors. The Dow Jones almost tripled from 2009 to 2014, rising nearly 12,000 points, and investors in the S&P 500 gained over $4 trillion in 2013 alone. As a result, U.S. investors held an estimated $2.3 trillion in unrealized capital gains in stocks and funds as of December 2015.

The bipartisan economists saw a possible link between the country’s regional economic disparity and this growing stock of unrealized capital gains. They argued that, if policymakers could induce investors to unlock their capital gains and direct the proceeds to economically-distressed communities, they could have a major impact on economic development. The question, though, was how to design a set of policy inducements that would avoid producing large distortions and would ultimately lead to better results than past experiments with place-based economic development.

Bernstein and Hassett proposed a new flexible, market-driven model that could harness the power of financial intermediaries such as private equity firms, banks, venture capitalists, and mutual funds, and in so doing minimize the risk of what is sometimes called “government failure.” This point is important: the goal was to design a model that would function like a venture capital firm and not like a bureaucratic agency.

In particular, they recommended a special-purpose vehicle that would specialize in investments in assets and businesses in designated communities. Through special tax provisions, the investment vehicle would be able to attract capital from a mix of individual and institutional investors for investment in numerous projects at any given time. The pooling of resources would mitigate risks and potentially move a high volume of investments into distressed communities at relatively low cost to the government.

These initial design considerations were important for attracting political support – particularly among conservatives who were suspicious of state-centred regional development strategies. Bernstein and Hassett emphasized that their proposal was different from past models, which had tended to involve a significant role for the government in selecting projects or were limited to capitalizing particular places or firms. This model would be driven by the private sector and would be broadly neutral, apart from the expectation that it would target economically-distressed places. The government’s only role would be to provide for an overall legal and financial framework.

It is also important to observe that Bernstein and Hassett’s proposal was designed to catalyse new investment rather than simply to reward investment decisions that would have occurred anyway. A tax credit for investments in distressed communities or a direct spending program to encourage business investment in such communities might have attracted some incremental investment, but it is also quite possible that such initiatives would mostly have subsidized pre-planned investment. The creation of a framework that involved establishing new special-purpose financing vehicles and the pooling of unrealized capital gains was designed to pull new, untapped dollars into designated locations. The question of “incrementality” is something that policymakers elsewhere – including Ontario – need to consider when designing policies to encourage investment in undercapitalized communities.

Bernstein and Hassett’s model found bipartisan support in Washington. The concept of Opportunity Zones was originally introduced in a bill before the 114th Congress in April 2016.[9] It had impressive support from both sides of the aisle, led in the Senate by Republican Tim Scott and Democrat Cory Booker, and in the House of Representatives by Republican Pat Tiberi and Democrat Ron Kind. It was subsequently reintroduced in the 115th Congress, where it received nearly 100 congressional co-sponsors and was ultimately included in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.[10]

How Opportunity Zones Work in the United States

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act set out the broad framework for Opportunity Zones. Three features are worth detailing here.

Design of Tax Preferences

Remember that the goal of the Opportunity Zones model is to pull a portion of unrealized capital gains into economically-distressed communities. The model relies on three separate yet related tax inducements.[11] Any corporation or individual with capital gains can qualify.

- Temporary deferral of taxes on previously earned capital gains. Existing assets with accumulated capital gains are eligible for investment in Opportunity Funds (described below). Those existing capital gains are not taxed until the end of 2026 or at such time as the asset is disposed of.

- Basis step-up of previously earned capital gains invested. For capital gains placed in Opportunity Funds for at least 5 years, investors’ basis on the original investment increases by 10 percent. If invested for at least 7 years, investors’ basis on the original investment increases by 15 percent.

- Permanent exclusion of taxable income on new gains. For investments held for at least 10 years, investors pay no taxes on any capital gains produced through their investment in Opportunity Funds (the investment vehicle that invests in Opportunity Zones).

The underlying assumption in the United States is that some portion of the unrealized capital gains is subject to the “lock-in” effect, whereby investors are deterred by high rates of taxation from reallocating their capital to other assets.[12] This mix of inducements could therefore counteract the “lock-in” effect and encourage the deployment of the unlocked capital into designated Opportunity Zones.

Designation of Qualified Opportunity Zones

The U.S. law provides definitions and processes for designating both low-income community census tracts and exempt census tracts as Qualified Opportunity Zones.[13] It also specifies the time periods required to nominate and designate qualified opportunity zones. Once tracts are designated as qualified Opportunity Zones, their designation will last for 10 years, expiring on December 31, 2028.

The nomination process for qualified Opportunity Zones consists of two parts: the determination period and the consideration period.[14] Decisions for designating Opportunity Zones were pushed down to the state level. During the determination period, governors from all 50 states and U.S. territories, plus the mayor of Washington DC, were given a deadline, unless a 30-day extension was requested, to nominate low-income community census tracts for designation. If nominations were not received during the allotted time period, states and territories would have effectively opted out of the program. During the consideration period, the Treasury Department had 30 days, beginning on the date a nomination was received, to certify the nomination and designate eligible tracts as qualified opportunity zones.

Each state and territory was allowed to designate up to 25 percent of its low-income community census tracts as qualified Opportunity Zones. A census tract typically has a population of 2,500 to 8,000 people. States with fewer than 100 tracts could designate up to 25 tracts. To be considered a low-income community, a tract needed to have a poverty rate of at least 20 percent or a median family income of less than 80 percent of the median income of the area. This is the same definition as is used to determine low-income communities under other federal programs such as the New Markets Tax Credit program.[15]

Certain census tracts could be designated as qualified Opportunity Zones despite not meeting the low-income criteria. Up to 5 percent of non-low-income census tracts in each jurisdiction could be designated under an exemption. Exempt census tracts had to be contiguous with low-income census tracts that are designated as qualified Oopportunity Zones, and the median family income of the exempt tract could not exceed 125 percent of the median family income of a designated low-income census tract with which it is contiguous.

To facilitate nominations, the Treasury Department provided states with various guidelines and tools, including federal data that used the 2011-2015 American Community Survey data from the U.S. Census Bureau to identify eligible census tracts.[16] That tool identified over 41,000 population census tracts that were eligible for designation, which included 31,680 low-income tracts, and 9,453 non-low-income contiguous tracts.

The nomination and designation of qualified Opportunity Zones were done in several rounds. The first set of qualified Opportunity Zones were designated in April 2018, covering 15 states and three U.S. territories that met the first nomination deadline.[17] In May 2018 an update followed, which included designations in 46 states, five U.S. territories and the District of Columbia.[18] And in June 2018, the Treasury Department announced that it had completed final designations, to a total of 8,761 designated opportunity zones.[19]

Following what was believed to be the final round of designations, however, the Treasury Department in June 2019 reviewed the 2012-2016 ACS data and identified two additional eligible low-income community census tracts in Puerto Rico.[20] This addition was based on the enactment of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, which allowed a special rule for Puerto Rico that deems every low-income community census tract in Puerto Rico to be a qualified Opportunity Zone. As a result, there are now 8,764 qualified opportunity zones, covering parts of all 50 states, five U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia. All current qualified Opportunity Zones will remain so designated until December 31, 2028.

The rationale for allowing state governments such a short timeframe for determination was to minimize the role of lobbying and politics in the designation of Opportunity Zones. A long, drawn-out process would risk giving communities and businesses time to launch active campaigns for designation.

Decentralization was also highly important. It is worth observing, for instance, that U.S. states chose different strategies for designating Opportunity Zones. Some limited their designations to the poorest-performing parts of their states. Others sought to spread their designation across each county in their state.

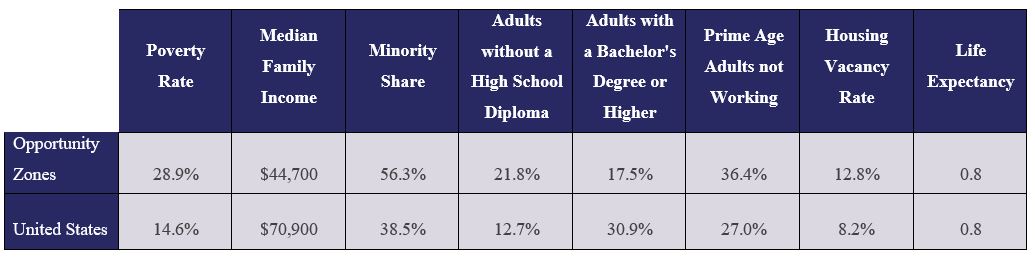

In hindsight, while the designation process was generally rooted in empirical metrics and minimized the role of politicization, it was not without its challenges. Recent news that, as a result of pressure from the Treasury Secretary, the Treasury Department approved an Opportunity Zone in Nevada that did not meet the criteria is obviously a concern.[21] Still, a 2018 study by the Urban Institute verified that the designated zones do have lower incomes, higher poverty rates, and higher unemployment rates than eligible non-designated tracts.[22] Overall, the economic performance of the designated Opportunity Zones lags far behind the national average (see Table).

TABLE: ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE OPPORTUNITY ZONES COMPARED TO THE UNITED STATES

Source: Economic Innovation Group

Qualified Opportunity Funds[23]

As alluded to above, the tax preferences are available only to capital gains invested in qualified Opportunity Funds. These funds are investment vehicles that must hold at least 90 percent of their assets in qualified Opportunity Zone assets. Qualified Opportunity Zone assets include qualified Opportunity Zone stock, qualified Opportunity Zone partnership interests, and qualified Opportunity Zone business property. A qualified Opportunity Fund cannot invest in another qualified Opportunity Fund.

The law also outlines the process for establishing an Opportunity Fund. Any taxpayer that is a corporation or a partnership for tax purposes can self-certify as a qualified Opportunity Fund by filing as a qualified Opportunity Fund with their federal income tax return.[24] Limited liability companies also qualify to become Opportunity Funds, as long as they choose for federal tax purposes to be treated as either a partnership or a corporation.[25]

The tax form is used by Opportunity Funds both for initial self-certification and for annual reporting of compliance with the 90 percent asset test.[26] The 90 percent investment standard is determined by averaging the percentage of Opportunity Zone assets held in a qualified opportunity fund on the last day of the first six-month period of the tax year and the last day of the tax year. If an Opportunity Fund fails to satisfy the 90 percent asset test, it may have to pay a penalty for each month it does not satisfy the investment standard.

It is difficult to confirm the official number of existing Opportunity Funds since government officials did not make tracking mandatory. This has been a general problem. In hindsight, the Opportunity Zones model lacks an evaluation regime to determine its effectiveness. Congress is apparently exploring possible solutions, among which is the requirement that the Treasury Department collect data and report to Congress on investments held by Opportunity Funds.[27]

One estimate puts the number of Opportunity Funds at nearly 290, representing $64.85 billion in investment.[28] A more conservative estimate puts the number of Opportunity Funds at 183, totalling $44 billion in investment.[29]

What is interesting, however, is the focus and design of the Opportunity Funds. Some have regional mandates – that is, they are focused on investing in a particular city or state. Others focus on particular asset classes. And another set have “social impact” mandates, so their focus is not only targeting investment returns. This is one of the virtues of the Opportunity Zone model. It does not require any role for central coordination or planning. The incentives embedded in the model are producing a response from the market. Investors, money managers, and charitable foundations are experimenting with different models for pooling capital and structuring investments.

Most Opportunity Funds thus far have focused primarily on commercial real estate. This was somewhat predictable, as real estate projects were the most “shovel ready.” They are also the most straightforward for the purposes of the model. Other asset classes such as venture capital are more complex under the time limitations of the Opportunity Zones model. The Treasury Department’s initial regulatory guidance was therefore focused on real estate and as a result that is where most of the investment has been deployed.

While the original legislation provided an overview of the tax benefits offered to investors in qualified Opportunity Funds, the statutory language contained little practical guidance, causing uncertainty about how taxpayers might meet the investment requirements for the program.[30] In October 2018, with the release of the first proposed regulations, the Treasury Department provided guidance for moving forward with real estate deals, but the details regarding other asset classes are still moving slowly. Just last month, for instance, the Treasury Department indicated that marijuana-related investments will not be eligible.[31] Ongoing uncertainty about the treatment of different asset classes has hindered the development of the Opportunity Zone model. The lack of regulatory clarity is widely seen as the main issue.[32]

The treatment of venture capital is a clear example. Business incubation has different dynamics and timelines than real estate investment. The purpose is to provide short-term capital and then divest as firms mature and start the process over again. But this type of investing has been a small part of Opportunity Funds’ portfolio thus far because the Treasury Department has not prescribed how the rules – including the application of the tax preferences – will work for businesses. This is an important takeaway for policymakers in Ontario and elsewhere. The Opportunity Zones model may look relatively straightforward but it entails design complexities that can be difficult for the government to anticipate or respond to. The result can be policy uncertainty that lowers investor confidence and undermines program effectiveness. Design considerations are key. Simplicity and clarity are fundamental for a policy intervention to be successful.

Reviewing the Impact of Opportunity Zones

The main question is: are Opportunity Zones working as intended?

Remember, the target for the U.S. initiative is the $6.1 trillion available in unrealized capital gains.[33] The goal is to unlock a portion of this capital and have it deployed to undercapitalized communities across the country. U.S. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin has speculated about the Opportunity Zones initiative bringing $100 billion to economically distressed communities.[34]

As described above, it may be the case that the Opportunity Zones initiative ultimately hits his target. Different estimates put the current level of capital within Opportunity Funds between $44 billion[35] and $64 billion.[36] But the level of capital invested is clearly not the right metric for determining success. The real measure is whether it helps to catalyse economic activity in economically-distressed communities.

It is too early to judge the initiative’s overall effectiveness. It is not set to expire until 2028, and the previous section has highlighted some of the delays associated with regulatory uncertainty. Still a combination of qualitative and quantitative evidence to date is available.

One study that examined real estate investment under the Opportunity Zones model found evidence that it is associated with an increase in the price of depreciated property and vacant land within zones but is not producing broader-based increases in property values. As the authors observe:

If the tax benefit would spur the local economy, one would expect price increases for all properties, not just the ones getting the actual tax benefit. Instead, we find that only properties that benefit from the tax break – redevelopment properties and vacant land – see their prices increase. The tax break is essentially factored into the land price.[37]

The study’s findings are preliminary, but they do raise questions about whether the model will have a broader effect on the targeted communities or merely produce windfalls for investors.

Other analyses also raise concerns about the effectiveness of Opportunity Zones. One concern is that the model is creating distortions whereby capital is flowing to Opportunity Zones to the detriment of other in-need communities or more efficient allocations. Remember that, whereas 31,000 possible Opportunity Zones were nominated on the basis of their economic conditions, only about 8,700 were ultimately selected. That means that more than 22,000 economically-distressed communities and contiguous areas are not currently benefiting from the model.[38] This is a legitimate criticism. But it is also a function of any government policy that is not broad-based and neutral.

New research paints a more positive picture, however. A recent report by a Washington-based think tank called the Economic Innovation Group highlights new experimentation by Opportunity Funds on business start-ups. As the group’s president recently said in his testimony to Congress:

Even though the marketplace is far from fully formed, the Opportunity Zones incentive is being used to support a wide range of investments across the country just as Congress intended. Investments in clean energy, broadband infrastructure, vertical farming, manufacturing, and industrial facilities are a sign of the long-term potential of the incentive, even if the scale of capital flowing to such investments remains limited. Many early investments are going into basic neighborhood amenities, such as grocery stores in food deserts, medical clinics, and new housing of all different types. Small cities are using Opportunity Zones as a catalyst to build or expand local innovation districts or revitalize blighted downtown corridors. Anchor employers, from Fortune 500 companies to major hospital systems, are helping to jumpstart investment in communities like Cleveland, OH, and Erie, PA.[39]

This progress is important in light of the concentration of business formation in large metropolitan areas. Just consider that, from 2010 to 2014, five cities produced as many new businesses as the rest of the country.[40] The only way to counteract this type of entrepreneurial concentration is to spread new capital more broadly across the country. It seems clear that broader distribution will require more than a reliance on the market’s efficient allocation. Some form of policy intervention will be needed.

The bet here is that the Opportunity Zones model is the least intrusive and distortionary form of intervention to achieve this goal of inclusion growth. Ultimately, even the strongest proponents of Opportunity Zones recognize the risks – including the possibility of distortions. Policymakers are taking precautions to minimize distortions but it is impossible to eliminate them. The judgement that needs to be made is whether the overall goal is worth the risk of distortions. As a former Obama official who has been a champion of the Opportunity Zones model puts it: “The status quo is far worse than what is a massive policy experiment in providing an incentive for investment.”[41]

The Case for a Place-Based Strategy

Although it is too early to determine whether the Opportunity Zones program will be successful in the United States, it is evident that the program has been able to harvest billions of dollars in unrealized capital gains for economic development purposes. More important, the program has brought new energy, ideas, and much-needed attention to economically-distressed areas, all of which are needed in parts of Ontario. One of the major economic development issues in Ontario is uneven growth across regions. If left unaddressed, further regional imbalances can be expected.

Given that the current economic, political, and social landscape is increasingly rooted in the economics of geography, the question becomes whether regional imbalances can be addressed. Two considerations come to mind.

The first is that people’s frustration should be acknowledged – ignoring it will only amplify distress and resentment among communities with the greatest need. The federal government’s $950 million superclusters initiative,[42] for example, targeted only the most prosperous regions in Canada in pursuit of further economic growth, thereby continuing the lack of attention to and support for economically-distressed communities.

The second is rather than expect people to leave lagging or declining regions for places where opportunities are more abundant, governments need to renew efforts to make opportunities available to people regardless of where they choose to settle. Many place-based economic development policies have attempted to do this for decades to no avail, but these policies can provide lessons for improving and remodeling existing approaches. This is exactly what the United States is attempting with the Opportunity Zones model. It represents the application of the insights from the cumulative failures of past place-based policies.

The program makes three evident improvements over earlier place-based policies such as “Enterprise Zones.” First, unlike many other place-based programs that target individual firms or industries, the Opportunity Zones program uses a special-purpose vehicle, somewhat like a venture capital firm, to make investments in designated areas. Second, since it imposes few investment constraints, the initiative is both market-driven and has scale. The third, and perhaps the most important improvement is that the program encourages the pooling of resources of multiple individuals and institutional investors, mitigating the risk to any one person or firm and thus changing the risk profile of distressed areas.

These features are key for Ontario policymakers to consider as they grapple with regional economic disparity and questions about the most appropriate policy interventions to help catalyse economic activity in distressed communities.

Recommendations for Ontario

Thus far, the paper has examined the Opportunity Zones model, including its design and implementation, in order to derive possible lessons for the Province of Ontario, which is facing its own challenges of regional economic disparity. Weseem Ahmed’s paper highlights Ontario’s challenges with agglomeration, particularly with respect to capital flows and business formation.

The Ontario government has signaled an intention to adopt policies that can push the market to produce broader-based economic activity. This final section of our paper considers the lessons of the Opportunity Zones model for the province in order to help the government in its consideration of policy options.

We would highlight three possible options for the Ontario government.

1) Intergovernmental Cooperation on Opportunity Zones

Ontario’s tax treatment of capital gains is a function of the federal treatment of capital gains due to the intergovernmental integration of tax administration. Lowering or deferring the provincial capital gains tax in order to induce capital investment to economically-distressed parts of the province would be challenging without federal participation.

A recent Fraser Institute paper that recommended that Alberta reform its treatment of capital taxes could be instructive for Ontario. The authors suggest that if a province wishes to eliminate or waive capital gains taxes from personal taxes, it could do so by excluding capital gains from provincial income taxes through a clarification or amendment of its tax collection agreement with the federal government.[43] This may be possible, but it would ostensibly require federal cooperation and risks causing confusion for investors. It would also blunt the incentives if investors were still subject to federal taxes on capital gains.

A more productive option would be to work with the federal government to establish a joint federal-provincial Opportunity Zones model in the Province of Ontario or as a fully national initiative across Canada. That the Trudeau government has appointed a Minister for Rural Economic Development for the first time suggests that the federal government may be open to such a joint initiative. The Ontario government should therefore approach the federal government about partnering on it.

Given that the federal and provincial governments are both running budgetary deficits, it is worth emphasizing that adopting an Opportunity Zones model would have minimal fiscal implications. Remember that the model involves unlocking unrealized capital gains that are in any case not subject to taxation until they are realized. It would therefore represent a low-cost, potentially high-impact policy experiment for both governments.

If the Ontario government were to pursue this path, it should keep in mind some key lessons derived from the U.S. experience. Let us highlight three. The first is to ensure that when the initiative is launched the legislation and accompanying regulations are as clear and ready to be enacted as possible. The second is that the selection of designated zones must be decentralized and transparent. The third is that clear evaluation metrics to determine the initiative’s overall effectiveness need to be put in place.

Given that we are not able to make a determination about the effectiveness of the Opportunity Zones model, it would make sense to set a ten-year timeframe similar to the U.S. initiative in order to enable a medium-term assessment. At that point, if it was seen to be working, the government could ostensibly change the mix of designated Opportunity Zones.

2) Provincial Place-Based Investment Tax Credit

If the Ontario government wished to pursue a tax-based strategy to incentivize investment in economically-distressed parts of the province but did not wish to target capital gains or could not get Ottawa to participate, other policy options are worth considering.

The province could implement a tax credit to encourage investments in various types of assets – such as buildings, business formation, machinery and equipment, and clean energy – in economically-distressed parts of the province. The criteria for asset classes and the threshold for a community or neighbourhood’s eligibility according to different economic metrics could follow parts of the Opportunity Zones model.

The concept of regionalized tax incentives is not unprecedented. The federal government’s Atlantic Investment Tax Credit currently offers a 10 percent tax credit for qualifying acquisitions of new buildings, machinery and equipment, and prescribed energy and conservation property used primarily in qualified activities in the Atlantic provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula, and their associated offshore regions. Qualified activities include farming, fishing, logging, manufacturing and processing, grain storage, peat harvesting, and the production or processing of electrical energy or steam. Roughly 5,000 individuals and 5,700 corporations claim the credit each year at a cost of roughly $230 million annually.[44]

Ontario could similarly extend a placed-based investment tax credit to investments in underperforming parts of the province. The generosity of the credit is scalable. It could match the federal credit of 10 percent, or the government might set it at 11.5 percent, which is the current provincial corporate tax rate. But in order to provide the level of inducement represented in the tax preferences that comprise the Opportunity Zones model, it may need to go higher.

A placed-based investment tax credit would otherwise be straightforward to implement and ostensibly help to catalyse some degree of new investment and economic output in underperforming places. In order to test its effectiveness, the government could experiment with it on a sunsetting basis for five or ten years.

The downside of this approach is that it would be difficult to determine incrementality. It is highly likely that the government would end up subsidizing investments that would have occurred anyway. It may also not produce the energy, ideas, and attention that a bolder proposal involving new, special-purpose vehicles has seemed to achieve in the United States.

A more ambitious option would to be revisit an Ontario-based precedent. The case dates back to 2002, when the then-Progressive Conservative government passed the Tax Incentive Zones Act.[45] That legislation allowed for the designation of tax-incentive zones in which eligible new businesses could qualify for the reduction or cancellation of certain provincial taxes, fees, and charges. In addition, with the prior approval of the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing, municipalities could pass by-laws reducing or cancelling municipal taxes, and reducing or cancelling fees and charges payable to them.

According to the province, the 2002 policy was a response to popular demand by municipalities requesting the ability to provide tax incentives to business owners in order to encourage new construction and new business development. This was at a time when many jurisdictions, including the United States, were running various “enterprise zones” programs to spur economic development through tax incentives.

The rollout of Ontario’s tax-incentive zones program started with a competition soliciting municipalities to come forward by October 18, 2002 with Expressions of Interest to host one of six pilot tax-incentive zones. In the end, 62 expressions of interest were received and in May 2003, the government declared Northern Ontario as the first tax-incentive zone, with additional pilot tax-incentive zones in southern Ontario pending.[46] The designation was to last ten years, effective January 1, 2004.

The program was never implemented, however. Following the 2003 provincial election, the subsequent government ultimately canceled the program. The current government could re-establish the Tax Incentive Zones framework, taking into account the lessons and insights of the Opportunity Zones model.

3) Redesign the Northern Ontario Heritage Fund Corporation Programs and the Rural Economic Development Fund

The Ontario government supports business development in Northern and rural communities through the Northern Ontario Heritage Fund and the Rural Economic Development Fund. The two programs provide a mix of community grants, forgivable loans, and loan guarantees to encourage and support economic development in underperforming communities. The annual budget of the Northern Ontario Heritage Fund is roughly $100 million. Funding for the latter has been rolled into the Jobs and Prosperity Fund, which has a budget of approximately $270 million per year.

If the government did not want to pursue a tax-based approach, it could consolidate, redesign, and possibly augment the Northern Ontario Heritage Fund and the Rural Economic Development Fund to create a new direct-spending initiative to encourage and support private investment in economically-distressed communities. The program could target asset classes and set the threshold for a community or neighbourhood’s eligibility according to different economic metrics based on the Opportunity Zones model.

The program could have a per-project funding cap (similar to a tax preference) and focus on projects that have the greatest potential to catalyse economic activity in economically distressed communities. There could be scope for an independent panel to evaluate the proposals in order to minimize the risks of politics in project selection.

The downsides of this model in relation to market-driven models are that the government would select the applicants and there is a similar risk of failing to achieve incrementality. Most fundamentally, though, it would be a less flexible and more distortionary model, given the role of scarcity and need for government to decide which projects should proceed.

This is, according to the policy analysis on past failures of place-based policies, the option least likely to produce positive outcomes. But there may be design innovations such as making use of prizes (funding awarded to proposals that address a challenging regional or local problem) or setting high thresholds for matching private investment. The point is that, although there is room for policy innovation and the risks may be worth it, our research suggests that this may not be the most effective option.

Conclusion

As the Ontario government considers how best to address regional economic disparity in the province, this paper has sought to contribute to its thinking by analysing the Opportunity Zones model in the United States.

Given that Opportunity Zones model is still in its nascent stages in the United States, it is difficult to determine whether it will be successful in the long term. Nevertheless, it is evident that the initiative has brought new energy, ideas, and much-needed attention to solving problems facing economically distressed communities. To date, Opportunity Zones have harvested billions of dollars in unrealized capital gains for economic development purposes, which in itself should be considered a success.

Opportunity Zones have the potential to play a role in addressing regional economic disparities across Ontario. Of course, much consideration is needed in regard to how such a program would be designed and implemented to be effective in Ontario’s economic, political, social, and legal context.

If Opportunity Zones are well executed and integrated with existing and new economic development policies, then lagging and declining regions in Ontario may not only receive the economic stimulus they need, but get the attention they deserve.

Author Bio

Lorenzo Gonzalez is an economic developer at Digital Main Street, a Toronto-based, not-for-profit organization that helps small business owners in Ontario adopt digital technologies to improve and modernize their businesses. Lorenzo has a Masters in Economic Development and Innovation from the University of Waterloo. He has written about Opportunity Zones in the Globe and Mail.