Policy Papers

ON360 Transition Briefings 2022 – Turning Aces Into Assets: The Case For Gambling Reform In Ontario

Ontario has just become the first province to open its legal gambling market to private internet gaming providers. But as with all forms of gambling, this development has a dark side. Is the provincial government itself addicted to gambling money?

Issue

Ontario has just become the first province to open its legal gambling market to private internet gaming providers. As of April 4, 2022, Ontarians can play casino-style games online and place bets on sports, including single games, through sites regulated by iGaming Ontario. According to the provincial regulator, the launch of iGaming marks the triumph “of a legal internet gaming market” over “its previous grey market standing.” But as with all forms of gambling, this development has a dark side. It was only a matter of time before Ontario expanded its gambling market—not because of popular demand, but because the provincial government is addicted to gambling money and is eager to seize any opportunity to get more of it, regardless of the costs to the people it is supposed to protect.

Background

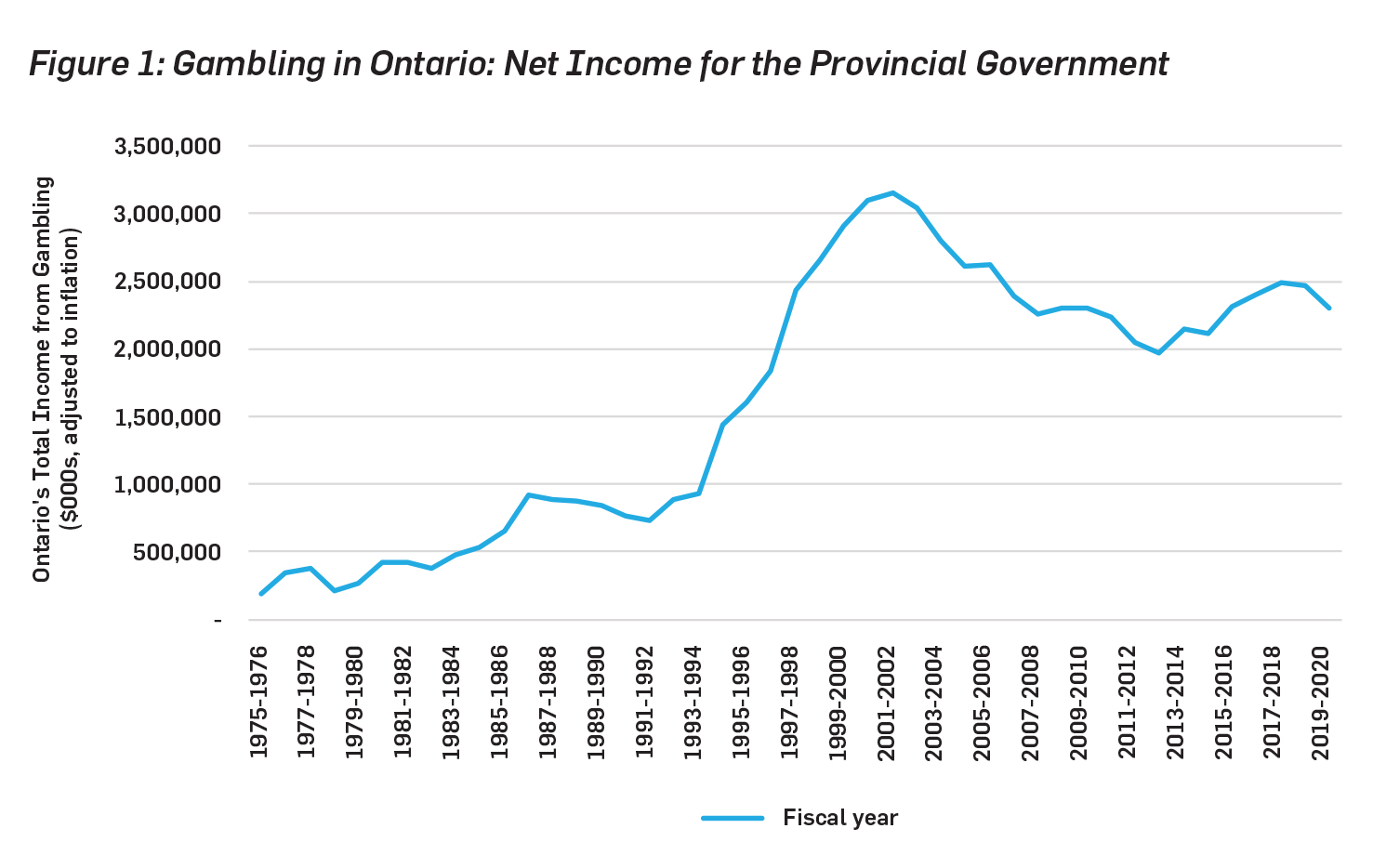

One of the classic dynamics of addiction is the law of diminishing returns: as time goes on and the addict’s tolerance builds, the same hit no longer offers the same reward, forcing the addict to seek out more and/or different sources to satisfy their craving. Ontario is no exception. When gambling was first legalized in the 1960s, the only government-run gambling format available was ticket lotteries, and the relatively modest proceeds were invested into forms of public entertainment. This “games for games” approach didn’t last long, however. Despite the government’s strenuous insistence that allowing provinces to run lotteries would “not promote the expansion of gambling,” the income of the Ontario Lottery Corporation (OLG’s predecessor) nearly tripled in its first ten years of operation. As lottery profits grew, so too did the list of their legally-sanctioned uses—until lottery funds were in all but name being dumped “into the big, black hole of the bottomless pit of the consolidated revenue fund,” as one Ontario MPP memorably noted in 1990.

By the late 1980s, lottery profits had started to decline, falling by nearly 20% between 1987 and 1992. But Ontario was hooked. Seeking to keep the cash pipeline flowing, the provincial government legalized casino gambling, opening its first casino in Windsor in 1994. By 2000, Ontario had merged casino and lottery operations into what is today known as OLG. It also dropped the official requirement that gambling revenue be limited to certain uses: OLG profits would be piped directly into the consolidated revenue fund. For a while, the changes worked. Gambling revenue skyrocketed, boosted primarily by massive profits from the casinos’ shiny new slot machines. Adjusting for inflation, in 2002 the Ontario government made nearly $3 billion from gambling—approaching four percent of the province’s total revenue.

But sure enough, the novelty of casinos eventually started to wear off as well. By 2012, OLG’s annual contribution to the provincial government’s consolidated revenue fund had fallen by over $1 billion. This time, Ontario turned to a “modernization plan” for the struggling OLG—implementing, as one commentator observed, “what is somewhat euphemistically described as a ‘more market-driven and consumer-responsive strategy’” to “try to milk every single dollar there is to be spent” on gambling. Unsurprisingly, even with OLG’s expansion of lottery-ticket sales, its privatization of casinos, and its new laser focus on profit, growth was relatively small and short-lived. Revenue plummeted in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet profits were already starting to plateau by 2017—without having made up even half of the billion-dollar decline from their 2002 peak. Thus Ontario’s turn to single-game sports betting and iGaming this spring: right on schedule as the roughly ten-year gambling cycle enters another period of decline.

New Risks with iGaming

And so the story goes: the province, facing a cash withdrawal, moves into a new gambling market, which captures Ontarians’ attention (and, more importantly, wallets) for a decade or so—until their interest starts to wear off, OLG revenues shrink, and the cycle begins anew. Each new expansion comes wrapped in consumer-focused language: iGaming in Ontario is designed to “give consumers enhanced entertainment choice, support the growth of a new, legal market and generate revenue that can help fund programs and services that benefit all of us,” according to its new director.

Yet the government is not just meeting existing demand safely but creating demand, trying to eke more cash out of the population without having to go through the arduous and unpopular process of raising taxes. One need look no further than OLG’s hefty marketing budget: between 2000 and 2020, OLG spent an average of $313 million every year encouraging Ontarians to gamble more.

The real problem with government-run gambling in Ontario, however, is not that these efforts to boost gambling revenue have consistently failed to pay off in the long term. It is that the province’s relentless pursuit of profit has come at the expense of its population’s welfare. Unsurprisingly, the greatest harms are borne by the most vulnerable: low-income families and problem gamblers.

Ontario’s gambling system disproportionately burdens the poor. Since 2000, Ontario has treated its gambling profits just like tax revenues: they are deposited into the consolidated revenue fund and spent on the same budget priorities. As a tax, however, gambling is regressive, taking more from the poor than from the rich relative to income.

In the bottom income quintile—that is, the lowest-earning fifth of Ontario’s families—the average household spends almost five percent of its after-tax income on gambling each year, which is nearly three times what the highest quintile spends. (It is also well above the threshold for lower-risk gambling set by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, which recommends spending no more than one percent of annual household income on gambling.) Our progressive income and sales taxes, in contrast, are designed to ensure that those with higher incomes shoulder a heavier tax burden. Households in Ontario’s highest-earning quintile turn over 23 percent of their incomes to income tax, a rate nearly ten times higher than the 2.5 percent collected from the poorest quintile; low- to moderate-income taxpayers also receive regular rebates

from the government so they will not be disproportionately affected by sales taxes.

Nor can these profits be dismissed as a “voluntary” tax. Modern gambling formats are engineered—quite successfully—to manipulate players into spending past their voluntary limit. More than half of OLG’s profits come from electronic gambling machines, which are designed to override players’ self-control of their playtime and spending with features that make them think they’re closer to winning, or are winning more often, than they actually are.

The injustice of the “voluntary” label is felt most acutely by those who bear the greatest costs of Ontario’s gambling system: those who struggle with a gambling addiction and the friends, family members, and communities who struggle with them. Problem gamblers make up less than two percent of Ontario’s population, but are responsible for up to 24 percent of gambling expenditures. If nearly a quarter of Ontario’s gambling revenue comes from people who are by definition no longer in control of their gambling, it is clear that the term “voluntary tax” is at best misleading.

Problem gamblers are also most at risk from the recent expansion of gambling in Ontario. Indeed, the leadup to iGaming’s arrival saw experts and recovering problem gamblers expressing deep concerns about the potential for the new gambling opportunities to trap players in addiction. Their concerns are hardly unwarranted. Recent research has found that sports bettors are at a higher risk of problem gambling and gambling harm than non–sports bettors. Online gambling makes gambling dangerously easy to access—players can place bets anytime, anywhere. It also tends to involve riskier forms of gambling: fast-paced games with frequent betting, quick access to multiple types of games, consumption of alcohol while gambling, and relatively easy access to more money if and when players start to lose.

Ontario’s gambling industry is a predatory system that siphons wealth from its most vulnerable citizens’ bank accounts. The province only makes money from casinos, lotteries, and now iGaming and sports betting because gamblers—including those experiencing poverty and/or addiction—come out poorer in the long run. Yet gambling is hardly an efficient way to collect revenue. For every dollar that leaves a gambler’s pocket, only 38 cents ends up in government coffers. The rest of OLG’s revenue goes to prizes—money taken from the many to be concentrated in the hands of the very, very few—and to operating expenses.

With iGaming and single-game sports betting added to the market, the government’s take will be an even lower proportion of gamblers’ spending. Indeed, private casino operators have expressed concerns that iGaming will cannibalize revenue from land-based casinos, which would mean less revenue both for the province—which collects a lower share of revenue from iGaming than it does from casinos—and for the host municipalities that collect fees from casinos within their jurisdiction.

Chasing new sources of gambling revenue for the provincial treasury may seem like an easy way for governments to get a quick infusion of cash, but is not a sustainable source of revenue in the long term. Defenders of the gambling industry describe it as an economic investment that creates jobs, but research has found that gambling’s overall impact on local economies is mixed at best. While destination gambling (gambling used mainly by tourists, such as in Las Vegas or Atlantic City) can benefit nearby hospitality-related businesses or real estate, the impact of convenience gambling (gambling used mainly by locals) is mostly harmful to local economies. Most Ontario casinos extract virtually all of their revenue from local populations—often at the expense of other local businesses—rather than bringing in new money through tourism. Even casinos located near the United States border draw most of their revenue from locals: Caesar’s Windsor and the two Niagara casinos, Ontario’s largest border venues, collect only 35 percent and 3 percent of their revenue, respectively, from American patrons.

Research suggests that Ontario is fighting a losing battle trying to keep locals entertained. Across the country, Canadians have been losing interest in gambling: the share of adults who engaged in any form of gambling throughout the year has declined from nearly four-fifths (77.2 percent) in 2002 to around two-thirds (66.2 percent) in 2018. Concerningly, average gambling spending by all Canadian adults—gamblers and non-gamblers alike—has remained stable over the same period, which means those who do gamble have been spending more.

Recommendations

It is past time for the government to admit it has a problem, but how can Ontario help the people who have been harmed? In our report Turning Aces into Assets, we review four policy options that would help reform Ontario’s gambling system so that it works for, not against, vulnerable families.

The first step is moving gambling revenue out of the consolidated fund: no government should use money collected disproportionately from the poor and addicted to pay for general spending.

1. Return annual gambling profits to the poor through cash transfers

A separate fund of gambling profits could be used to help the victims of Ontario’s gambling scheme in several ways. One of the simplest options would be to give the money directly back to the poor through cash transfers. Instead of subsidizing general spending with a regressive tax taken from the pockets of the poor, the group disproportionately providing the tax would be the group that benefits from the tax. This policy would in many respects be no different from existing sales-tax rebate programs like the GST/HST tax credit. Each year, the province’s total gambling profits would be divided among all adults or households below a certain income cut-off; the government could send a cheque to each recipient, deposit

the money in a TFSA, or distribute the money through the tax system as a refundable credit.

2. Promote asset building through a matched savings program

An even better option would be using this fund to help the poor build savings. Even a small emergency savings cushion has huge benefits for those who struggle to make ends meet: households with $500 or less in liquid savings in their bank accounts are 2.6 times more likely to use payday loans than households with $2,000 to $8,000 in the bank. However, government-incentivized savings programs, such as RRSPs and TFSAs, overwhelmingly benefit families who are already financially comfortable. Gambling profits could be used to reward saving by matching low-income households’ contributions to designated savings accounts. This could involve a simple top-up following the RESP model. Alternatively, in a more ambitious program, participants could receive, say, $3 in matching credits for every $1 they saved over a year, up to a total of $4,000 ($1,000 deposited by participants plus $3,000 in matching credits available at cash-out at the end of the year).

3. Work with financial institutions to offer prize-linked savings products

Another option would be using gambling profits to fund a prize-linked savings (PLS) program. Savers would buy lottery bonds from the government or deposit their money in a PLS account at a financial institution. The money that would normally be contributed to each participating savings account (or earned on each bond) as fixed interest would be pooled into a single prize fund; instead of earning regular interest, every participating saver has a chance to win. PLS products are popular in other jurisdictions—almost a third of the United Kingdom’s population has money invested in Premium Bonds, for example—and are particularly appealing to low-income savers and lottery players.

4. Use the OLG’s marketing budget to increase funding for problem-gambling research, prevention, and treatment

Finally, to help gamblers struggling with addiction, Ontario should reduce advertising spending and put the money towards problem-gambling research, prevention, and treatment. For gambling run by OLG, this would be a straightforward matter of slashing OLG’s marketing budget. In 2018 (the last year in which this information was published), OLG spent $282 million on marketing and promotion but only $64 million on problem-gambling prevention and treatment: $45 million was directed to the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, as per a policy that earmarks two percent of gross slot-machine revenue for problem gambling, and $19 million was devoted to its own Responsible Gambling program. In other words, OLG has been spending four and half times as much encouraging people to gamble more as it has fighting gambling addiction. These figures should at the very least be balanced, if not reversed. For private operators regulated by iGaming Ontario, the government could consider a policy requiring that online gambling and sports betting providers contribute a certain amount to the Ministry of Health for every dollar spent on advertising in Ontario. Ideally, the ratio would be one-to-one: not only would this improve problem-gambling treatment resources, it would also double the cost of marketing, a valuable check on the aggressive promotion of gambling in Ontario.

Conclusion

With public balance sheets upended by two years of intermittent lockdowns, the provincial government has a valuable opportunity for reform. It’s time to restructure Ontario’s gambling system to empower those on the economic margins, rather than preying on them. When Ontario is free from its addiction to gambling money, it will also be free to pursue more productive economic opportunities—a winning bet indeed.

Brian Dijkema is the Vice President of External Affairs with Cardus, and an editor of Comment.

Johanna Lewis is a former Researcher at Cardus. She is a graduate of Redeemer University, holding a Bachelor of Arts in Honours International Relations, and the Laurentian Leadership Centre.