Policy Papers

ON360 Transition Briefings 2022 – Investing in Housing First: an evidence-based intervention to end chronic homelessness in Ontario

Homelessness is the other end of Ontario’s housing crisis. Chronic homelessness results in substantial societal costs and puts pressure on multiple provincially funded services, including the health, justice, and social service sectors Drs. Ecker and Hwang propose policy changes that will provide immediate benefits by dramatically reducing chronic homelessness in communities across Ontario.

Issue

The number of people experiencing homelessness in Ontario continues to rise.[1] Chronic homelessness results in substantial societal costs and puts pressure on multiple provincially funded services, including the health, justice, and social service sectors.[2] Current approaches simply manage the problem of chronic homelessness but do not solve it. Investing in Housing First, which is a proven, evidence-based intervention, will provide immediate benefits by dramatically reducing chronic homelessness in communities across Ontario. Up to 69% of the costs of the Housing First intervention are offset by savings in other societal costs, such as shelter and health care costs.

Overview: Homelessness in Ontario

Homelessness issues persist in Ontario. The first province-wide Point-in-Time (PiT) count, an enumeration effort to identify the number of people experiencing homelessness on a single night, identified more than 21,000 people experiencing homelessness in Ontario in 2018.[3] Studies using data from hospital administrative records have estimated that close to 55,000 people in Ontario experienced homelessness over the 10-year period from 2006 to 2016.[4]

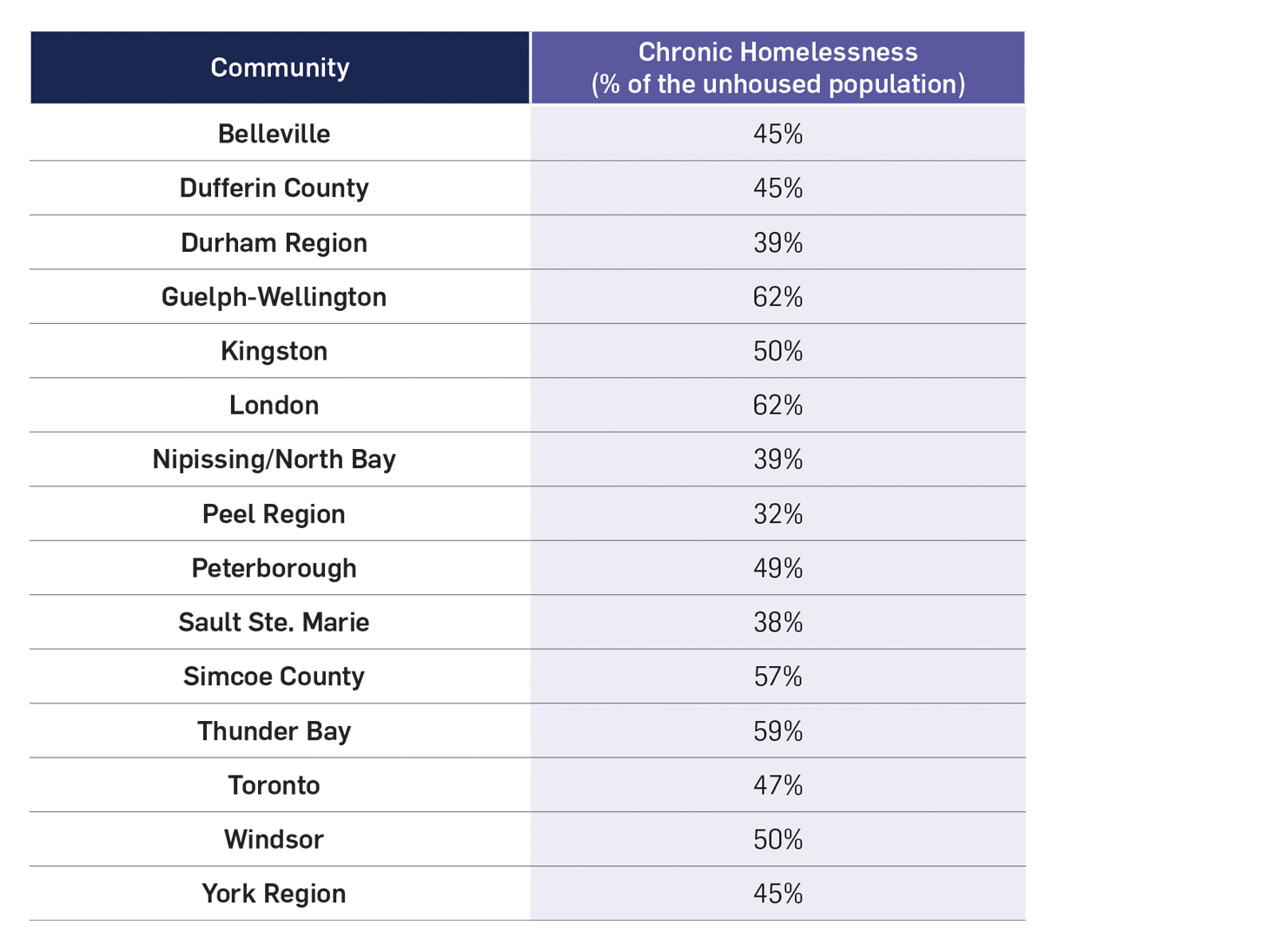

In recent years, the number of people experiencing chronic homelessness (i.e., people who have been homeless for at least six months over the past year) has also risen. The 2018 Ontario PiT Count found that 55% of respondents were chronically homeless.[5] The table shows a snapshot of the percentage of unhoused people who are experiencing chronic homelessness in various Ontario communities.[6]

The Province of Ontario previously committed to ending chronic homelessness by 2025 in the 2016 Long-Term Affordable Housing Strategy. This goal aligns with the National Housing Strategy, which commits to reducing chronic homelessness across Canada by 50%.[7] A commitment to end homelessness was also presented in the Province of Ontario’s Poverty Reduction Strategy, 2014-2019. The subsequent update to the strategy, Poverty Reduction Strategy, 2020-2025, does not refer to ending homelessness.

The Current Response to Homelessness in Ontario

The provincial Housing Services Act, 2011 recognizes that it is in the interests of the province to develop a housing and homelessness system that is focused on addressing the housing needs of people to achieve positive outcomes. The Housing Division of the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing leads these efforts toward a responsive housing and homelessness system. The provincial government is responsible for administering funds to 47 municipal service managers to implement programs designed to prevent, reduce, and end homelessness.

Of all levels of government, the province provides the majority of funding for housing and homelessness services.[8] The Office of the Auditor General of Ontario reported that in 2019/20, the province provided 63% of all housing and homelessness funding in Ontario, followed by municipalities (28%) and the federal government (9%). Provincial funding is primarily allocated under two programs: Community Homelessness Prevention Initiative (CHPI) and Supportive Housing Investments. The majority of the funding is spent on emergency shelter solutions. In Toronto, for example, 55% of funding is spent on emergency shelter solutions, whereas 4% of funding is spent on housing with related supports.[9]

Recommended Response: Targeted Investment in the Housing First Model

Current practices to address homelessness rely largely on a crisis-focused response (e.g., emergency shelters). Although an important part of the homelessness system, emergency shelters are a stopgap measure and will never reduce chronic homelessness. We need to shift the focus to programs and policies that prevent homelessness and support successful exits out of homelessness.[10] One such intervention is Housing First – a proven intervention that works.

Housing First programs provide immediate access to housing for individuals experiencing chronic homelessness who have severe mental health and substance use challenges. There are no preconditions to receiving housing. Rent subsidies are provided and community-based supports are typically offered through Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) for individuals with high needs or Intensive Case Management (ICM) teams for individuals with moderate needs.[11]

Evidence on Housing First. The Housing First model has been extensively researched and evaluated. The largest and most rigorous evaluation of the model took place in Canada.[12] The At Home/Chez Soi project was conducted from 2009 to 2013 in five cities across the country: Moncton, Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver, and Winnipeg. Using a randomized-controlled trial methodology, 2,148 individuals experiencing chronic homelessness and mental health challenges were randomly assigned to receive Housing First services or the standard care in their community. Results from the study found that, over a two-year period, individuals enrolled in Housing First spent an average of 73% of their time in stable housing, compared to individuals receiving standard care, who spent an average of 32% of their time in stable housing.[13]

Over a six-year period, research from the Toronto site of At Home/Chez Soi found that participants with high needs assigned to Housing First spent 85% of their time stably housed, compared to participants with high needs assigned to treatment as usual, who spent 60% of their time stably housed.[14]

Cost-Effectiveness. Participants in Housing First spend less time in institutions such as hospitals, prisons, jails, and addiction treatment facilities, and have lower levels of outpatient hospital visits than participants receiving treatment as usual. Depending on the level of need of Housing First participants, different cost offsets occur. For Housing First participants with high needs who received ACT services, there was a cost offset of 69%, resulting from reductions in costs for stays in emergency shelters and other services.[15] For Housing First participants with moderate needs who received ICM services, this cost offset was 46%.[16] So, as Housing First assists individuals experiencing chronic homelessness to move into permanent housing with supports, the program costs are offset by savings in other publicly funded areas (e.g., shelters, hospitals, correctional facilities).

Adaptations to Specific Populations. Housing First has been successfully adapted to meet the specific needs of ethno-racial people,[17] Indigenous people,[18] rural populations,[19] young people,[20] 2SLGBTQ+ young people,[21] and domestic violence survivors.[22]

How to Move Forward

Near-term Actions

- The Province of Ontario should re-commit to ending chronic homelessness. As outlined in More Home, More Choice: Ontario’s Housing Supply Action Plan,[23] all Ontarians should be able to find a home that meets their needs and their budget.

- The Province of Ontario should invest in Housing First programs. Housing First programs are evidence-based and the success of the program has been demonstrated in the Ontario context.

- Increase access to community-based mental health supports for Housing First programs, particularly ACT services, funded through the Ministry of Health.

- Accelerate the development of rent-geared-to-income housing that is affordable in perpetuity, including supportive housing that is aligned with the Housing First model.

- Ensure that specific populations disproportionately impacted by homelessness and housing insecurity, such as Indigenous people, Black people, women and gender-diverse people, 2SLGBTQ+ people, and people with disabilities, have equitable access to Housing First services.

Longer-term Action

- As outlined in the Auditor General of Ontario’s Value for Money Audit: Homelessness, the Province of Ontario lacks a coordinated approach to targeting homelessness. In keeping with the Auditor General of Ontario’s report, we recommend the creation of a cross-ministerial provincial division to address homelessness. This division should include representation from multiple ministries and lead the monitoring of investments toward eliminating chronic homelessness. The goal would be to achieve greater coherence and coordination across government programs and services.

Dr. John Ecker is Research Manager at the MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions, St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Toronto.

Dr. Stephen Hwang is the Director, MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions, Unity Health Toronto, and a professor of medicine at the University of Toronto.