Policy Papers

Grow Ontario Stronger: A Framework for the Ontario Government’s Post-Pandemic Recovery Plan

Sean Speer, Drew Fagan and Luka Glozic explore the unprecedented damage to Ontario's economy in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. This paper offers recommendations to help restore Ontario's economy and boost growth.

Executive Summary

As the Ontario Jobs and Recovery Cabinet Committee develops the provincial government’s plan for the post-pandemic recovery, its members ought to consider that:

- Boosting the province’s economic growth is a crucial precondition for employment, innovation, investment, and higher living standards.

- Ontario’s economic sluggishness predates the COVID-19 crisis. The province’s rate of economic growth has been falling decade-over-decade for the past fifty years. Average annual GDP growth per decade was 4.01 percent between 1960 and 2000. It has been just 1.74 percent since 2001.

- Ontario’s overall economic performance is generally weak relative to the rest of Canada and among neighbouring U.S. states. Ontario’s slow economic growth and poor productivity record have contributed to a decline in its GDP per capita relative to U.S. states such as New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Illinois.

- There are various secular headwinds holding back economic growth in the province including: slowed export growth (impacted by the decline of manufacturing); weak productivity growth; low business investment; poor innovation; and aging demographics.

- The general understanding of pro-growth policies is evolving to reflect both traditional policy levers such as taxation and regulation as well as newer policy levers such as childcare and public transit. A long-term growth strategy should draw on both sets of policy levers to support “inclusive growth” in the province.

- Several peer jurisdictions in Canada and the United States have developed long-term growth strategies rooted in the goal of inclusive growth. Saskatchewan and Illinois, in particular, have strong models that rely on evidence and data to set out clear, measurable goals that are accompanied by policy actions to support higher rates of economic growth and productivity.

- The Ontario government should follow suit with its own long-term growth strategy as part of its post-pandemic recovery planning. The provincial government should dedicate itself to a plan focused on long-term economic growth that is inclusive and driven by higher rates of productivity.

- Forthcoming Ontario 360 policy papers will put forward policy recommendations to detail a provincial long-term growth strategy. These papers will focus on policy areas such as post-secondary education, government procurement, energy policy and manufacturing.

Introduction

The COVID-19 crisis has been an unprecedented shock to Ontario’s economy. It is hard to overstate how damaging it has been to investment, consumer spending, and employment. It is not yet known how much its economy shrank in the second quarter, but the country-wide drop of 11.5 percent, which amounts to the largest quarterly decline on record, is probably a good indication.[1]

Dealing with the immediate public health risks of the pandemic remains the top priority. Concerns about rising case levels have recently caused the Ontario government to impose more stringent rules for public gatherings and increase financial penalties for breaking them. It is a reminder that the transition to a sustained economic recovery will be slow and iterative.

But policymakers still must be planning ahead. This work is being carried out by the Ontario Jobs and Recovery Cabinet committee. Its mandate is to develop and oversee a post-pandemic recovery plan, with a particular focus on “stimulat[ing] economic growth and job creation.”[2]

The committee is right to prioritize economic growth as part of its post-pandemic policy planning. This may seem axiomatic, but it bears repeating, especially given the depth of the current crisis: a dynamic, growing economy is an essential ingredient for a compassionate, innovative, and prosperous society.

Economic growth is not an end in and of itself. It is a crucial precondition to addressing many of the challenges facing Ontario, including with respect to public finances (such as funding for education, health care, and social services), employment, wages, and, ultimately, living standards.

Boosting growth is not just an imperative because of the COVID-19 crisis, either. Ontario’s economic growth has been slowing for the past several decades. Average annual growth in the decade prior to the coronavirus was 1.74 percent. This is far below the annual rate of 3.06 percent that the province averaged in the two decades between 1981 and 2000.

Ontario is hardly alone in this regard. Most advanced economies have experienced sluggish growth over the past two decades or so. The cause of this sluggishness is the subject of considerable debate. Slowed innovation and productivity, the unique characteristics and features of the digital economy, and aging demographics are cited as potential causes. Prior to the current crisis, there was already a growing concern that “secular stagnation” represented a “new normal.”

But while most advanced economies have underperformed over the past two or three decades, Ontario’s experience is notably stagnant. Just consider, for instance, that in 1981, Ontario’s GDP per capita was roughly the same as the neighbouring U.S. states but today it is $15,987 less than the combined average GDP per capita of New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Illinois. This shows that the province is not just stagnating like others, it is actually becoming poorer relative to peer jurisdictions.

Understanding how to restore economic growth and enhance productivity in Ontario will thus be key to the province’s post-pandemic future. Mitigating the effects of secular stagnation and closing the GDP per capita gap with its neighbouring states ought to be top priorities for provincial policymakers as they develop a post-pandemic recovery plan for Ontario.

The purpose of this Ontario 360 policy paper is to engage these issues. In particular, the paper will address the following questions:

- Why does economic growth matter for Ontarians and why should it be a priority for provincial policymakers?

- How has Ontario’s economic growth evolved over time? How does its economic growth in recent decades compare to the past? How does its overall economic performance compare to peer jurisdictions, including in the United States? And how does this performance compare within Ontario?

- Why has economic growth in advanced economies slowed in the past two decades or so? What can public policy do to mitigate these headwinds?

- What is the role of public policy to support economic growth? What policy levers must be considered as part of a growth-oriented strategy?

- What are peer jurisdictions doing to support long-term economic growth? What, if any, lessons are there for Ontario policymakers from these experiences?

- What does this all mean for Ontario policymakers?

By addressing this set of questions, the goal of this policy paper is to: (1) set out why Ontario policymakers ought to prioritize a policy framework that supports higher rates of economic growth as part of the province’s post-pandemic recovery plan, (2) build the case for a broader, more inclusive conception of the policy levers relevant to supporting economic growth, (3) highlight pro-growth lessons that Ontario policymakers can derive from peer jurisdictions, and, (4) start to populate a list of policy areas that will need to be part of a strategy to close the gap between Ontario’s recent rates of economic growth and its historic performance.

Fundamentally, though, the paper aims to establish the case that economic growth and productivity are influenced by public policy choices and that, as the Ontario government develops its post-pandemic recovery plan, it must actively choose to support a dynamic, growing economy now and for the future.

To this end, the Ontario government should develop and release a long-term growth strategy that draws on best practices (including with respect to outcome metrics, sector-specific strategies, and accountability mechanisms) from peer jurisdictions such as Saskatchewan and Illinois.

Why Does Economic Growth Matter?

It is worth starting out by understanding economic growth and how it translates into a wider set of measures of economic welfare for individuals and society. Economic growth is not an end; it is a means to the ends of greater opportunity, more and better jobs, and higher living standards.

Gross domestic product (GDP) refers to the total value of goods and services produced over a specific time period. Faster GDP growth reflects higher levels of output and, in turn, an expansion of the overall size of the economy.

Economic growth is often characterized as the result of people redeploying resources in ways that make them more valuable. Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Romer uses the metaphor of cooking in the kitchen to explain the process of innovation that undergirds economic growth. As he writes:

“To create valuable final products, we mix inexpensive ingredients together according to a recipe. The cooking one can do is limited by the supply of ingredients, and most cooking in the economy produces undesirable side effects. If economic growth could be achieved only by doing more and more of the same kind of cooking, we would eventually run out of raw materials and suffer from unacceptable levels of pollution and nuisance. Human history teaches us, however, that economic growth springs from better recipes, not just from more cooking. New recipes generally produce fewer unpleasant side effects and generate more economic value per unit of raw material.”[3]

Broadly speaking, there are two main sources of economic growth: growth in the size of the workforce and growth in productivity (output per hour worked) of that workforce. Either can increase the overall size of the economy but only strong productivity growth (stemming from the innovation process described by Romer) can increase per capita GDP and income. Productivity growth allows people to achieve a higher material standard of living without having to work more hours.

The process of economic growth and higher rates of productivity are important because they are typically associated with more job creation, rising incomes, and, ultimately, higher standards of living. The evidence is quite strong. Just consider:

- Basnett and Sen reviewed the empirical literature and found that economic growth has a powerful relationship with employment levels in advanced economies.[4] An et al. (2016) found that in Canada every 1-percent increase in GDP was matched by an increase in employment of 0.6 percent or higher.[5]

- Dopke investigated the effects of economic growth on employment across European states and similarly found a positive relationship between higher rates of growth and more employment in every country, though the intensity varied among them.[6]

- Seyfried examined the link between economic growth and employment in the ten largest U.S. states and also found a significant positive relationship. The effects of economic growth stretched over several quarters, and so there often could be a significant lag between the initial increase in economic growth and its effects on the economy, which suggests medium- and even long-term benefits from higher rates of economic growth.[7]

- Khan found that robust economic growth had a powerful effect on poverty reduction, especially when combined with policy efforts to reduce income inequality. Weak growth, by contrast, can harm poverty reduction even with ongoing redistribution policies.[8]

- Pethokoukis and Strain have argued that, although higher economic growth does not lift all boats equally or at the same time, in the long run it is a critical ingredient for rising incomes and living standards. Strain, in particular, shows that if US real GDP growth had been 1-percent lower over the previous four decades, GDP per capita would today be 25 percent lower in the United States.[9]

- Romer, who has been a pioneer in our understanding of economic growth, its causes, and effects, has similarly shown the long-run benefits of economic growth to income levels and living standards.[10]

- In a challenge to the Easterlin Paradox, which suggests diminishing returns to happiness from increased growth, Stevenson and Wolfers found that the link between rising incomes and personal happiness remained absolute and that those enjoying materially better circumstances enjoyed higher well-being.[11]

- Friedman in his essay, “The moral consequence of economic growth”, has even argued that economic growth is a key foundation for pluralism, tolerance, diversity, and democracy.[12]

- Dynan and Sheiner have argued that, although gross domestic product is not a comprehensive measure of well-being, it is a good proxy for different measures of economic well-being such as consumption and, thus, remains a useful and important tool for policy analysis and economic evaluation.[13]

The upshot: sustained levels of economic growth are a precondition for a wide range of positive economic and social outcomes.

A big reason why is what economist Tyler Cowen refers to as the “magic of compounding growth.” If real GDP per capita grows at 1 percent per year, it takes 70 years for Ontarians to double their real per capita income. At 1.5 percent per year, it only takes 47 years; at 2 percent, 35 years; and at 2.5 percent, 28 years. These growth rates are in the range of Ontario’s historical performance (see next section), so one can see how small, plausible increases in economic growth lead to large differences in future wealth and living standards. Even tiny changes add up: the difference between 2.0 percent and 2.2 percent growth means the economy is 8 percent larger in 25 years.

A fast-growing economy will still experience disruption and shocks along the way. It does not arrest the forces of Schumpeterian creative destruction – in fact, it likely accelerates them. There will be churn in industries and jobs and the inevitable creation of so-called “winners and losers.” Policymakers must be cognizant of the negative effects on certain people and places. Previous Ontario 360 policy papers, for example, have set out policy reforms to improve the province’s income support and skills-training programming.[14]

But, over the long term, a growing economy and rising rates of productivity are the best means for expanding opportunity, reducing poverty, and raising living standards. As Harvard economist Dani Rodrik has put it: “Historically nothing has worked better than economic growth in enabling societies to improve the life chances of their members, including those at the very bottom.”[15]

Of course, GDP growth is not the only or even necessarily the best economic measure. It does not account for various forms of economic behaviour (including for instance volunteer services or stay-at-home parenting) and it does not say anything about the distribution of economic resources or the types of industries and firms that are shaping economic activity. There are also growing questions about whether gross domestic product is fully capturing new and emerging forms of economic activity.

But it would be wrong to neglect the importance of economic growth and productivity over the long term. As economist Paul Krugman has observed: “Productivity is not everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.”[16] Policymakers cannot afford to neglect these issues if they want to have a growing, dynamic, and prosperous society over time. The COVID-19 crisis has only reinforced the need to restore economic activity in Ontario and reach for higher levels of economic growth than prior to the pandemic.

How Has Ontario Performed in Recent History?

Ontario has been Canada’s major economic engine since Confederation. But it has underperformed in recent decades across a range of economic indicators, including business investment, incomes, jobs, and public finances.[17] This weak performance has occurred regardless of which political party was in power.

Something as complex as the economy is not shaped by monocausal forces. Different research highlights different factors behind Ontario’s relative performance. But the scholarship generally points to:

- Slowed export growth: Ontario’s economy has historically been driven by exports, but its export growth has slowed to among the lowest in North America in recent years. The relative decline of its manufacturing sector is one of the main factors behind the province’s relatively poor export performance.[18]

- Weak productivity growth: The province’s productivity growth fell to an average of 1.1 percent between 1998 and 2018, which was below peer jurisdictions in the United States and Canada.[19] In fact, a 2015 report by the Institute for Competitiveness and Prosperity observed that, in the goods-producing sectors, an Ontarian worker produced roughly 28 percent less than the median worker in 20 peer jurisdictions in North America.[20]

- Low business investment: A related problem is that Ontario significantly lags its peers in business investment across virtually all sectors, which has also contributed to productivity losses.[21]

- Poor innovation: Ontario has had lower gross expenditures on R&D (including businesses, post-secondary institutions, and government) than its non-Canadian peers for the past two decades. The portion of the province’s GDP dedicated to R&D expenditures has steadily fallen since 2001, while U.S. and other international peers have increased their GDP-weighted expenditures.[22]

- Aging demographics: The province’s aging population is constraining the growth of its labour force. The average annual rise in the labour force was 1.4 percent between 1982 and 2019 and future projections anticipate that it will fall to 0.9 percent per year, fueled mostly by migration.[23]

These causes are interrelated and it is difficult to isolate their relative importance. But the outcomes are nevertheless clear: Ontario’s average rates of economic growth have fallen steadily over the past several decades.

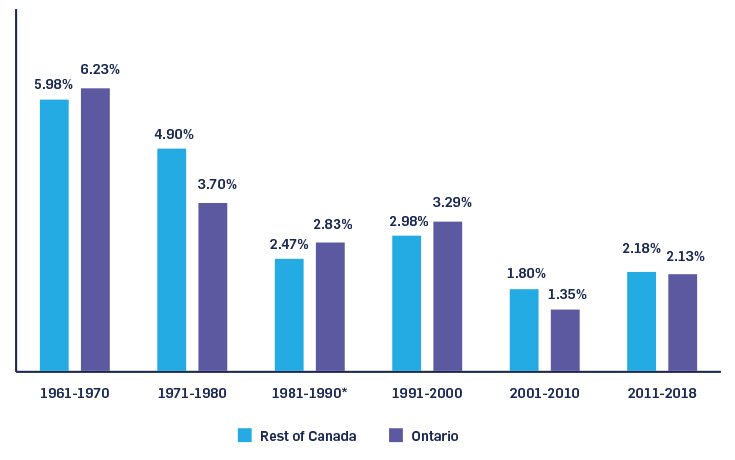

The province experienced average real GDP growth of 6.23 percent between 1961 and 1970. That has fallen steadily over subsequent decades and reached barely 2 percent between 2011 and 2018. In fact, average real GDP growth by decade for the province was 4.01 percent for the 40 years between 1960 and 2000. By contrast, it has been 1.74 percent since 2001 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Ontario Average Real GDP Growth By Decade, 1961-2018

Source: Statistics Canada 2019, 2010.

*GDP data from 1981 onwards is drawn from official statistics based on the expenditure method. GDP data from 1961-1980 is drawn from statistics calculated by an average of the income and expenditure method.*

Ontario’s slowed economic growth is even evident when one compares its performance with the rest of the country. Its average growth rate between 2000 and 2018 was 1.74 percent compared to 1.99 percent in the rest of the country (see Figure 2). As stated previously, small differences can add up over time.

Figure 2: Ontario And The Rest Of Canada (Excluding Ontario) Average Real GDP Growth By Decade, 1961-2018

Source: Statistics Canada 2019, 2010.

The story is not different beyond Canada’s borders. One common means of comparing different jurisdictions is GDP per capita. It enables us to compare Ontario’s standard of living to other jurisdictions by accounting for different economic and population sizes and adjusting on an apples-to-apples basis.

It is not a foolproof method of comparing jurisdictions. It does not account, for instance, for income and wealth distribution. But GDP per capita provides a sense of how productive and wealthy a society is relative to others.

What does this measure tell us?

The results may surprise many Ontarians. Most would probably assume that we live in a rich society but the truth is that we are, in overall terms, poorer than most U.S. states, including several neighbouring ones. It was not always the case. Ontario’s GDP per capita was $35,131 in 1981, which at the time was higher than Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. But, by 2018, Ontario’s GDP per capita was $54,342, which is now lower than all of these states.[24]

In fact, Ontarians are now poorer (as measured by GDP per capita) than those living in all of its neighbouring states, including the ones listed above as well as New York, Minnesota, and Illinois. As of 2018, Ontario’s GDP per capita was $15,987 less than the combined average of New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Illinois (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Figure 3: Real GDP Per Capita For Ontario And Neighbouring U.S. States (PPP, $CAD), 1981 To 2017

Source: Statistics Canada, United States Census Bureau, United States Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2010 and 2019.

* In 1997 the US GDP calculation switched from the SIC to the NAICS classification.*

As mentioned above, there are various factors – ranging from low business investment and poor innovation to an aging population – that have contributed to Ontario’s middling economic growth and productivity rates prior to the COVID-19 crisis.

These issues are exacerbated by the province’s uneven regional performance, which has been the subject of previous Ontario 360 analysis.[25] To the extent that the province has experienced increases in economic activity, productivity, and employment, they have been mostly concentrated in the province’s major centres. It is notable, for instance, that, of the 865,000 net new jobs created in the province between January 2008 and August 2019, nearly 90 percent were concentrated in Toronto and Ottawa. Rural parts of the province experienced a net loss of 75,000 jobs over this period.[26]

The key takeaway is that Ontario’s economic growth and productivity rates have been slowing for years. This probably understates the problem to the extent that the province’s increases in economic growth, productivity, and employment have been highly concentrated in major cities over the past two decades or so. The rest of the province – particularly rural communities and those facing de-industrialization – has struggled even more.

Weak economic growth and productivity rates can have various consequences. They can manifest themselves in less employment, lower wages, and poorer living standards. They also impact public finances. The provincial budget estimates that a 1-percentage point change in nominal GDP (real GDP plus inflation) affects revenue by approximately $705 million.[27] Faster economic growth translates into higher provincial revenues and greater fiscal capacity to pay for key social programs.

As part of the post-pandemic recovery planning, then, the main question for Ontario policymakers should be about how to catalyse higher rates of economic growth and productivity and extend their benefits more widely across the province. This requires understanding how different policy interventions might be able to pull the province out of its economic doldrums.

What Is Secular Stagnation? Can It Be Mitigated?

The previous section outlined Ontario’s recent record on economic growth and productivity. This section aims to place the province’s performance in a broader context to better understand what factors are within the control of Ontario policymakers and which ones may be less responsive to provincial policies.

Ontario’s experience is far from unique. It has occurred against a backdrop of a broader debate about “secular stagnation” to describe the sustained period of slower economic growth in advanced economies that has followed the 2008-09 global recession.[28]

The idea of secular stagnation is most prominently associated with former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers. His basic argument is that slow growth in advanced economies is not a product of the typical business cycle but instead reflects deep, structural issues – namely a rise in savings and a corresponding drop in investment– that are immune to traditional supply-side policy responses.[29] His argument is that the slowed economic growth reflects a structural drop in aggregate demand and that only a mix of demand-side policies such as infrastructure spending and tax reform will mitigate these secular challenges.[30]

Other economists such as Robert Gordon agree with the diagnosis of protracted stagnation but may disagree on its causes. Gordon’s work, for instance, points to supply-side challenges rooted in lower productivity rates.[31] His basic argument is that modern society has reached a technological frontier and future growth will be constrained by an inability to break out of this technological stagnation. His work is marked by a pessimism about the role of public policy to reverse the trends of secular stagnation.

The literature points to various other explanations including globalization and the rise of China, the decline of manufacturing, and so on, as possible causes for these trends.[32] But, irrespective of the relative role of these different issues, most economists agree that the effect is that economic growth in advanced economies has slowed and will continue to face downward pressures.

This analysis is important context for Ontario policymakers as they develop the province’s post-COVID recovery plan. They must be cognizant of secular stagnation. But they must also avoid a sense of fatalism. Secular stagnation is not destiny; there is room for public policy to mitigate its effects and support higher levels of economic growth and productivity.

As Tiff Macklem, the current Bank of Canada governor (and a former Ontario 360 author) wrote with co-author Jean Boivin, in 2014: “Better public policies and an improved global financial architecture can unleash significant additional growth.”[33]

Macklem and Boivin are not alone. Recent Nobel Prize winner Bill Nordhaus argues that the current technological stagnation is temporary and that emerging areas such as quantum computing and machine learning have the potential to serve as a catalyst for future economic growth and productivity.[34] Similarly Bergeaud, Antonin and Lecat argue that productivity slowdowns have been common in history and reflect the natural catch-up between innovation, broad-based adoption, and resulting productivity enhancements. They highlight, for instance, a comparison between the delayed productivity gains from computing and the process that followed the invention of electricity.[35]

There is plenty of room, then, for public policy – including tax and regulatory reform, public infrastructure investments, incentives for private capital investment, greater public support for basic and applied research, and so on – to support higher rates of innovation, productivity, and ultimately economic growth. Even if the impacts are on the margins, marginal differences matter over time.

What Policy Tools Should Be Part of a Growth Strategy?

Conventional economic thinking has tended to focus on macroeconomic policy and the overall business climate for investment, innovation, and entrepreneurship. This perspective has mostly conceived of a limited role for government. Public policy has been about setting the conditions for market actors rather than shaping market outcomes. Economist Bradford DeLong has described this prevailing policy consensus as a “very light policy and regulatory touch.”[36]

In practical policy terms, this has placed an emphasis on inflation targeting, sound public finances, a stable monetary policy, and a general skepticism about government intervention in the economy.[37] The basic idea was for policymakers to focus on setting the overall market conditions, but otherwise let market forces and individual actors shape economic outcomes, including the distributional results. Redistributive policies could then minimize the market’s unequal allocation of resources among people and places.

This economic policy paradigm has commonalities across advanced economies. Canada is no exception. It first found expression, at least at the forefront of public policy, in the 1985 Royal Commission on the Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada. It has since come to shape public policy at the federal and provincial levels, including with regard to privatization, trade liberalization, tax reductions, de-regulation, and so on. This overall policy framework has contributed to a range of positive economic and social outcomes. But it has also contributed to higher levels of income inequality and growing geographical disparities.

There are now challenges to this economic paradigm. They were catalysed by the global financial crisis in 2008-09 and have only accelerated in the context of COVID-19. One concern is the level of income and geographical inequality in our society. Another is the extent to which the rise of intangible capital (including software, data, algorithms, and intellectual property) has shown itself immune to aspects of the old economic paradigm. And another yet is the rise of China and the challenge it poses to the post-Cold War global trading system.

The upshot: there is now new thinking coming to prominence about the goals of economic policy as well as the policy levers relevant for a pro-growth strategy. The main alternative to the current policy paradigm is often defined as “inclusive growth.”

Inclusive growth is defined by the OECD as “economic growth that creates opportunities for all groups of the population and distributes the dividend of shared prosperity.”[38] The basic idea is not to challenge economic growth as an important policy objective but to use market shaping policies to ensure that the benefits of economic growth are more broad-based. There is also growing support for a more active role for governments in shaping – rather than just enabling – technological innovation and adoption in the market economy, particularly in the areas of intangible capital.

The idea of inclusive growth has received significant attention among global leaders and international organizations. Valerie Cerra, division chief at the IMF’s Institute for Capacity Development, for instance, has called inclusive growth the “pivotal economic policy challenge of our time.”[39] UN Secretary-General António Guterres has called on business leaders to support a push for inclusive growth.[40] This has been echoed by former IMF director Christine Lagarde[41] and the leaders of the G20,[42] and increasingly put into practice by the OECD[43] and regional organizations like the African Development Bank.[44]

The main effect of this newfound emphasis on economic inclusion is to broaden the set of policies relevant to an economic growth strategy. Traditional policy levers for economic growth are not now obsolete but there is greater interest in new policy areas – such as childcare, public transit, and housing affordability – in supporting higher rates of economic growth and productivity. One might think of this change in terms of augmenting the traditional policy levers for economic growth with a broader set of policy tools to reflect the unique features and characteristics of intangible capital as well as political economy concerns about inclusivity.

One of the key insights of this new thinking on “inclusive growth” is to revisit assumptions about the “efficiency-equity” trade-off inherent in policymaking. The conventional view has been that an emphasis on greater equity and inclusion would come at the expense of economic efficiency and vice versa.[45] Taxation is a good example. The idea was that more progressivity – including higher marginal rates on top-income earners – might achieve greater equity but at the expense of weaker incentives for investment, entrepreneurship, and other economically-productive activities.[46]

It is not that there is no trade-off between efficiency and equity. But new research shows that certain policy areas – including childcare – can positively contribute to both efficiency and equity objectives.[47] Policy areas such as competition law, labour market supports (including skills training and wage subsidies), childcare, public transit, affordable housing (including inclusionary land-use policies), and education reform are examples of policy areas that are increasingly considered as part of a pro-growth strategy.

The bottom line: a combination of traditional and newer growth-oriented policies will be needed to break out of secular stagnation and accelerate economic growth and productivity gains. This will require a combination of tax reform, regulatory reform, human capital investments (including university, college, and apprenticeship education), support for R&D and innovation (including a role for government procurement), and high-quality infrastructure (including traditional and digital) as well as well-designed social policies including childcare, income support programming, and skills-training.

Ontario policymakers ought to think broadly, in other words, about the policies that form the province’s post-COVID recovery plan.

What Are Peer Jurisdictions Doing?

Other jurisdictions are certainly moving in this direction. They have started to develop long-term economic growth strategies that draw on a wide range of policy levers.

Such long-term planning is a major gap in Ontario’s policy framework. The province presently produces long-term budget projections, but it has not set out a vision for the province’s economy, including an understanding of its comparative advantages, how they relate to broader global trends, and how provincial policy can accentuate these advantages. A five- or ten-year economic policy framework would help to better situate policy decision-making and bring greater intentionality and coherence across ministries.

Across North America, Canadian provinces and American states are moving towards providing an economic framework for the next five or ten years. These plans are defined by being broad, comprehensive, and analytical, identifying strengths and weaknesses in their respective economies and policies to improve their standing locally and globally.

There are now, according to our estimates, 23 economic growth plans or strategies across the U.S. states. Many of these plans are influenced by the Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) framework developed by the U.S. Economic Development Administration (EDA).[48] The EDA is an agency inside the U.S. Department of Commerce with the mandate to provide grants and technical assistance to economically-distressed communities. Having an Economic Development Strategy is, in some cases, a condition for states or regions to be able to access the EDA’s funding programs.

The CEDS is a standardized strategy template with a common design and structure for states and regions to follow. They must include, for example, a summary background, SWOT Analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats), strategic direction/action plan and an evaluation framework.[49] The CEDS content guidelines also provide details for what is recommended to be included in each section.

The CEDS highlights key components of a growth plan, — such as regional clusters, workforce considerations, state of the regional economy, institutions of higher education, and so on. It also calls for community engagement and stakeholder input in their development. Recommended metrics include private investment, GDP per capita, household income, and job creation. It also encourages jurisdictions to find non-economic metrics to measure cultural, social, intellectual, environmental, and other assets which cannot be captured by this model.

Some states have recently created their own CEDS-structured plans. These include Alaska,[50] Rhode Island,[51] Delaware,[52] Vermont,[53] and Hawaii.[54] These plans follow the CEDS framework and have a five-year duration. The standardized structure encourages substantive and actionable policy details and permits inter-state comparisons. Several larger U.S. states, by contrast, have developed their own economic growth strategies that diverge from the CEDS model in detail or structure. These include several four- or five-year plans by Virginia,[55] Oregon,[56] Florida,[57] Ohio,[58] Michigan,[59] Oklahoma,[60] and New Jersey.[61] There are also some 10-year economic plans in states such as Maine[62] and North Dakota.[63]

We have reviewed these plans and strategies to understand their strengths and weaknesses and commonalities and differences. Some are better than others. There is a mix of clear economic metrics and -directional aspirations, overall economic goals and sectoral strategies. The level of policy detail varies. Some read primarily as political documents while others are more actionable economic strategies. In general, every plan emphasizes innovation, inclusive growth, and workforce transition and skills training.

There are also several growth plans in Canada. The New Brunswick government, for instance, has released two growth plans for the periods from 2012 to 2016 and 2016 to 2020. The most recent plan is based on five general pillars of people, innovation, capital, infrastructure, and agility but it is missing specific details in some of its action items and mixes specific (e.g., workforce increases) and non-specific (e.g., entrepreneurs have access to more capital) goals. The Governments of Newfoundland and Labrador,[64] Prince Edward Island,[65] British Columbia,[66] and Manitoba[67] have also produced economic strategies. Like the U.S. state plans, there is a varying degree of empirical analysis, clear economic or sectoral goals, and policy specificity. Two of the strongest state and provincial growth plans are Saskatchewan’s[68] and Illinois’.[69] They are worth further analysis.

The Saskatchewan and Illinois plans represent the aspirations of different governments with divergent economic profiles and political preferences. But they share broadly in their analytical framework, comprehensiveness, use of clear metrics and targets, and detailed policy prescriptions to achieve objectives.

They are also developed on the logic and assumptions of inclusive growth – that is, they share an underlying assumption that economic growth should serve to improve living standards and economic mand social well-being for the broadest share of the public.

Saskatchewan’s Growth Plan

The Saskatchewan government’s 10-year plan, which was released in 2019, covers the period up to 2030. It builds on a previous growth plan that was released in 2012 and covered up to 2020.[70]

The plan sets out 30 clear growth-oriented goals that range from the overall economy, such as population size and private capital investment targets, to the sectoral such as agricultural exports and tourism levels. It also sets out 20 actions to achieve these goals. The goals are clear and measurable, such as to increase the value of provincial exports by 50 percent. The actions tend to be a bit more generalized, such as to expand Saskatchewan’s export infrastructure.

But within the various goals there is considerable specificity with respect to policies that the government intends to undertake. As an example, the growth plan highlights tax policy changes – including reinstating sales tax exemptions for exploratory and drilling activity – as part of its plan to achieve the goal of increasing annual uranium sales to $2 billion and potash sales to $9 billion. There are similarly detailed policy commitments throughout the document. In overall terms, it amounts to a comprehensive agenda across the range of policy areas for which the province is responsible.

This exercise of setting clear goals and then identifying policy reforms to meet these goals is highly valuable. It can discipline and focus policymaking, provide greater certainty for businesses and investors, and create an accountability tool for voters.

If there is one weakness with Saskatchewan’s plan, it could benefit from a stronger evidentiary foundation. At times, it reads as if virtually every sector and part of the economy is prioritized. It is also not clear enough how the various goals were set and how ambitious they are relative to historic trends. The original provincial growth plan, by contrast, seems to have better utilized data and evidence on market share, patents, business expenditure on R&D, and other metrics to focus on the most dynamic and productive parts of the provincial economy.

But, nevertheless, the Saskatchewan growth plan is an excellent model for the Ontario government to emulate. It is clear, measurable, and detailed, and it places economic growth in a broader vision for the province. It outlines various areas – including public investments in mental health services and support for vulnerable citizens, for instance – that are ultimately underwritten by higher rates of economic growth.

A Plan to Revitalize the Illinois Economy and Build the Workforce of the Future

Illinois’ growth plan, which was released in 2019, covers a five-year period. It is the state’s second growth plan. There was a similar plan released by the previous governor in 2014.[71]

The Illinois plan differs a bit from the Saskatchewan plan. The biggest difference is it generally eschews overall growth-oriented goals, such as levels of economic activity and employment, and instead focuses on key sectors where the state thinks it is “positioned to compete globally for talent and investment.” It targets six industries in particular – (1) agribusiness and AG tech, (2) energy, (3) information technology, (4) life sciences and healthcare, (5) manufacturing, and (6) transportation and logistics – based primarily on their relative employment footprints in the state. The plan then identifies opportunities and challenges facing these key industries and outlines policy actions taken to date and planned for the future to better support them.

Information regarding the basis for the selection of the key industries is lacking. It is possible that these are the six industries in which Illinois has a pre-existing comparative advantage, but the plan fails to demonstrate this using data and evidence.

It is far from clear that these are the right sectors for the state government to base its five-year growth strategy around. It is also not clear how the state government will measure success in these industries.

There are flaws in each of these documents, then, and in others we reviewed. If the Ontario government were to orient its long-term growth strategy around key sectors, it would need to draw on a stronger evidentiary basis. Employment ought to be an indicator but so too should be global market share, patents, business expenditures on R&D, and other metrics. Similarly, it ought to define how Ontarians can ultimately judge if and how the strategy is working.

Still, within the six key industries set out in the Illinois plan, the plan does a good job of seeking to understand the opportunities and challenges within the state. This is a useful innovation relative to the Saskatchewan plan. This focus on sectoral challenges is useful for framing the role of public policy to address specific problems. Take information technology for instance. The plan identifies that Illinois-based information technology firms struggle to compete for talent with companies in Silicon Valley, New York and Boston. This sectoral level understanding enables policymakers to produce better targeted policy solutions.

The Illinois plan’s policy specificity is, as a result, quite detailed. It enumerates several policy actions to address these specific challenges identified for each of the key industries. This is a positive sign that the different ministries that comprise the state government are coordinating their policies as part of these sectoral strategies.

It also reflects a focus on inclusive growth. Not only does it highlight traditional growth issues such as foreign investment and exports, it also considers the economic circumstances of underrepresented groups such as justice-impacted populations. This emphasize on inclusivity is something that Ontario policymakers ought to take note of and incorporate into a long-term growth strategy for the province.

What Does All This Mean For Ontario Policymakers?

The key takeaways are:

- High rates of economic growth and productivity are closely correlated to employment, innovation, investment, and higher living standards. Small differences in economic growth compound over time and can have a marked effect on a broad range of economic and social outcomes. Economic growth is not an end and itself. But it matters a great deal for a society’s economic and social well-being. It is a crucial precondition for Ontario to respond to the opportunities and challenges that it will invariably face in the coming years.

- Ontario’s rate of economic growth has been falling decade-over-decade for the past fifty years. This sustained drop in economic growth is not unique to Ontario. The trend line has been similar in other jurisdictions.

- But the province’s comparative economic performance is poor. Its GDP per capita relative to U.S. states such as New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Illinois has declined. Just consider that, in 1981, Ontario’s GDP per capita was roughly the same as these states and today it is $15,987 less than their combined average GDP per capita.

- There are various secular forces holding back economic growth in the province including: slowed export growth (including the decline of manufacturing); weak productivity growth; low business investment; poor innovation; and aging demographics.

- The provincial government should dedicate itself to a policy strategy focused on long-term economic growth and higher rates of productivity. This is the best means of digging out of the COVID-19 economic crisis in the short-term as well as improving Ontarians’ living standards in the long-term.

- Conventional thinking about the role of government in supporting economic growth and productivity has changed. New scholarship and policy thinking places a greater role on a broader range of policies – including childcare, public transit, and housing affordability – in the name of “inclusive growth.” The traditional policy levers for economic growth are being augmented to reflect the unique features and characteristics of intangible capital as well as political economy concerns about inclusivity.

- Several peer jurisdictions in Canada and the United States have developed long-term growth strategies rooted in the goal of inclusive growth. Saskatchewan and Illinois, in particular, have strong models that Ontario policymakers ought to review closely. Clear, measurable goals and accompanying policy actions can create discipline and focus for policymaking, provide greater certainty for businesses and investors, and create an accountability tool for voters.

- The Ontario government should follow suit with its own long-term growth strategy as part of its post-pandemic recovery plan. Forthcoming Ontario 360 policy papers will put forward policy recommendations to detail such a long-term growth strategy, with the goal of higher rates of economic growth and productivity for the Province of Ontario.

Drew Fagan is a professor at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy and a former Ontario deputy minister.

Sean Speer is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy.

Luka Glozic is an independent policy consultant and recent graduate from the Munk School of Public Policy and Global Affairs. He specializes in long-term economic, labour and urban policy issues. He was previously a researcher for the 2019 independent review of the Ontario Workplace Safety Insurance Board. He is currently engaged with research and analysis for the Ontario 360 project.