Policy Papers

A Post-Pandemic Growth Strategy For Canada

Sean Speer, Drew Fagan and Luka Glozic examine current economic planning efforts by Canadian policymakers, how they compare to other jurisdictions, and how best to plan for the post pandemic future.

Executive Summary

As the federal government develops its plan for the post-pandemic recovery, it ought to consider that:

- A faster rate of economic growth in Canada is a crucial precondition for employment, innovation, investment, and higher living standards. It may also be an antidote to the rise of polarization, populism, and the zero-sum thinking that underpins them.

- Canada’s economic sluggishness long predates the COVID-19 crisis. The rate of economic growth has been falling decade-over-decade for the past fifty years. Average annual GDP growth per decade between 1960 and 2000 was 4.08 percent. It has been just 1.99 percent since the start of this century.

- Over this period, Canada’s overall economic performance – particularly with respect to productivity (GDP per hour worked or GDP per person employed), capital investment, R&D spending, and GDP per capita – has generally lagged peer jurisdictions in the G-7.

- There are various long-term headwinds holding back economic growth in the country including: weak productivity growth; low business investment; poor innovation; and aging demographics.

- But theories about “secular stagnation” should not cause policymakers to be fatalistic. Policy choices can make a difference, at the least on the margins.

- The general understanding of pro-growth policies is evolving to reflect both traditional policy levers such as taxation and regulation as well as newer policy levers such as childcare and public transit. A long-term growth strategy should draw on both sets of policy levers to support “inclusive growth.”

- Several jurisdictions, including many provinces and U.S. states, are developing long-term growth strategies rooted in the goal of inclusive growth. The Province of Saskatchewan, in particular, has a strong model that relies on evidence and data to set out clear, measurable goals that are accompanied by policy actions to support higher rates of economic growth and productivity.

- The Canadian government should follow suit with its own long-term growth strategy as part of its post-pandemic recovery planning. Ottawa should dedicate itself to a plan focused on long-term economic growth that is inclusive and driven by higher rates of productivity.

Introduction

The recent spike in COVID-19 cases has caused Canadian policymakers to focus on the pandemic at the possible expense of post-pandemic planning. Managing the spread of the virus understandably remains the overwhelming priority.

But, as Munk School fellow Robert Asselin recently wrote, we cannot afford to set aside post-pandemic policy development indefinitely.[1] Other countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and Australia have developed bold policy agendas to catalyse future growth when the pandemic eventually subsides. Canadian policymakers must match them if we are to compete for investment, innovation, and jobs now and into the future. As Asselin puts it: “Where is Canada’s economic vision for the future?”

Such a vision should put the goal of sustaining higher rates of economic growth near its centre. It is not that economic growth is an end in itself. But, as we outlined in a previous paper for Ontario 360, it is a crucial precondition to addressing many of the long-term challenges facing the country including with respect to public finances (such as funding for education, health care, and social services), employment, wages, and ultimately living standards.[2]

Canada’s rate of economic growth has slowed in recent decades. Consider, for instance, that the average growth rate per decade has generally fallen from nearly 6 percent in the 1960s to just over 2 percent since 2000.[3] We are not alone in this regard. Most advanced economies have experienced sluggish growth over the past two decades or so. The U.S. economy, for instance, has similarly averaged about 2 percent annual growth since the beginning of this century.[4]

The causes of this secular slowdown in advanced economies are multifaceted. A combination of aging demographics, slowed innovation and technological adoption, overhang of the global financial crisis, and even measurement issues are partly responsible. The consequences of a sustained period of slow growth are likely to be significant. Evidence shows that not only is slow growth associated with less investment, innovation, and employment, it can contribute to political polarization[5] and zero-sum thinking.[6] Economic stagnation can ultimately lead to an unhealthy and widespread perception that we have reached an “end of progress.”

The question is: What can federal policymakers do about it?

A starting point is to recognize that higher rates of economic growth and productivity are hardly outside of the scope of public policy. Policy choices can, if only sometimes on the margins, affect the economy’s overall trajectory – including achieving higher (or lower) rates of economic growth and productivity.

The key takeaway is that, as the federal government develops its post-pandemic recovery plan, it must actively choose to support a dynamic, growing economy now and for the future. It should commit itself to a renewed, future-oriented vision of economic growth and progress.

The purpose of this paper is to help inform and shape such a vision. Section One outlines the economic, political, and social effects of slowed economic growth. Section Two provides a historical primer on Canada’s economic performance – including with respect to how its economic growth rate, labour productivity, and GDP per capita compares with peer jurisdictions. Section Three draws on a considerable body of scholarship to consider the factors that have contributed to slower economic growth in Canada and other advanced economies. Section Four analyses the policy tools that may be part of a policy agenda for what is sometimes called “inclusive growth” or “shared prosperity.” Section Five highlights how other jurisdictions (such as the Province of Saskatchewan) are using multi-year growth strategies to orient their policy agendas towards inclusive growth. The final section concludes with the key takeaways for Canadian policymakers in order to advance a “stretch goal” of higher rates of economic growth and productivity as part of a post-pandemic recovery agenda.

Why Does Economic Growth Matter?

It is worth starting out by understanding economic growth and how it translates into a wider set of measures of economic welfare for individuals and society. Economic growth is not an end; it is a means to the ends of greater opportunity, more and better jobs, and higher living standards.

Gross domestic product (GDP) refers to the total value of goods and services produced over a specific time period. Faster GDP growth reflects higher levels of output and, in turn, an expansion of the overall size of the economy.

A jurisdiction’s level of economic output does not, by any means, tell us everything. It is silent, for instance, on the sources of output or its distribution. One could theorize about an economy that generates economic activity by producing something harmful or that concentrates the gains among a small share of the population.

But, generally speaking, a growing economy is associated with various positive economic and social outcomes. A previous Ontario 360 paper highlighted a wide body of research that shows that higher rates of growth are not only correlated with more investment, innovation, and jobs, but also lower incidences of poverty and higher rates of individual happiness.[7]

Economic growth is a powerful determinant of the economic, political, and social health of a society. It is not just about material well-being either – it can have broader political economy implications that policymakers must be cognizant of in light of growing agitation and polarization in peer jurisdictions.

There has been a tendency to assume that the rise of political polarization and populism in advanced economies is driven by those who have been the so-called “losers” of the Schumpeterian process of “creative destruction.”[8] The underlying idea here is that it is a toxic combination of growth, dynamism, and insecurity that has driven working-class voters to disruptive politics. One might think of the common narrative of runaway automation in general or the so-called “rise of the robots” in particular.[9]

But what if something approximating the opposite is true: the problem is not too much growth and dynamism but too little. People are drawn to a zero-sum form of politics when they become concerned about the economy’s capacity to continue to produce jobs, opportunity, and rising living standards for them.

There is some evidence that economic stagnation has been a contributing factor to the political polarization and zero-sum thinking that has come to shape politics in advanced economies. It is notable for instance that Donald Trump’s populist appeal was most resonant in counties with the weakest income growth and declining populations.[10] There is also a significant “expectations gap” with populist voters who tend to be highly pessimistic about the future economic prospects for them and their families.[11]

The latter point is worth emphasizing: Research shows that pessimism about the future seems to be a key characteristic of populist politics.[12] This is one of the reasons that populism tends to manifest itself in nostalgic messages and themes.[13] It is an appeal to a conception of the past that ostensibly held out more opportunity and hope. Populism should be understood at least in part as a political expression of loss aversion by those who are disproportionately affected by the effects of slowed economic growth and diminished opportunity.

Canadian policymakers would be wrong, by the way, to think that such pessimism is not present in our own country. A recent paper by pollsters Frank Graves and Jeff Smith finds that only 13 per cent of Canadians think future generations will have a better quality of life than Canadians do now.

As the authors put it: “For many, we have reached the end of progress.”

What does this mean for policymakers?

Maybe the so-called “left behinds” have not necessarily been clamouring for more protectionism or welfarism but rather for more growth and opportunity. There is a logic here: one might be prepared to accept higher rates of technology- or trade-induced dislocation – if one were reasonably confident that a growing, dynamic economy were producing more jobs and opportunity for everyone. When the population gets a sense that growth and dynamism are slowing, the consequences of scarcity become ever starker.

This does not mean that people are not also motivated by distributional considerations. There is plenty of evidence that they are concerned about inequality. As we discuss later, it is important that policymakers place a greater emphasis on equity and inclusivity including with respect to growing regional economic disparities.

But they must not neglect economic growth itself. Higher rates of growth are not just a crucial precondition for investment, innovation, and jobs. They may also be in turn a key factor in protecting against polarization, populism, and the zero-sum thinking that underpins them. The antidote to the “end of progress” is a renewed, future-oriented policy commitment to growth, dynamism, and opportunity.

What is Canada’s Recent Economic Performance?

The first step in developing such an agenda is to analyse the data and evidence with respect to Canada’s recent economic performance. It is important to understand how the economy has performed over time and how it compares to peer jurisdictions such as the United States and the other G-7 countries – France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

Canada’s GDP growth

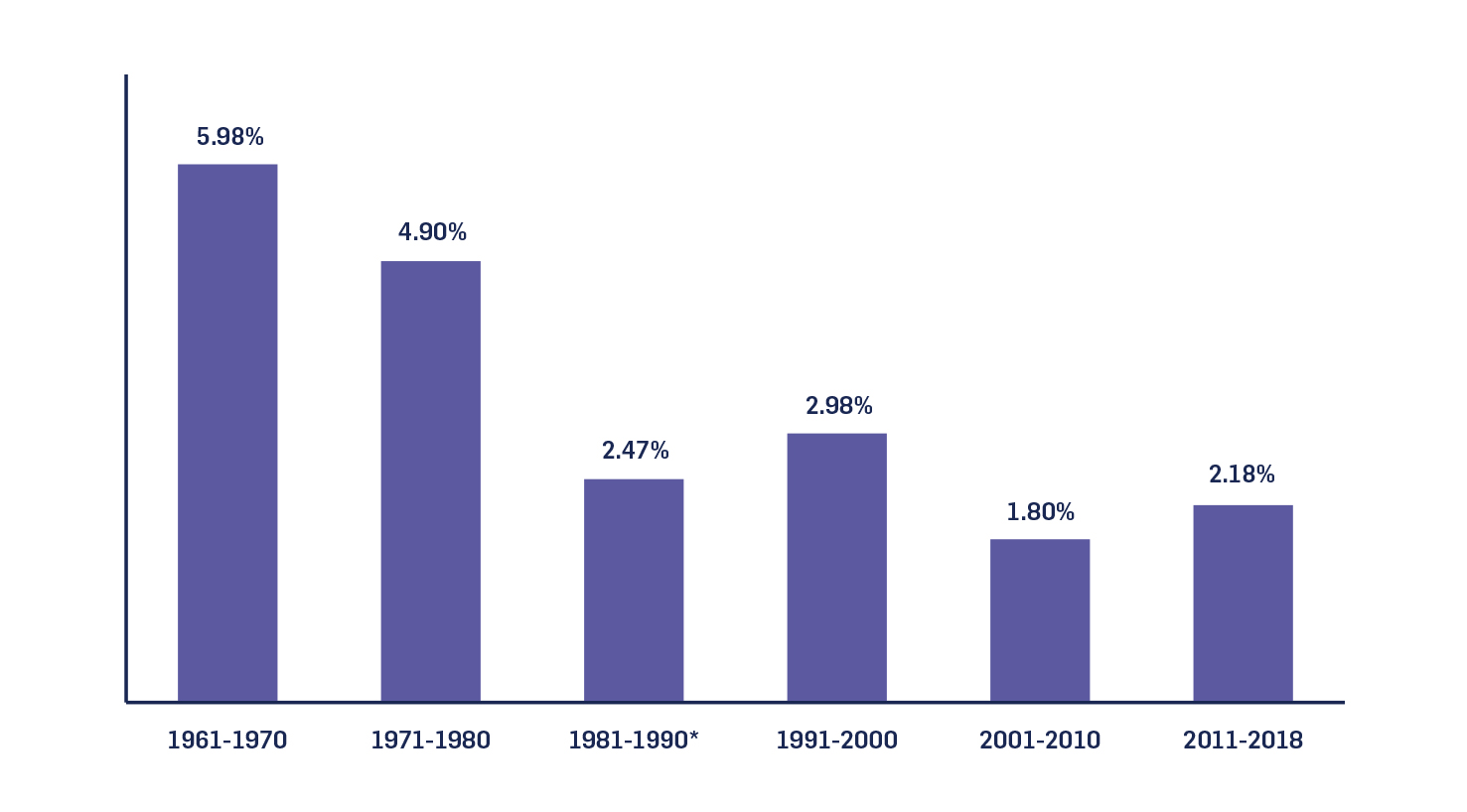

The country’s real GDP growth has generally fallen decade-over-decade since the 1960s. In fact, Canada’s average annual growth per decade has been cut by more than half since the early 1960s. Real GDP growth averaged 6 percent between 1961 and 1970. It fell to 1.8 percent between 2001 and 2010 and only ticked up slightly to an average of 2.2 percent since 2011 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Average Real GDP Growth Per Decade ($2012), Canada

Source: Statistics Canada 2019.[14]

*Asterisk indicates switch from first to second source after 1980.

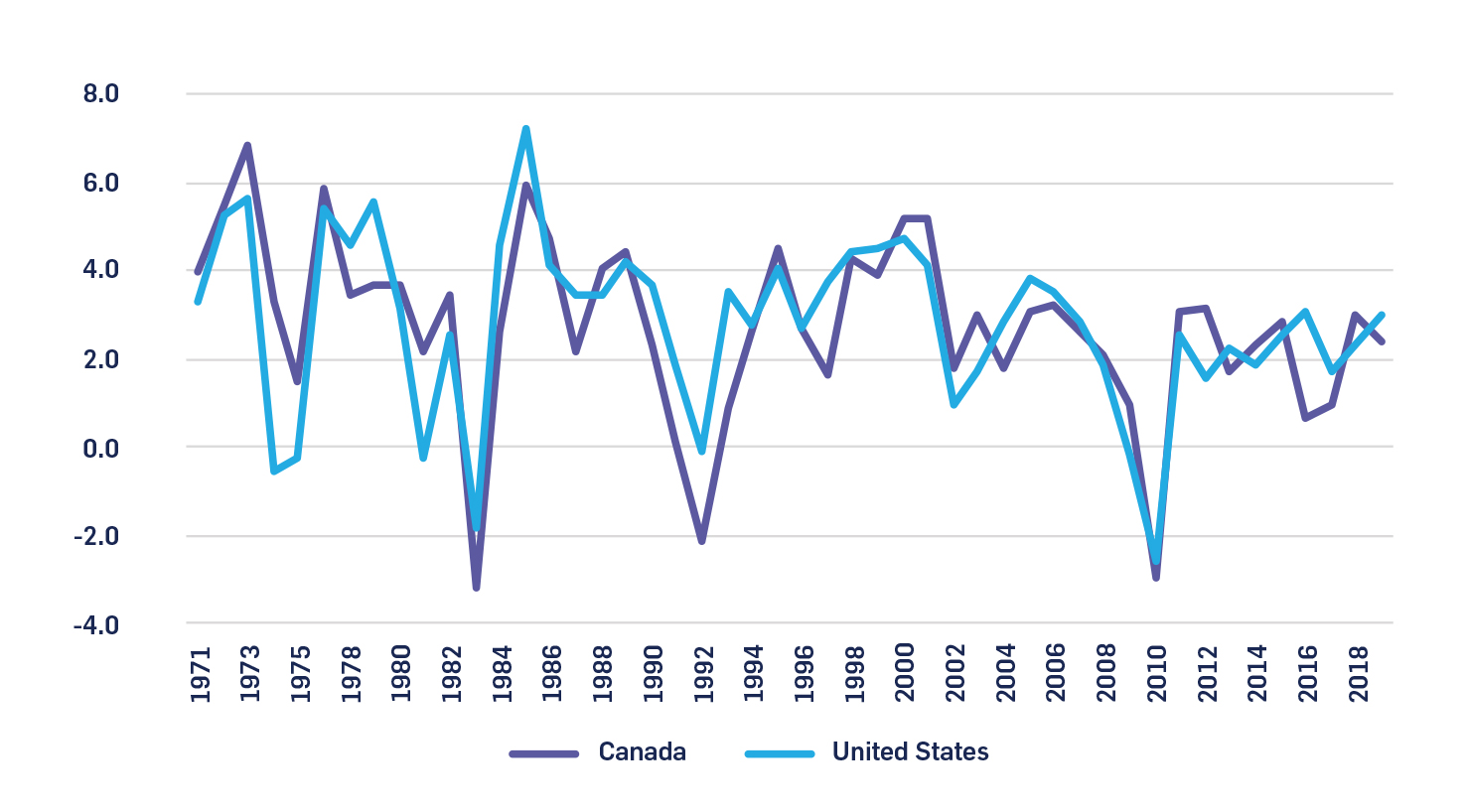

Canada’s experience with slowing growth is not unique. It has been a common phenomenon across peer jurisdictions. The United States, for instance, has followed a similar growth track over the past half century or so (see Figure 2). Its GDP growth rate has steadily fallen over this timeframe and only exceeded 3 percent five times since 2000. By comparison, it exceeded 3 percent thirteen times in the previous 20-year period.

Figure 2: Real GDP Growth, Canada and the United States, 1971 to 2019

Source: OECD, 2020a.[15]

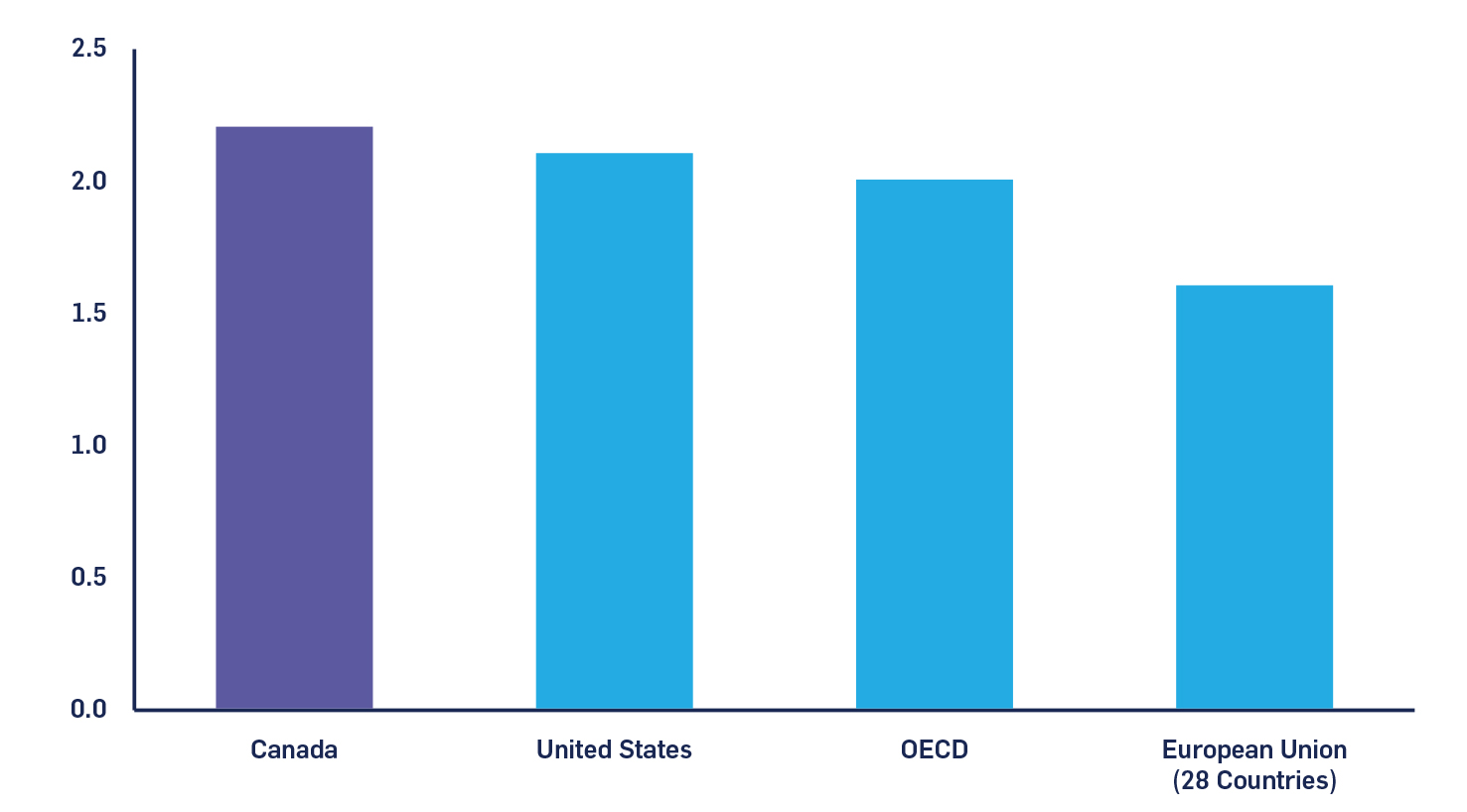

The same goes for the European Union and for the dozens of industrialized countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development generally. In fact, since 2000, Canada’s average annual growth rate of roughly 2 percent compares favourably to each (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Average Real GDP Growth, Canada, United States, European Union and the OECD, 2000 to 2019

Source: OECD, 2020a.[16]

Canada’s productivity growth and living standards

Economic growth can be a bit abstract. It does not in and of itself tell us much about how people live or work, how one jurisdiction compares to others, or even how growth is produced. We need to go a bit further to understand the factors behind Canada’s slowed growth trajectory and the implications for Canadian households.

Broadly speaking, there are two main sources of economic growth: growth in the size of the workforce and growth in productivity (output per hour worked) of that workforce. Either can increase the overall size of the economy but only strong productivity growth (stemming from innovation and technological adoption) can increase GDP per capita (output/ population) and individual incomes. Productivity growth allows people to achieve a higher material standard of living without having to work more hours.

As Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman has put it: “Productivity is not everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything. A country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker.”[17]

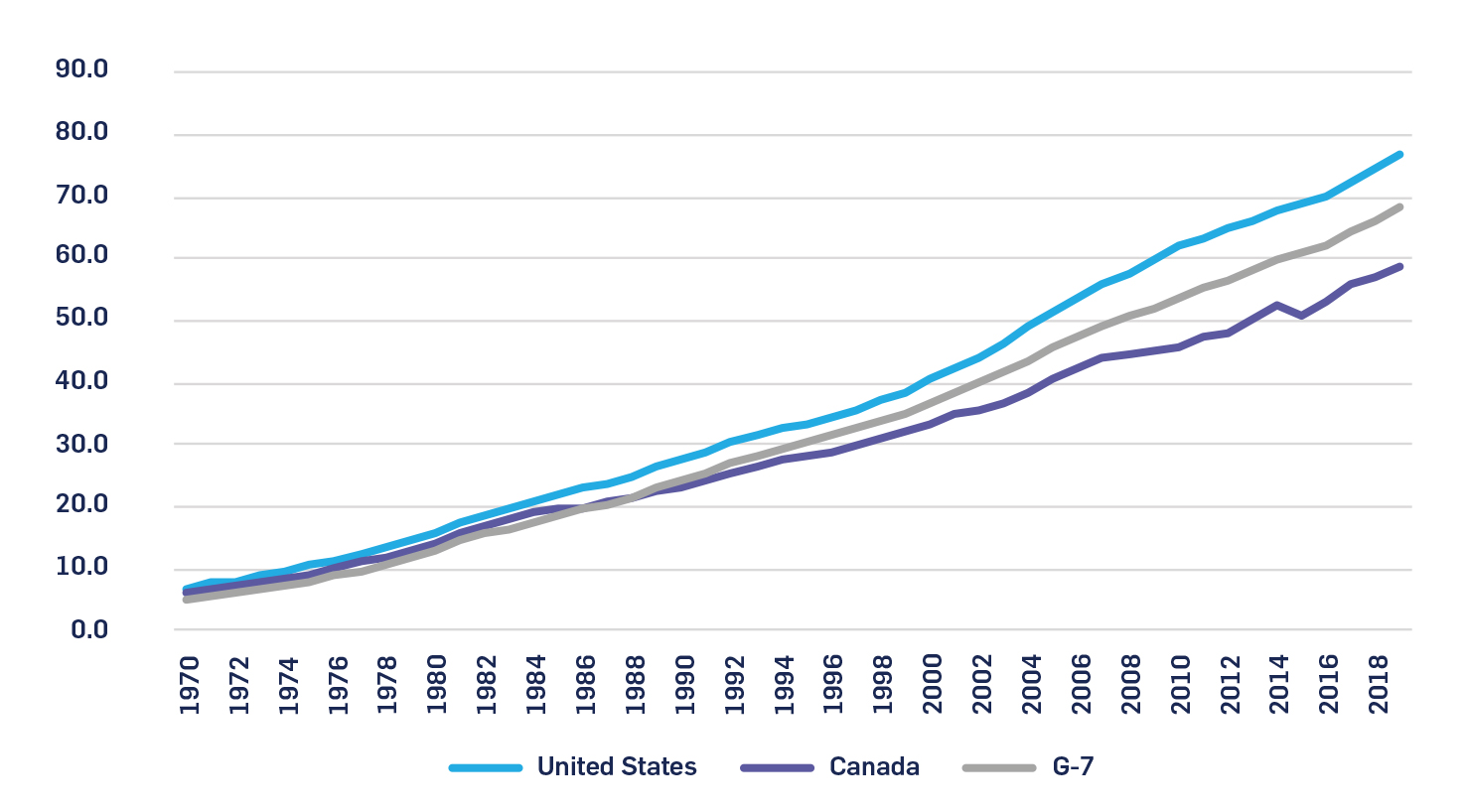

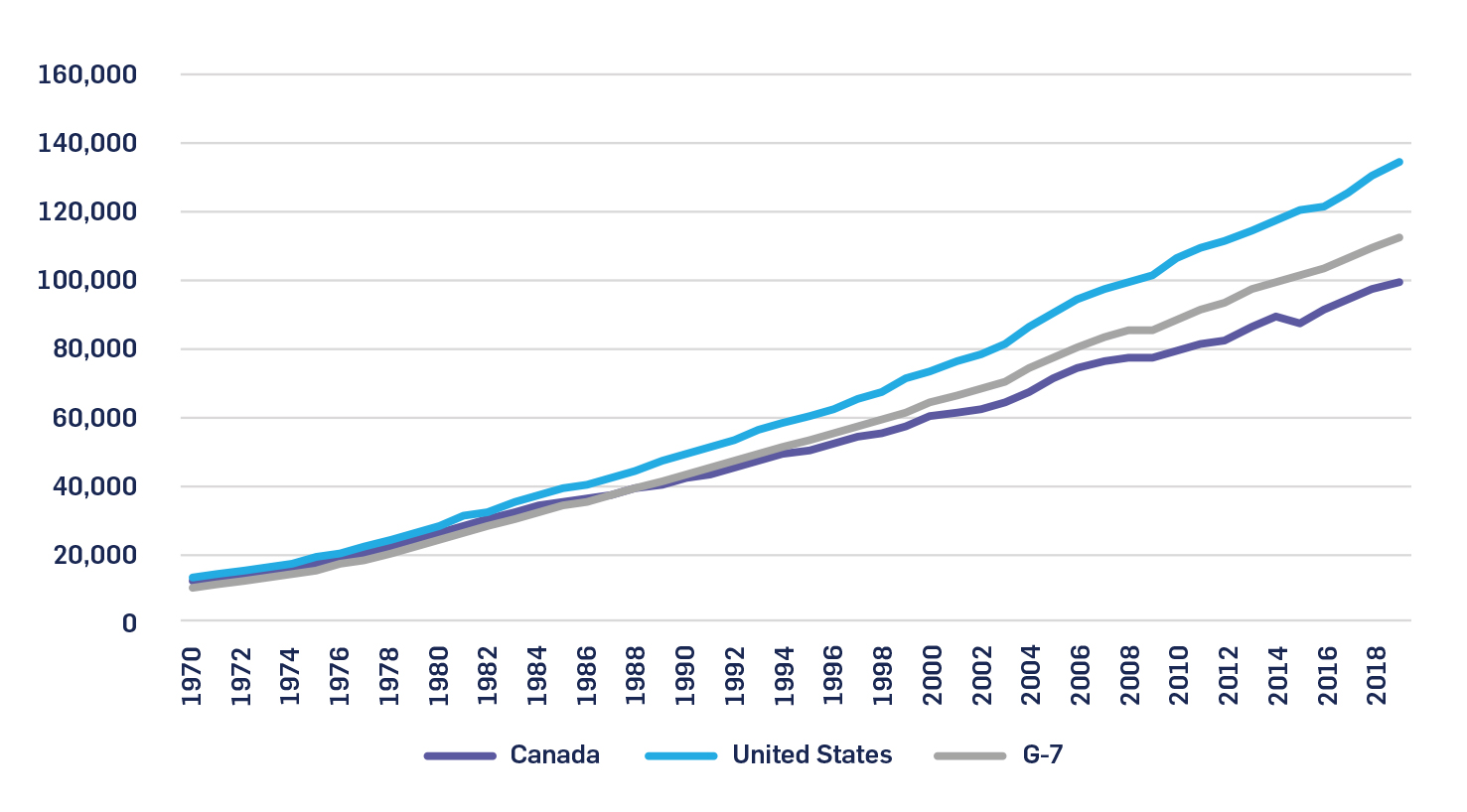

Canada’s productivity performance over the past 50 years has lagged its peer jurisdictions. In 1970, its GDP per hour worked was barely $1 less in output than in the United States and was actually $1 more in output relative to the G-7 average. By 2019, Canada’s GDP per hour worked was $18.10 less than the United States and $9.50 less than the G-7 average (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: GDP Per Hour Worked, Canada, United States and the G-7 (PPP $USD Current Prices), 1970 to 2019

Source: OECD, 2020b.[18]

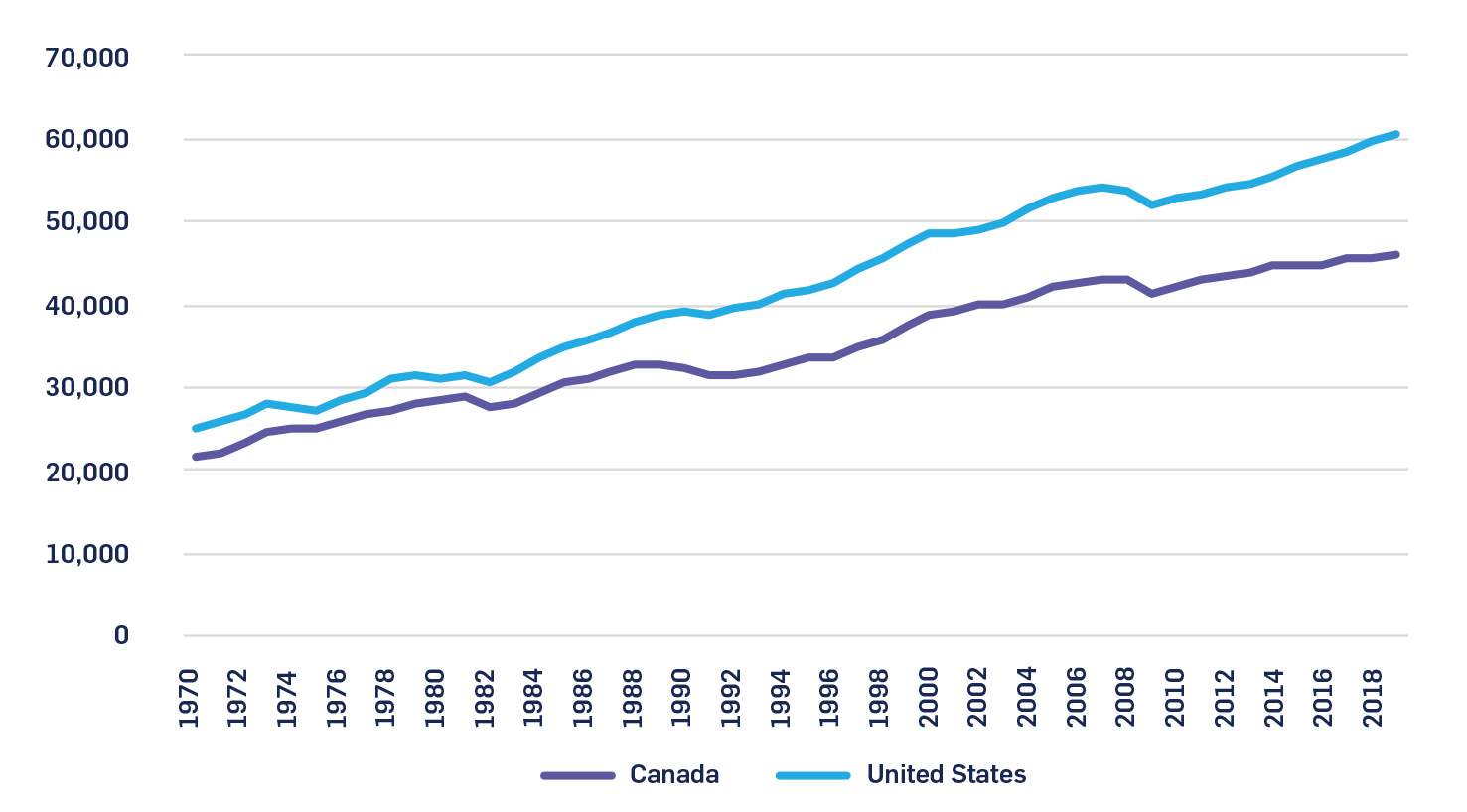

Another way to understand Canada’s poor productivity record is to compare its GDP per person employed. This measure enables us to back out those who are not in the workforce from the analysis. The story is nevertheless the same. In 1970, Canada’s GDP per person employed was $11,678, which was $1,276 less than in the United States and $1,830 more than the G-7 average. By 2019, Canada’s GDP per person employed was $34,631 less than in the United States and $12,971 less than the G-7 average (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: GDP Per Person Employed, Canada, United States and the G-7 (PPP $USD Current Prices), 1970 to 2019

Source: OECD, 2020b.[19]

Canada’s poor productivity record over this period translates into lower relative living standards. GDP per capita (output/ population) enables us to compare Canada’s relative living standards to other jurisdictions, by accounting for sizes of the economy and population and adjusting them to an apples-to-apples basis. It is not a foolproof method of comparing jurisdictions. It does not account, for instance, for income and wealth distribution within a society. But GDP per capita provides a useful basis for comparative analysis of overall wealth and productivity.

The story here is quite striking. Although Canada’s aggregate economic growth has performed relatively well compared to peer jurisdictions, its GDP per capita has grown more slowly.

In 1970, Canada had the second highest GDP per capita of any G-7 member. Its GDP per capita ($21,656) was only $3,601 less than the United States ($25,248). As of 2019, it has fallen to a distant third ($45,850) below Germany ($50,004) and the United States ($60,709). The Canada-U.S. gap is now $14,859 (see Figure 4). In fact, Canada’s GDP per capita has grown less since 1970 than all G-7 countries, except Italy. Germany, Japan, the U.S. and U.K. have all grown by about 12 to 24 percent faster, on average.

Figure 6: Level Of GDP Per Capita, Canada and the United States, (PPP $USD 2015), 1970 to 2019

Source: OECD, 2020c.[20]

It is worth emphasizing this point: Canada’s GDP per capita went from 15-percent lower than the U.S. in 1970 to 25-percent lower in 2019. We are not just poorer, in other words, but we are getting poorer still over time.

A gap of $14,589 is significant when one considers that, according to Statistics Canada, this amount is higher than every Canadian household expenditure except for housing – it is, for instance, 40-percent more than the average household spends on food per year.[21]

The upshot: Canada’s economic growth and in turn its productivity levels and living standards have been slowing for some time in absolute and relative terms. This ought to be a concern for policymakers given that, as we discussed in the previous section, economic growth and productivity are not just determinants of economic outcomes but may also be key contributors to the rise of polarized and populist politics.

What Are The Causes Of Slowed Growth? What Is Secular Stagnation?

The previous section outlined Canada’s recent record on economic growth and productivity. This section aims to place our performance in a broader context to better understand what factors are within the control of federal policymakers and which ones may be less responsive to government policies. It builds on a previous Ontario 360 paper on a Growth Strategy for Ontario.[22]

Canada’s experience is far from unique. It has occurred against a backdrop of a broader debate about “secular stagnation” to describe the sustained period of slower economic growth in advanced economies that has followed the 2008-09 global recession.[23]

The idea of secular stagnation is most prominently associated with former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers. His basic argument is that slow growth in advanced economies is not a product of the typical business cycle but instead reflects deep, structural issues – namely a rise in savings and a corresponding drop in investment– that are immune to traditional supply-side policy responses.[24] His argument is that the slowed economic growth reflects a structural drop in aggregate demand and that only a mix of demand-side policies such as infrastructure spending and tax reform will mitigate these secular challenges.[25]

Other economists such as Robert Gordon agree with the diagnosis of protracted stagnation but may disagree on its causes. Gordon’s work, for instance, points to supply-side challenges rooted in lower productivity rates.[26] His basic argument is that modern society has reached a technological frontier and future growth will be constrained by an inability to break out of this technological stagnation. His work is marked by a pessimism about the role of public policy to reverse the trends of secular stagnation.

The literature points to various other explanations including globalization and the rise of China, the decline of manufacturing, and so on, as possible causes for these trends.[27] But, irrespective of the relative role of these different issues, most economists agree that the effect is that economic growth in advanced economies has slowed and may well continue to face downward pressures.

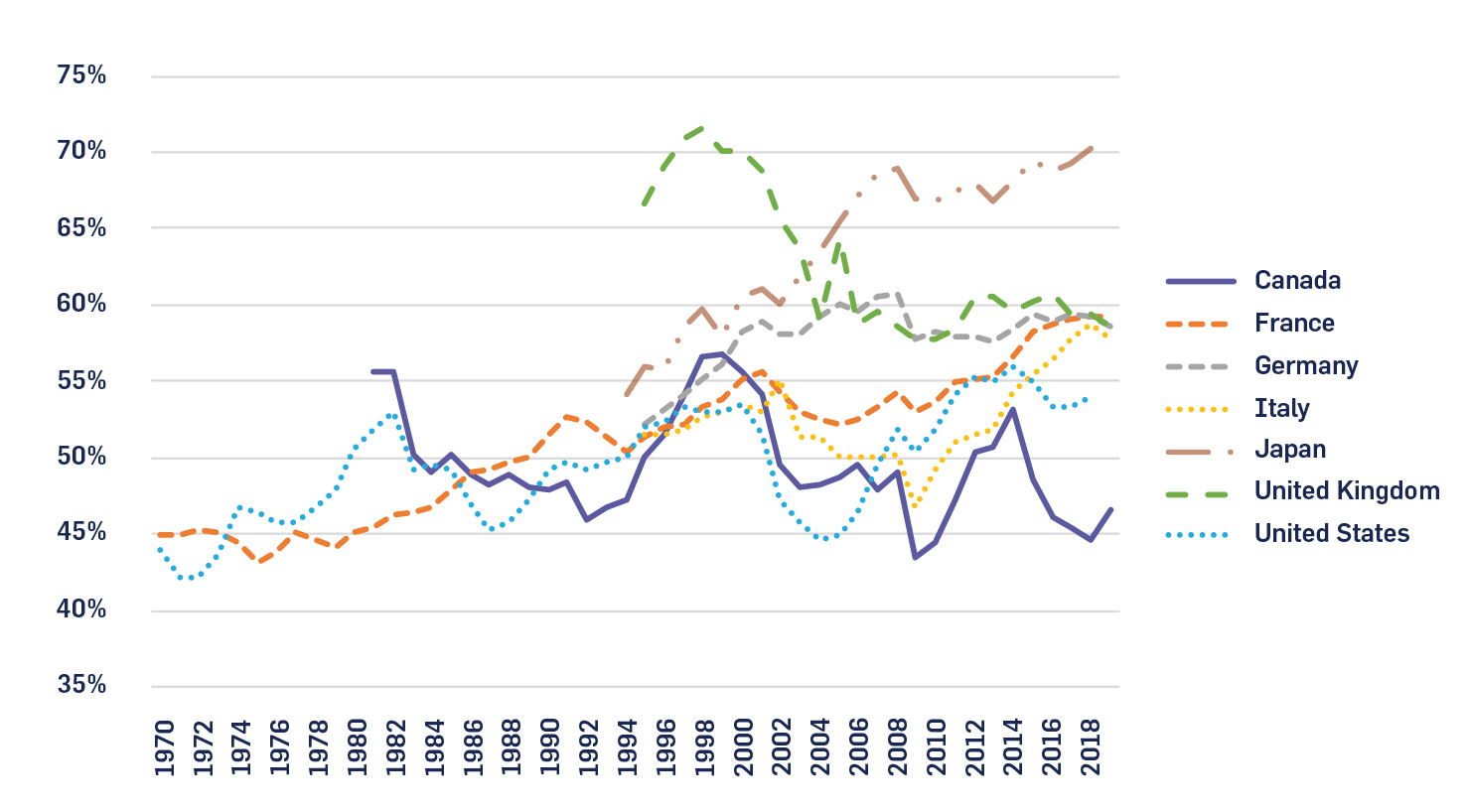

This analysis is important context for Canadian policymakers as they develop the country’s post-COVID recovery plan. They must be cognizant of secular stagnation and its underlying causes. The role played by stagnant or even declining investment is evident here. Take corporate investment for instance. Data from the OECD shows that corporate investment as a share of gross fixed capital formation (which is a common measure to compare investment across jurisdictions) in Canada has fallen to the bottom of the G-7 (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Corporate Investment as a Percentage of Gross Fixed Capital Formation, G-7 Countries, 1970 to 2018

Source: OECD, 2021.[28]

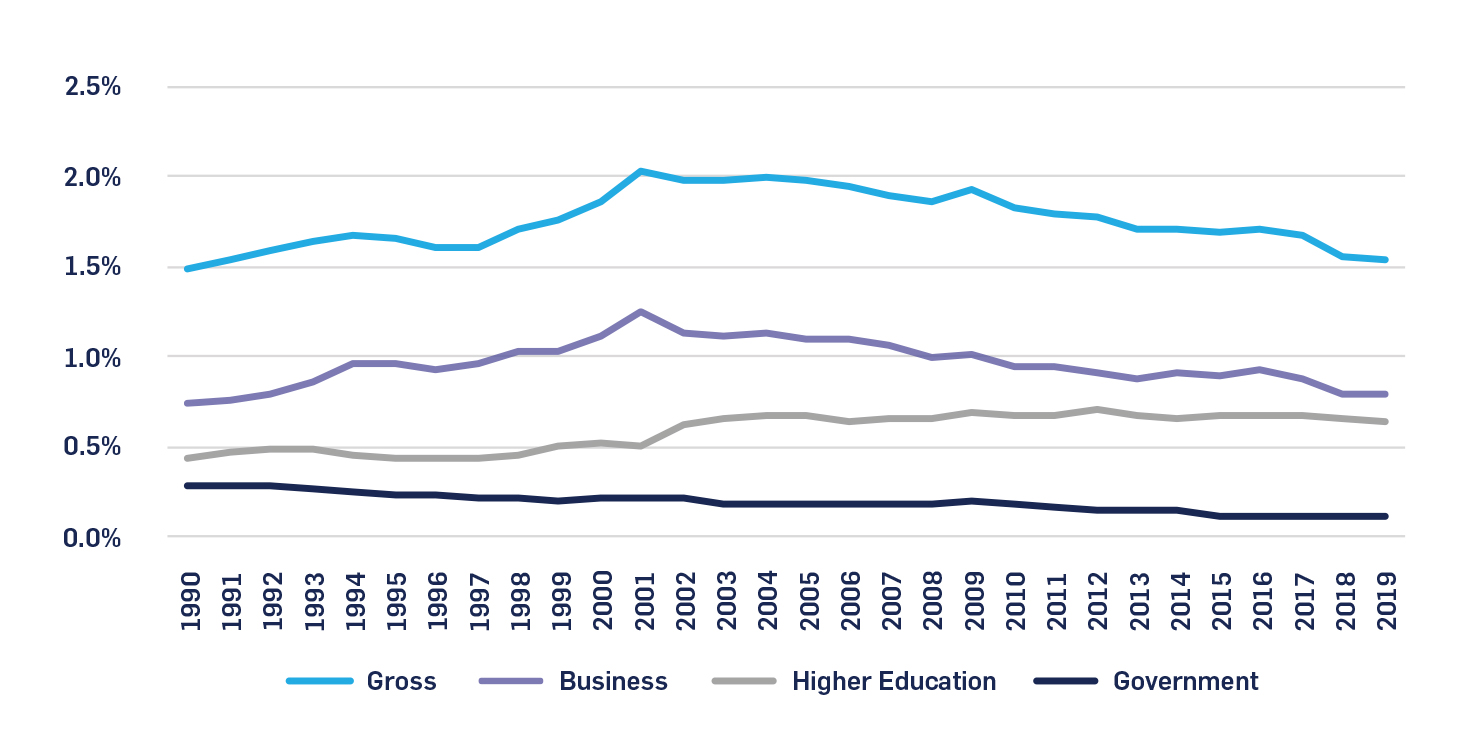

Another area to focus on is gross research and development spending (including by government, businesses, and higher education institutions). Overall R&D spending in Canada has averaged 1.8 percent of GDP since 1990. Business expenditures on R&D have made up more than half the gross amount over this period. Government expenditures have fallen from 0.3 percent of GDP in the early 1990s to just 0.1 percent since 2015 (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Gross Expenditures on Research and Development in Canada, 1990-2019

Source: OECD, 2020d.[29]

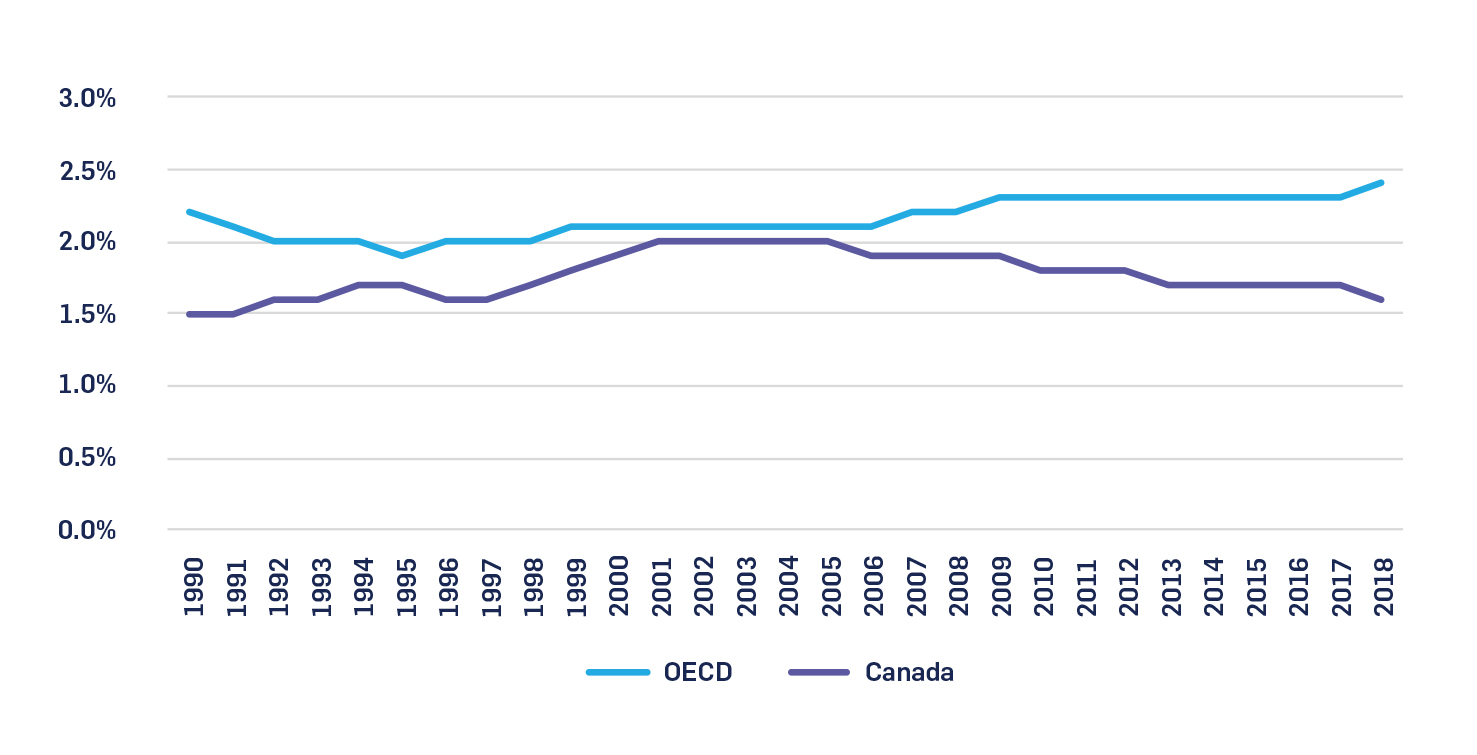

The upshot: Canada’s overall level of R&D spending (including business, government, and higher education) basically matched the OECD average in 2001 but has lagged ever since (see Figure 9). Canada is now investing roughly 1.6 percent of GDP on R&D, while several peer jurisdictions – including Denmark, Finland, Japan and Korea – are close to or exceed 3 percent.

Figure 9: Gross Domestic Spending on Research and Development, OECD Average and Canada, 1990-2018

Source: OECD, 2020f. [30]

This is notable because low R&D spending can contribute to broader economic stagnation. R&D intensity is shown to be a contributing factor for poor innovation, technology adoption, and productivity.[31]

But it is also notable because it is within the realm of public policy. Different policy choices could ostensibly contribute to higher rates of R&D investment and in turn contribute to better economic outcomes. As Tiff Macklem, the current Bank of Canada governor (and a former Ontario 360 author) wrote with co-author Jean Boivin, in 2014: “Better public policies and an improved global financial architecture can unleash significant additional growth.”[32]

There is plenty of room, then, for public policy – including tax and regulatory reform, public infrastructure investments, incentives for private capital investment, greater public support for basic and applied research, and so on – to support higher rates of innovation, productivity, and ultimately economic growth. Even if the impacts are on the margins, marginal differences matter over time.

What Policy Tools Should Be Part Of A Growth Strategy?

If the goal is to boost economic growth, the question of course is: What specific policies can help?

Conventional economic thinking has tended to focus on macroeconomic policy and the overall business climate for investment, innovation, and entrepreneurship. This perspective has mostly conceived of a limited role for government. Public policy has been about setting the macro conditions for market actors rather than drilling into the microeconomic factors influencing industries, firms, and investors.

In practical policy terms, this has placed an emphasis on inflation targeting, sound public finances, a stable monetary policy, and a general skepticism about government intervention in the economy.[33] The basic idea was for policymakers to focus on setting the overall market conditions, but otherwise let market forces and individual actors shape economic outcomes, including the distributional results. Post-market redistributive policies could then minimize the market’s unequal allocation of resources among people and places.

This economic policy paradigm has commonalities across advanced economies. Canada is no exception. It first found expression, at least at the forefront of public policy, in the 1985 Royal Commission on the Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada. It has since come to shape public policy at the federal and provincial levels, including with regard to privatization, trade liberalization, tax reductions, de- regulation, and so on. This overall policy framework has contributed to a range of positive economic and social outcomes. But it has also contributed to higher levels of income inequality and growing geographical disparities.

There are now challenges to this economic paradigm. They were catalyzed by the global financial crisis in 2008-09 and have only accelerated in the context of COVID-19. One concern is the level of income and geographical inequality in our society. Another is the extent to which the rise of intangible capital (including software, data, algorithms, and intellectual property) has shown itself immune to aspects of the old economic paradigm. And another yet is the rise of China and the challenge it poses to the post-Cold War global trading system.

The upshot: there is now new thinking coming to prominence about the goals of economic policy as well as the policy levers relevant for a pro-growth strategy. The main alternative to the current policy paradigm is often defined as “inclusive growth.”

Inclusive growth is defined by the OECD as “economic growth that creates opportunities for all groups of the population and distributes the dividend of shared prosperity.”[34] The basic idea is not to challenge economic growth as an important policy objective but to use market shaping policies to ensure that the benefits of economic growth are more broad-based. There is also growing support for a more active role for governments in shaping – rather than just enabling – technological innovation and adoption in the market economy, particularly in the areas of intangible capital. This trend has increasingly led to a shifting of the policy discussion from the realm of macroeconomics to microeconomics.

The idea of inclusive growth has received significant attention among global leaders and international organizations. Valerie Cerra, division chief at the IMF’s Institute for Capacity Development, for instance, has called inclusive growth the “pivotal economic policy challenge of our time.”[35] UN Secretary-General António Guterres has called on business leaders to support a push for inclusive growth.[36] This has been echoed by former IMF director Christine Lagarde[37] and the leaders of the G20[38], and increasingly put into practice by the OECD[39] and regional organizations like the African Development Bank.[40]

The main effect of this newfound emphasis on economic inclusion is to broaden the set of policies relevant to an economic growth strategy. Traditional policy levers for economic growth are not now obsolete but there is greater interest in new policy areas – such as childcare, public transit, and housing affordability – in supporting higher rates of economic growth and productivity. One might think of this change in terms of augmenting the traditional policy levers for economic growth with a broader set of policy tools to reflect the unique features and characteristics of intangible capital as well as political economy concerns about inclusivity.

A new report from the Canadian Inclusive Economy Initiative, which is an initiative of the Brookfield Institute for Innovation & Entrepreneurship, Ryerson Leadership Lab, First Policy Response, and Springboard Policy, effectively conveys this new, emerging thinking about balancing macro and micro, efficiency and equity, and growth and inclusion.[41] As the report’s authors, Matthew Mendelsohn and Noah Zon put it:

“We need an industrial policy that generates strong economic growth, but recognizes that not all economic growth is created equal. Economic growth that only results in the further concentration of wealth is a failure. Instead, we need to create broadly-shared growth that contributes to the well-being of all Canadians.”

This is a useful framework for thinking about the goals and objective of post- pandemic policies. The emphasis on “broadly-shared growth” – or what may be called “shared prosperity” or, of course, inclusive growth – reflects a recognition that rising inequality among people and places can have harmful economic, political, and social implications.

An inclusive growth agenda can help to push back against these trends. But it is important for policymakers to recognize that in some cases these two objectives – growth and inclusiveness – may conflict and that they will need to think carefully about trade-offs. It is quite possible for instance that a policy emphasis on innovation could lead to a greater concentration of economic activity in urban centres which have pre- existing advantages that position them to better participate in the innovation-based economy. We need to ensure that we emphasize both the adjective – inclusive – and the noun – growth.

But irrespective of where one falls on these possible trade-offs, there is no question that the mix of policies that will be relevant for an inclusive growth agenda will necessarily look different than in the past. A combination of traditional and newer growth-oriented policies will be needed to break out of secular stagnation and accelerate economic growth and productivity. This will require a combination of tax reform, regulatory reform, human capital investments (including university, college, and apprenticeship education), support for R&D and innovation (including a role for government procurement), and high-quality infrastructure (including traditional and digital) as well as well-designed social policies including childcare, income support programming, and skills-training.

Fundamentally, though, it must start with a recognition that our policy choices influence economic growth and productivity, at least on the margins, and so policymakers should have a clear framework for orienting the policy process around these big questions of inclusion, growth, and broad-based opportunity.

A Framework For A Growth Strategy For Canada

It is beyond the scope of this policy paper to outline a comprehensive policy agenda to achieve a “stretch goal” of higher rates of economic growth and productivity in the aftermath of the pandemic. Other Ontario 360 policy papers have put forward specific policy recommendations in relevant areas such as regarding apprenticeships and skilled trades, zoning and land-use policies, regulatory reform, and taxation.[42]

But we can conceive of a broader framework for a growth strategy for Canada – one that enables policymakers to balance trade-offs and orient policymaking to the long-terms goals of growth, dynamism, and progress. Ontario 360’s research shows that other jurisdictions – including nearly half of U.S. states – are doing this. They have started to develop long-term economic growth strategies that draw on a wide range of policy levers.

Such long-term planning is a major gap in the federal government’s policy framework. The government now produces long-term budget projections and various sectoral strategies, but it has not set out a vision for the Canadian economy as a whole, including an understanding of its comparative advantages, how they relate to broader global trends, and how federal policy can accentuate these advantages. A five- or ten-year economic policy framework would help to better situate policy decision- making and bring greater intentionality and coherence across departments.

Such growth strategies elsewhere tend to reflect the unique contexts and particularities of the individual jurisdictions. They also vary with respect to the use of evidence, the robustness of the analysis, and the extent to which they are policy-heavy versus primarily communications documents. But among the best strategies – including the Province of Saskatchewan and the State of Illinois (which we judged to be the best across a range of measures) – there are some common features that are relevant for Canadian policymakers including:

- Five- to ten-year timeframe

- Clear, empirical goals – including private investment, export growth, GDP per capita, household income, job creation, and measures of inclusion

- Analytical assessment of sectors to identify comparative advantages and economy-wide obstacles to better economic performance

- Policy specificities to boost target sectors and address obstacles to better outcomes

- Process for regularized reporting on progress

As noted, the Saskatchewan government’s Growth Plan is a model that federal policymakers should consider adopting at the national level. Its current 10-year plan, which was released in 2019, covers the period up to 2030. It builds on a previous growth plan that was released in 2012 and covered up to 2020.[43]

The plan sets out 30 clear growth-oriented goals that range from the overall economy, such as population size and private capital investment targets, to the sectoral such as agricultural exports and tourism levels. It also sets out 20 actions to achieve these goals. The goals are clear and measurable, such as to increase the value of provincial exports by 50 percent. The actions tend to be a bit more generalized, such as to expand Saskatchewan’s export infrastructure.

But within the various goals there is considerable specificity with respect to policies that the government intends to undertake. As an example, the growth plan highlights tax policy changes – including reinstating sales tax exemptions for exploratory and drilling activity – as part of its plan to achieve the goal of increasing annual uranium sales to $2 billion and potash sales to $9 billion. There are similarly detailed policy commitments throughout the document. In overall terms, it amounts to a comprehensive agenda across the range of policy areas for which the province is responsible.

This exercise of setting clear goals and then identifying policy reforms to meet these goals is highly valuable. It can discipline and focus policymaking, provide greater certainty for businesses and investors, and create an accountability tool for voters.

If there is one weakness with Saskatchewan’s plan, it would benefit from a stronger evidentiary foundation. At times, it reads as if virtually every sector and part of the economy is prioritized. It is also not clear enough how the various goals were set and how ambitious they are relative to historic trends. The original provincial growth plan, by contrast, seems to have better utilized data and evidence on market share, patents, business expenditure on R&D, and other metrics to focus on the most dynamic and productive parts of the provincial economy.

But, nevertheless, the Saskatchewan growth plan is an excellent model for the federal government to emulate. It is clear, measurable, and detailed, and it places economic growth in a broader vision for the province. It outlines various areas – including public investments in mental health services and support for vulnerable citizens, for instance – that are ultimately underwritten by higher rates of economic growth.

What Does All This Mean For Canadian Policymakers?

The key takeaways are:

- High rates of economic growth and productivity are closely correlated to employment, innovation, investment, and higher living standards. Small differences in economic growth compound over time and can have a marked effect on a broad range of economic outcomes.

- There is evidence that economic stagnation has contributed to the political polarization and populism observed in advanced economies in recent years. This interpretation is a bit different than common ones which tend to assume that these political developments are a popular pushback against trade- and technology-induced dislocation by the so-called “losers.” It may indeed be the case that something approximating the opposite is true: The problem is not too much growth and dynamism but too little. People are drawn to a zero-sum form of politics when they become concerned about the economy’s capacity to continue to produce jobs, opportunity, and rising living standards. To the extent to which this interpretation is correct, a greater focus on economic growth can be seen as an antidote to polarization, populism, and the zero-sum thinking that underpins them, so long as it is inclusive in terms of benefits.

- Canada’s rate of economic growth has been falling decade-over-decade for the past fifty years. This sustained drop in economic growth is not unique to Canada. The trend line has been similar in other jurisdictions.

- But the Canada’s comparative economic performance is also underwhelming. Its GDP per capita relative to United States has declined. In 1970, Canada’s GDP per capita was the second highest among G-7 members and only $3,601 less than the U.S. As of 2019, Canada had fallen to a distant third ($45,850) below Germany ($50,004) and the United States ($60,709). The Canada-U.S. gap is now $14,859. In fact, Canada’s GDP per capita has grown less since 1970 than all G-7 countries, except Italy. Germany, Japan, the U.S. and U.K. have all grown by about 12 to 24 percent faster, on average.

- There are various secular forces holding back economic growth in Canada, including: weak productivity growth; low business investment; poor innovation; and aging demographics.

- The Canadian government should dedicate itself to a policy strategy focused on long-term economic growth and higher rates of This is the best means of digging out of the COVID-19 economic crisis in the short-term as well as improving Canadians’ living standards in the long-term.

- Conventional thinking about the role of government in supporting economic growth and productivity has changed. New scholarship and policy thinking place a greater role on a broader range of policies – including childcare, public transit, and housing affordability – in the name of “inclusive growth.” The traditional policy levers for economic growth are being augmented to reflect the unique features and characteristics of intangible capital as well as political economy concerns about inclusivity.

- Several jurisdictions have developed long-term growth strategies rooted in the goal of inclusive growth. Saskatchewan, in particular, has a strong model that Canadian policymakers ought to review closely. Clear, measurable goals and accompanying policy actions can create discipline and focus for policymaking, provide greater certainty for businesses and investors, and create an accountability tool for voters.

Drew Fagan is a professor at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy and a former Ontario deputy minister.

Sean Speer is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy.

Luka Glozic is an independent policy consultant and recent graduate from the Munk School of Public Policy and Global Affairs. He specializes in long-term economic, labour and urban policy issues. He was previously a researcher for the 2019 independent review of the Ontario Workplace Safety Insurance Board. He is currently engaged with research and analysis for the Ontario 360 project.

NOTES

[1] Robert Asselin, “The trillion-dollar question is how federal spending will position the economy for post-pandemic success,” CBC.ca, January 6, 2020.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/opinion/opinion-federal-debt-defict-spending-innovation-1.5841332.

[2] Sean Speer, Drew Fagan, and Luka Glozic, Grow Ontario Stronger: A Framework for the Ontario Government’s Post-Pandemic Recovery Plan, Ontario 360, October 1, 2020. https://wp-a52btu2v90.pairsite.com/policy-papers/grow-ontario-stronger-a-framework-for-the-ontario-governments-post-pandemic-recovery-plan/.

[3] Statistics Canada, “gross domestic product, expenditure-based, provincial and territorial, annual (x 1,000,000),” 2019. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610022201.

[4] World Bank, “GDP growth (annual %) – United States,” date unknown. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=US.

[5] Alexander J. Stewart, Nolan McCarthy, and Joanna J. Bryson, “Polarization under rising inequality and economic decline,” Science Advances, Vol. 6, No. 50, December 2020. https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/6/50/eabd4201.

[6] Shai Davidai and Martino Ongis, “The politics of zero-sum thinking: he relationship between political ideology and the belief that life is a zero-sum game,” Science Advances, Vol. 5, No. 12, December 2019. https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/12/eaay3761.full.

[7] Sean Speer, Drew Fagan, and Luka Glozic, Grow Ontario Stronger: A Framework for the Ontario Government’s Post-Pandemic Recovery Plan, Ontario 360, October 1, 2020. https://wp-a52btu2v90.pairsite.com/policy-papers/grow-ontario-stronger-a-framework-for-the-ontario-governments-post-pandemic-recovery-plan/.

[8] Sean Speer, Forgotten People and Forgotten Places: Canada’s Economic Performance in the Age of Populism, Macdonald-Laurier Institute, August 2019. https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/files/pdf/MLI_Speer_ScopingSeries1_FWeb.pdf.

[9] Martin Ford, Rise of Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future, New York: Basic Book, 2016.

[10] J. Lawrence Broz, Jeffrey Frieden, and Stephen Weymouth, “Populism in place: The economic geography of the globalization backlash,” International Organization, May 2019. https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/jfrieden/files/populism_in_place_v1.3_0.pdf.

[11] Annie Lowrey, “Left economy, right economy,” The Atlantic, June 4, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2018/06/two-economies/561929/.

[12] Wolfgang Fengler, “Why are we so pessimistic?,” Brookings Institution, June 13, 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2019/06/13/why-are-we-so-pessimistic/.

[13] Eefje Steenvoorden, “The appeal of nostalgia: the influence of societal pessimism on support for populist radical right parties,” West European Politics, Vol. 41, Issue 1, 2018. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01402382.2017.1334138.

[14] Statistics Canada, “gross domestic product, expenditure-based, provincial and territorial, annual (x 1,000,000),” 2019. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610022201.

[15] OECD, “GDP, volume – annual growth rates in percentages,” date unknown. https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=60703#.

[16] OECD, “GDP, volume – annual growth rates in percentages,” date unknown. https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=60703#.

[17] Paul R. Krugman, The Age of Diminished Expectations (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994).

[18] OECD, “labour productivity levels – most recent years,” date unknown. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=PDB_LV#.

[19] OECD, “labour productivity levels – most recent years,” date unknown. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=PDB_LV#.

[20] OECD, “level of GDP per capita and productivity,” date unknown. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=PDB_LV.

[21] Statistics Canada, “household spending, Canada, regions and provinces,” Table 11-10-0222-01, date unknown. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110022201.

[22] Sean Speer, Drew Fagan, and Luka Glozic, Grow Ontario Stronger: A Framework for the Ontario Government’s Post-Pandemic Recovery Plan, Ontario 360, October 1, 2020. https://wp-a52btu2v90.pairsite.com/policy-papers/grow-ontario-stronger-a-framework-for-the-ontario-governments-post-pandemic-recovery-plan/.

[23] 23 Jacob Davidson, “This theory may explain why the U.S. economy may never get better,” Time, March 25, 2016. https://time.com/4269733/secular-stagnation-larry-summers/.

[24] Summers, “The age of secular stagnation: What is it and what to do about it,” Foreign Affairs, February 15, 2016. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2016-02-15/age-secular-stagnation.

[25] See for instance Summers, “Accepting the reality of secular stagnation,” Finance & Development (International Monetary Fund) Vol. 57, No. 1, March 2020. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/03/larry-summers-on-secular-stagnation.htm.

[26] Robert J. Gordon, “Secular stagnation: A supply-side view.” American Economic Review, Vol. 105, no. 5, May 1, 2015): 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20151102 ; and Gordon, “Is U.S. economic growth over? Faltering innovation confronts the six headwinds,” National Bureau of Economic Research, August 2012. https://www.nber.org/papers/w18315.pdf.

[27] See for instance Douglas Campbell, “on the causes of secular stagnation: China, relative prices, and the collapse of manufacturing,” VOX EU (Centre for Economic Policy Research), April 15, 2014. https://voxeu.org/article/causes-secular-stagnation.

[28] OECD, “investment (GFCF),” 2021. https://data.oecd.org/gdp/investment-by-sector.htm#indicator-chart.

[29] OECD, “Main science and technology indicators,” 2020. http://www.oecd.org/sti/msti.htm.

[30] OECD, “Gross domestic spending on research and development,” 2020. https://data.oecd.org/rd/gross-domestic-spending-on-r-d.htm.

[31] Council of Canadian Academies, Competing in a Global Innovation Economy: The Current State of R&D in Canada, Expert Panel on the State of Science and Technology and Industrial Research and Development in Canada, 2018. http://new-report.scienceadvice.ca/assets/report/Competing_in_a_Global_Innovation_Economy_FullReport_EN.pdf.

[32] Jean Boivin and Tiff Macklem, “Secular stagnation is not destiny: Faster growth is achievable with better policy,”

[33] Bradford J. De-Long, “The Scary Debate Over Secular Stagnation: Hiccup…or Endgame?,” Milken Institute Review, (2015) https://www.milkenreview.org/articles/the-scary-debate-over-secular-stagnation.

[34] “Opportunities for all: OECD Framework for Policy Action on Inclusive Growth” OECD Policy Brief, May 2018. https://www.oecd.org/inclusive-growth/resources/Opportunities-for-all-OECD-Framework-for-policy-action-on-inclusive-growth.pdf.

[35] Valerie Cerra, “Policies for inclusive growth are essential for our time.” Policy Options, March 25, 2020. https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/march-2020/policies-for-inclusive-growth-are-essential-for-our-time/.

[36] “Progress toward sustainable development is seriously off track,” UN News, November 6, 2019. https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/11/1050831.

[37] Christine Lagarde, “Towards a legacy of inclusion,” The Economist, November 22, 2018. https://worldin2019.economist.com/christinelagardeoninclusivegrowth

[38] “G20 Leaders Communique,” Hangzhou Summit, September 4-5, 2016. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/23621/leaders_communiquehangzhousummit-final.pdf

[39] OECD, “Opportunities for All”, 2018.

[40] “Briefing Note 6: Inclusive Growth Agenda,” African Development Bank Group, April 10, 2012. https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Policy-Documents/FINAL%20Briefing%20Note%206%20Inclusive%20Growth.pdf

[41] Matthew Mendelsohn and Noah Zon, No Country of San Franciscos: An Inclusive Industrial Policy for Canada, Canadian Inclusive Economy Initiative, January 2021.

[42] See the list of Ontario 360 policy papers available here: https://wp-a52btu2v90.pairsite.com/policy-papers/.

[43] Government of Saskatchewan, Saskatchewan’s Plan for Growth: Vision 2020 and Beyond, 2012. http://www.artsalliance.sk.ca/rsu_docs/documents/saskatchewan-plan-for-growth_vision-2020-and-beyond.pdf.